Post by Eaglehawk on Jan 14, 2020 4:23:30 GMT

Southern Cassowary - Casuarius casuarius

Facts

Kingdom Animalia

Phylum Chordata

Class Aves

Order Casuariiformes

Family Casuariidae

Genus Casuarius (1)

Size

Height: 1.3 – 1.7 m

Female weight: up to 60 kg

Male weight: 35 kg

Status

Classified as Vulnerable (VU) on the IUCN Red List 2007.

Description

Cassowaries are large, flightless birds that are related to emus and found only in Australia and New Guinea. The southern cassowary has a glossy black plumage and a bright blue neck, with red colouring at the nape. Two wattles of bare, red coloured skin hang down from the throat. Cassowaries have stout, powerful legs and long feet with 3 toes; the inner toe on each foot has a sharp claw that can reach up to 80 millimetres in length. The name cassowary comes from a Papuan name meaning ‘horned head', referring to the helmet of tough skin born on the crown of the head. This helmet (or casque) slopes backwards and is used to push through vegetation as the cassowary runs through the rainforest with its head down; it also reflects age and dominance. The sexes are similar in appearance although females tend to be larger and heavier. Chicks are striped black and cream; fading to brown after around five months. The adult colouring and casque begin to develop between two and four years of age.

Casque (helmet)

Claws

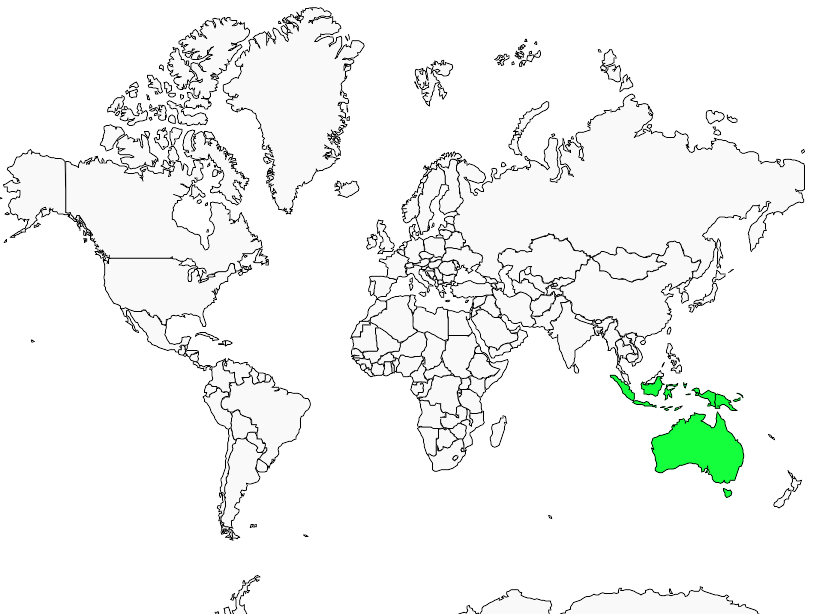

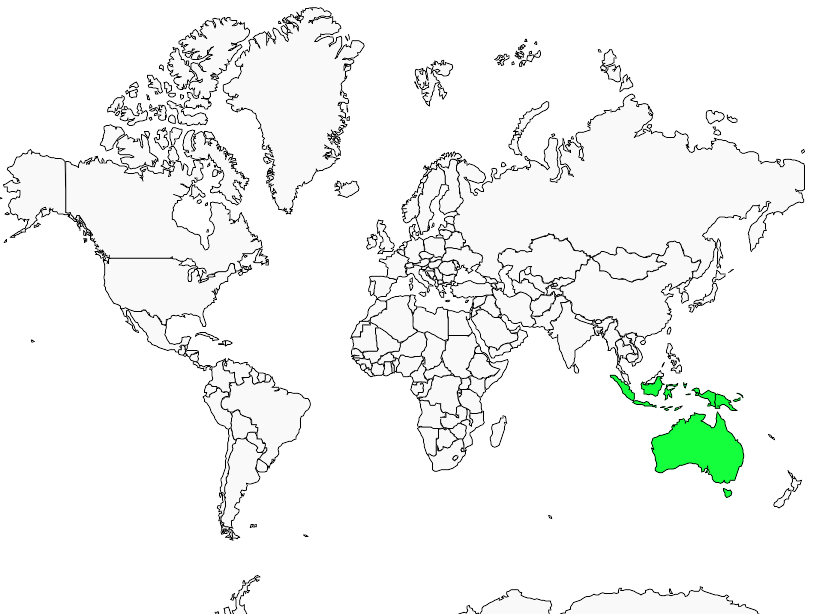

Range

The southern cassowary is found in New Guinea as well as Queensland in northeastern Australia.

Habitat

These birds are rainforest inhabitants, although they are also found in nearby savannah, mangroves and fruit plantations.

Biology

Cassowaries are usually solitary individuals, and males are subordinate to females if they meet. Females may lay several clutches of eggs during the breeding season that runs from June to October. These are laid directly onto the forest floor and the male then takes sole responsibility for their care. The male incubates the eggs for around 50 days, turning the eggs and only leaving his charges in order to drink. He cares for his offspring for up to 16 months, protecting them under his tail if threatened.

Cassowaries fight by kicking out with their legs, they have a fearsome reputation but their diet is composed almost entirely of fruit. These birds are important dispersers of a number of rainforest seeds, ranging far in search of fruiting trees.

Threats

The destruction of rainforest and wet tropical coastal lowland habitat is the most important cause of the decline in population numbers of the southern cassowary. As forest is cleared to make way for agriculture or development, populations become fragmented and isolated, reducing genetic variation and where they may not have access to sufficient food or water sources. Traffic accidents are also important causes of mortality, particularly in Queensland where some areas are becoming increasingly populated. Where cassowaries come into contact with humans, dogs pose a threat to survival, preying particularly on young birds. In New Guinea, cassowaries are important food sources for some communities and are heavily hunted as a result.

Conservation

In Australia most of the remaining habitat of the southern cassowary is now located within protected areas. A recovery plan for the species has been drawn up by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service with the aim of securing and enhancing the status of the southern cassowary in Australia through integrated conservation initiatives. In New Guinea, further data on population numbers is required and hunting restrictions may need to be imposed. This awesome bird belongs to an ancient lineage and is one of the most striking of the flightless birds; its conservation has important cultural and ecological significance.

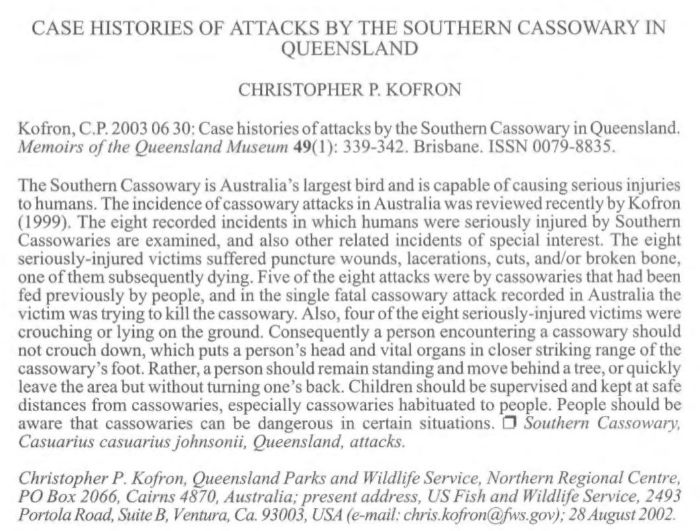

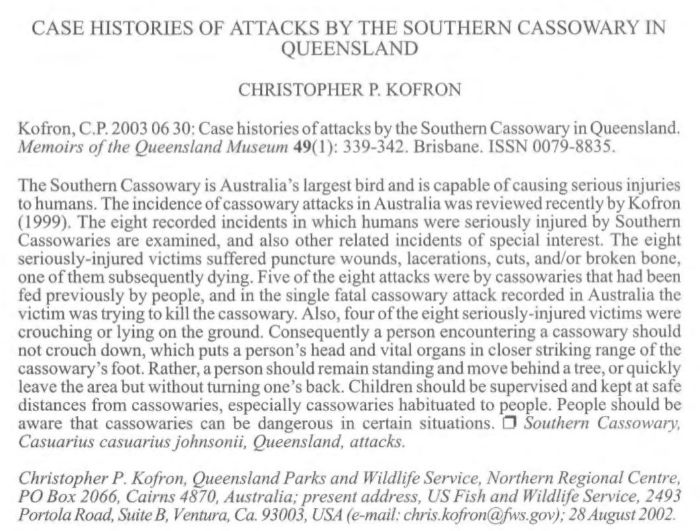

Case histories of attacks by the Southern Cassowary in Queensland

www.qm.qld.gov.au/~/media/Documents/QM/...1/n49-1-kofron.pdf

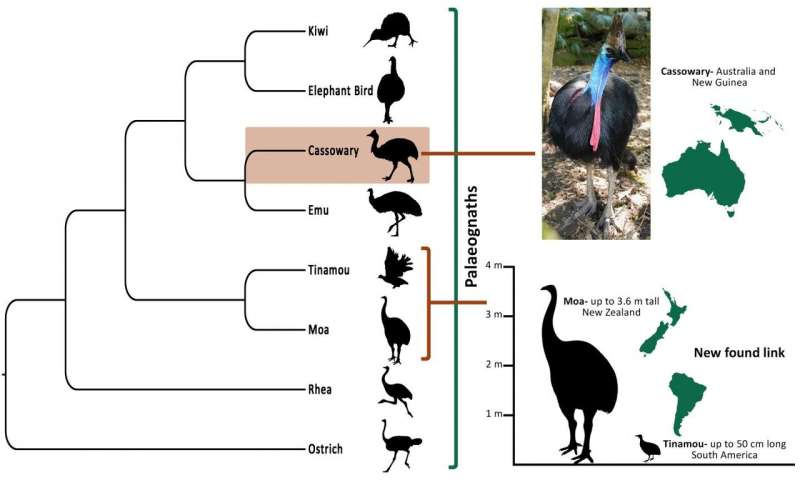

Inside story on cassowary evolution

by Flinders University

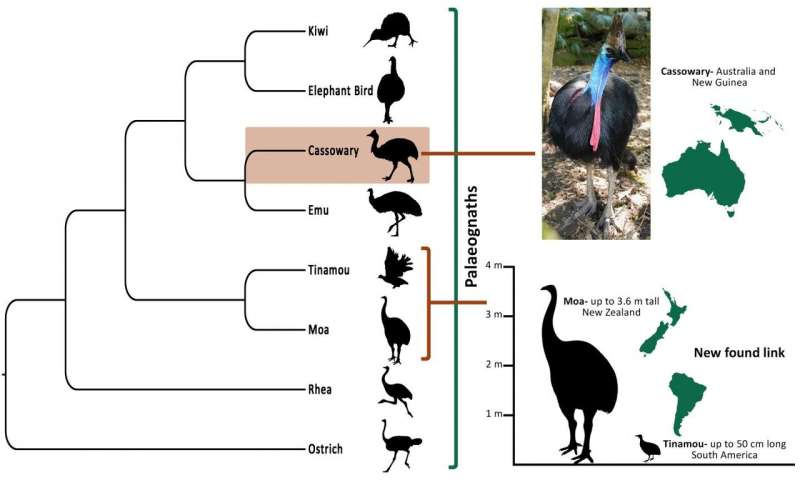

The current relationships between palaeognaths (the cassowary and close relatives) as determined from genetic data, with now, further support from morphological data. Credit: Flinders University

One of the largest living birds, the Southern Cassowary, has a simple throat structure similar to the fellow Australian emu. Now new research confirms a common link between the cassowary and small flighted South American tinamou—and even the extinct large New Zealand moa.

The cassowary, a colourful yet solitary big bird from far north Queensland and Papua New Guinea, has been studied for centuries but now Flinders University researchers have studied the internal features of its throat to confirm a 'missing link' in its evolution.

Focusing on the syrinx, hyoid and larynx, which are used for breathing, eating and vocalising, advanced technologies and 3-D digital modelling techniques including non-invasive CT scanning have led Flinders scientist to fill in some gaps in the evolution of the Australian birds and their relations in more distant places.

The results have been published in the international journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

"What surprised the authors was that despite the vast variation in locations of the cassowaries and other primitive living birds, the extinct moa and South American tinamou are very similar," says lead author Phoebe McInerney.

"Scanning lets us see details that we wouldn't be able to otherwise, including the shapes of the internal structures, without causing damage to them," she says.

The relationships between palaeognaths the cassowary and close relatives, as determined from genetic data, has now been supported by morphological data. Credit: Flinders University

Usually hidden in dense Australian and PNG rainforest, the colourful cassowary is part of the palaeognaths group of primitive birds, which includes the largest bird in the world, the African ostrich, the emu, moa, tinamou, kiwi, rhea and extinct Madagascan elephant bird.

The latest study confirms scepticism from separate recent DNA analysis pointing to the close relationship between the cassowary, moa and tinamou—with the large, flightless moa a stark contrast to the small, flighted partridge-like tinamou.

"The unexpected family tree for primitive birds based on genomic evidence is looking more and more convincing," says co-author Professor Michael Lee, from Flinders University and the South Australian Museum.

"The morphology of the often-overlooked larynx has shown to be far superior than the other anatomical traits biologists previously used to infer evolutionary relationships, such as wings or leg sizes," says another co-author Associate Professor Trevor Worthy.

The researchers conclude that the study emphasises the importance of small organs and other internal details often ignored in the past when studying evolutionary relationships among birds.

phys.org/news/2020-01-story-cassowary-evolution.html

Journal Reference:

Phoebe L. McInerney et al, The phylogenetic significance of the morphology of the syrinx, hyoid and larynx, of the southern cassowary, Casuarius casuarius (Aves, Palaeognathae), BMC Evolutionary Biology (2019). DOI: 10.1186/s12862-019-1544-7

Abstract

Background

Palaeognathae is a basal clade within Aves and include the large and flightless ratites and the smaller, volant tinamous. Although much research has been conducted on various aspects of palaeognath morphology, ecology, and evolutionary history, there are still areas which require investigation. This study aimed to fill gaps in our knowledge of the Southern Cassowary, Casuarius casuarius, for which information on the skeletal systems of the syrinx, hyoid and larynx is lacking - despite these structures having been recognised as performing key functional roles associated with vocalisation, respiration and feeding. Previous research into the syrinx and hyoid have also indicated these structures to be valuable for determining evolutionary relationships among neognath taxa, and thus suggest they would also be informative for palaeognath phylogenetic analyses, which still exhibits strong conflict between morphological and molecular trees.

Results

The morphology of the syrinx, hyoid and larynx of C. casuarius is described from CT scans. The syrinx is of the simple tracheo-bronchial syrinx type, lacking specialised elements such as the pessulus; the hyoid is relatively short with longer ceratobranchials compared to epibranchials; and the larynx is comprised of entirely cartilaginous, standard avian anatomical elements including a concave, basin-like cricoid and fused cricoid wings. As in the larynx, both the syrinx and hyoid lack ossification and all three structures were most similar to Dromaius. We documented substantial variation across palaeognaths in the skeletal character states of the syrinx, hyoid, and larynx, using both the literature and novel observations (e.g. of C. casuarius). Notably, new synapomorphies linking Dinornithiformes and Tinamidae are identified, consistent with the molecular evidence for this clade. These shared morphological character traits include the ossification of the cricoid and arytenoid cartilages, and an additional cranial character, the articulation between the maxillary process of the nasal and the maxilla.

Conclusion

Syrinx, hyoid and larynx characters of palaeognaths display greater concordance with molecular trees than do other morphological traits. These structures might therefore be less prone to homoplasy related to flightlessness and gigantism, compared to typical morphological traits emphasised in previous phylogenetic studies.

bmcevolbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12862-019-1544-7

Facts

Kingdom Animalia

Phylum Chordata

Class Aves

Order Casuariiformes

Family Casuariidae

Genus Casuarius (1)

Size

Height: 1.3 – 1.7 m

Female weight: up to 60 kg

Male weight: 35 kg

Status

Classified as Vulnerable (VU) on the IUCN Red List 2007.

Description

Cassowaries are large, flightless birds that are related to emus and found only in Australia and New Guinea. The southern cassowary has a glossy black plumage and a bright blue neck, with red colouring at the nape. Two wattles of bare, red coloured skin hang down from the throat. Cassowaries have stout, powerful legs and long feet with 3 toes; the inner toe on each foot has a sharp claw that can reach up to 80 millimetres in length. The name cassowary comes from a Papuan name meaning ‘horned head', referring to the helmet of tough skin born on the crown of the head. This helmet (or casque) slopes backwards and is used to push through vegetation as the cassowary runs through the rainforest with its head down; it also reflects age and dominance. The sexes are similar in appearance although females tend to be larger and heavier. Chicks are striped black and cream; fading to brown after around five months. The adult colouring and casque begin to develop between two and four years of age.

Casque (helmet)

Claws

Range

The southern cassowary is found in New Guinea as well as Queensland in northeastern Australia.

Habitat

These birds are rainforest inhabitants, although they are also found in nearby savannah, mangroves and fruit plantations.

Biology

Cassowaries are usually solitary individuals, and males are subordinate to females if they meet. Females may lay several clutches of eggs during the breeding season that runs from June to October. These are laid directly onto the forest floor and the male then takes sole responsibility for their care. The male incubates the eggs for around 50 days, turning the eggs and only leaving his charges in order to drink. He cares for his offspring for up to 16 months, protecting them under his tail if threatened.

Cassowaries fight by kicking out with their legs, they have a fearsome reputation but their diet is composed almost entirely of fruit. These birds are important dispersers of a number of rainforest seeds, ranging far in search of fruiting trees.

Threats

The destruction of rainforest and wet tropical coastal lowland habitat is the most important cause of the decline in population numbers of the southern cassowary. As forest is cleared to make way for agriculture or development, populations become fragmented and isolated, reducing genetic variation and where they may not have access to sufficient food or water sources. Traffic accidents are also important causes of mortality, particularly in Queensland where some areas are becoming increasingly populated. Where cassowaries come into contact with humans, dogs pose a threat to survival, preying particularly on young birds. In New Guinea, cassowaries are important food sources for some communities and are heavily hunted as a result.

Conservation

In Australia most of the remaining habitat of the southern cassowary is now located within protected areas. A recovery plan for the species has been drawn up by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service with the aim of securing and enhancing the status of the southern cassowary in Australia through integrated conservation initiatives. In New Guinea, further data on population numbers is required and hunting restrictions may need to be imposed. This awesome bird belongs to an ancient lineage and is one of the most striking of the flightless birds; its conservation has important cultural and ecological significance.

Case histories of attacks by the Southern Cassowary in Queensland

www.qm.qld.gov.au/~/media/Documents/QM/...1/n49-1-kofron.pdf

Inside story on cassowary evolution

by Flinders University

The current relationships between palaeognaths (the cassowary and close relatives) as determined from genetic data, with now, further support from morphological data. Credit: Flinders University

One of the largest living birds, the Southern Cassowary, has a simple throat structure similar to the fellow Australian emu. Now new research confirms a common link between the cassowary and small flighted South American tinamou—and even the extinct large New Zealand moa.

The cassowary, a colourful yet solitary big bird from far north Queensland and Papua New Guinea, has been studied for centuries but now Flinders University researchers have studied the internal features of its throat to confirm a 'missing link' in its evolution.

Focusing on the syrinx, hyoid and larynx, which are used for breathing, eating and vocalising, advanced technologies and 3-D digital modelling techniques including non-invasive CT scanning have led Flinders scientist to fill in some gaps in the evolution of the Australian birds and their relations in more distant places.

The results have been published in the international journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

"What surprised the authors was that despite the vast variation in locations of the cassowaries and other primitive living birds, the extinct moa and South American tinamou are very similar," says lead author Phoebe McInerney.

"Scanning lets us see details that we wouldn't be able to otherwise, including the shapes of the internal structures, without causing damage to them," she says.

The relationships between palaeognaths the cassowary and close relatives, as determined from genetic data, has now been supported by morphological data. Credit: Flinders University

Usually hidden in dense Australian and PNG rainforest, the colourful cassowary is part of the palaeognaths group of primitive birds, which includes the largest bird in the world, the African ostrich, the emu, moa, tinamou, kiwi, rhea and extinct Madagascan elephant bird.

The latest study confirms scepticism from separate recent DNA analysis pointing to the close relationship between the cassowary, moa and tinamou—with the large, flightless moa a stark contrast to the small, flighted partridge-like tinamou.

"The unexpected family tree for primitive birds based on genomic evidence is looking more and more convincing," says co-author Professor Michael Lee, from Flinders University and the South Australian Museum.

"The morphology of the often-overlooked larynx has shown to be far superior than the other anatomical traits biologists previously used to infer evolutionary relationships, such as wings or leg sizes," says another co-author Associate Professor Trevor Worthy.

The researchers conclude that the study emphasises the importance of small organs and other internal details often ignored in the past when studying evolutionary relationships among birds.

phys.org/news/2020-01-story-cassowary-evolution.html

Journal Reference:

Phoebe L. McInerney et al, The phylogenetic significance of the morphology of the syrinx, hyoid and larynx, of the southern cassowary, Casuarius casuarius (Aves, Palaeognathae), BMC Evolutionary Biology (2019). DOI: 10.1186/s12862-019-1544-7

Abstract

Background

Palaeognathae is a basal clade within Aves and include the large and flightless ratites and the smaller, volant tinamous. Although much research has been conducted on various aspects of palaeognath morphology, ecology, and evolutionary history, there are still areas which require investigation. This study aimed to fill gaps in our knowledge of the Southern Cassowary, Casuarius casuarius, for which information on the skeletal systems of the syrinx, hyoid and larynx is lacking - despite these structures having been recognised as performing key functional roles associated with vocalisation, respiration and feeding. Previous research into the syrinx and hyoid have also indicated these structures to be valuable for determining evolutionary relationships among neognath taxa, and thus suggest they would also be informative for palaeognath phylogenetic analyses, which still exhibits strong conflict between morphological and molecular trees.

Results

The morphology of the syrinx, hyoid and larynx of C. casuarius is described from CT scans. The syrinx is of the simple tracheo-bronchial syrinx type, lacking specialised elements such as the pessulus; the hyoid is relatively short with longer ceratobranchials compared to epibranchials; and the larynx is comprised of entirely cartilaginous, standard avian anatomical elements including a concave, basin-like cricoid and fused cricoid wings. As in the larynx, both the syrinx and hyoid lack ossification and all three structures were most similar to Dromaius. We documented substantial variation across palaeognaths in the skeletal character states of the syrinx, hyoid, and larynx, using both the literature and novel observations (e.g. of C. casuarius). Notably, new synapomorphies linking Dinornithiformes and Tinamidae are identified, consistent with the molecular evidence for this clade. These shared morphological character traits include the ossification of the cricoid and arytenoid cartilages, and an additional cranial character, the articulation between the maxillary process of the nasal and the maxilla.

Conclusion

Syrinx, hyoid and larynx characters of palaeognaths display greater concordance with molecular trees than do other morphological traits. These structures might therefore be less prone to homoplasy related to flightlessness and gigantism, compared to typical morphological traits emphasised in previous phylogenetic studies.

bmcevolbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12862-019-1544-7