Post by Eaglehawk on Dec 21, 2019 3:24:03 GMT

Peregrine Falcon - Falco peregrinus

The Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), sometimes formerly known in North America as Duck Hawk, is a medium-sized falcon about the size of a large crow: 380-530 millimetres (15-21 in) long. The English and scientific species names mean "wandering falcon", and refer to the fact that some populations are migratory. It has a wingspan of about 1 meter (40 in). Males weigh 570-710 grams; the noticeably larger females weigh 910-1190 grams.

The Peregrine Falcon is the fastest creature on the planet in its hunting dive, the stoop, in which it soars to a great height, then dives steeply at speeds in excess of 300 km/h (185mph) into either wing of its prey, so as not to harm itself on impact. Although not self-propelled speeds, due to the fact that the falcon gathers the momentum and controls its dive, capture (if any) and landing in its own right, technically there is no faster animal. The fastest speed recorded is 390 km/h (242.3mph).

The fledglings practice the roll and the pumping of the wings before they master the actual stoop.

Range, habitat and subspecies

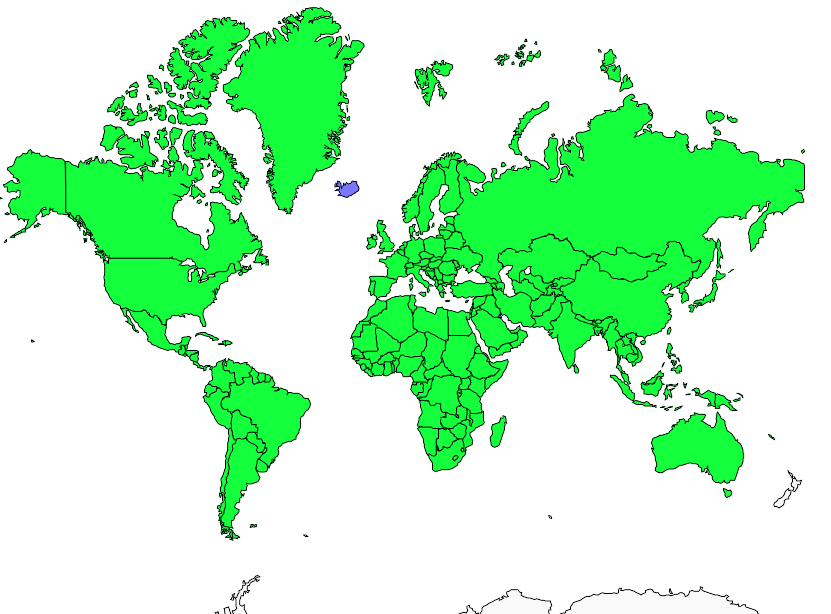

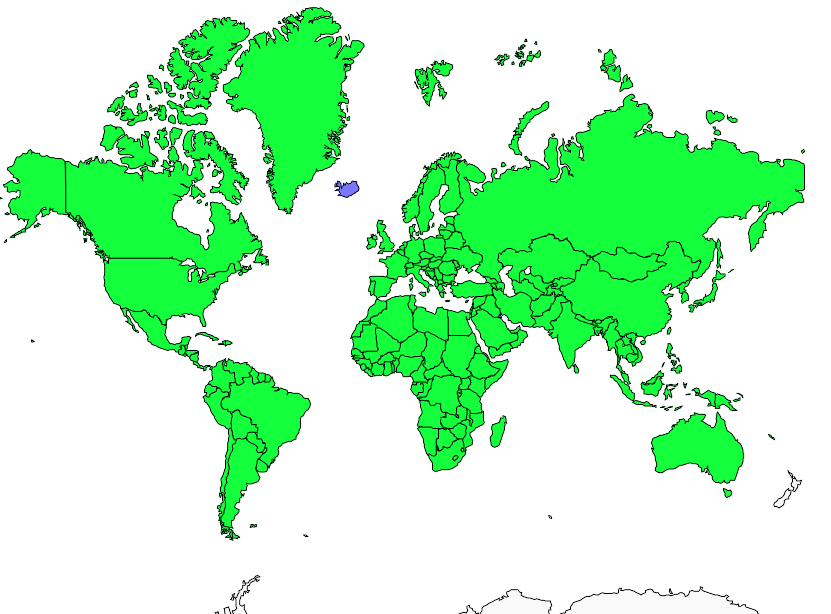

Peregrine Falcons live mostly along mountain ranges, river valleys, and coastlines and increasingly, in cities. They are widespread throughout the entire world and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

There are many subspecies of Peregrine Falcon, including:

Peregrines in mild-winter regions are usually permanent residents, and some birds, especially adult males, will remain on the breeding territory. However, the Arctic subspecies migrate; tundrius birds from Alaska, northern Canada and Greenland migrate to Central and South America, and all calidus birds from northern Eurasia move further south or to coasts in winter.

Australian Peregrine Falcons are non-migratory, and their breeding season is from July to November each year.

Behaviour

Peregrine Falcons feed almost exclusively on birds, such as doves, waterfowl and songbirds, but occasionally they hunt small mammals, including bats, rats, voles and rabbits. Insects and reptiles make up a relatively small proportion of their diet. On the other hand, a growing number of city-dwelling Falcons find that feral pigeons and Common Starlings provide plenty of food. Peregrine Falcon also eat thier own chicks when starving.

Peregrine Falcons breed at approximately two or three years of age. They mate for life and return to the same nesting spot annually. Their courtship flight includes a mix of aerial acrobatics, precise spirals, and steep dives. The male passes prey it has caught to the female in midair. To make this possible, the female actually flies upside-down to receive the food from the male's talons. Females lay an average clutch of three or four eggs in a scrape, normally on cliff edges or, increasingly, on tall buildings or bridges. They occasionally nest in tree hollows or in the disused nest of other large birds.

The laying date varies according to locality, but is generally:

from February to March (in the Northern Hemisphere)

from July to August (in the Southern Hemisphere)

The females incubate the eggs for twenty-nine to thirty-two days at which point the eggs hatch. While the males also sometimes help with the incubation of the eggs, they only do so occasionally and for short periods.

Thirty-five to forty-two days after hatching, the chicks will fledge, but they tend to remain dependent on their parents for a further two months. The tiercel, or male, provides most of the food for himself, the female, and the chicks; the falcon, or female, stays and watches the young.

The average life span of a Peregrine Falcon is approximately eight to ten years, although some have been recorded to live until slightly more than twenty years of age.

Threats

The Peregrine Falcon became endangered because of the overuse of pesticides, during the 1950s and 1960s. Pesticide build-up interfered with reproduction, thinning eggshells and severely restricting the ability of birds to reproduce. The DDT buildup in the falcon's fat tissues would result in less calcium in the eggshells, leading to flimsier, more fragile eggs. In several parts of the world, this species was wiped out by pesticides.

Peregrine eggs and chicks are often targeted by thieves and collectors, so it is normal practice not to publicise unprotected nest locations.

Recovery efforts

Wildlife services around the world organized Peregrine Falcon recovery teams to breed them in captivity.

The birds were fed through a chute, so they could not see the human trainers. Then, when they were old enough, the box was opened. This allowed the bird to test its wings. As the bird got stronger, the food was reduced because the bird could hunt its own food. This procedure is called hacking. To release a captive-bred falcon, the bird was placed in a special box at the top of a tower or cliff ledge.

Worldwide recovery efforts have been remarkably successful. In the United States, the banning of DDT eventually allowed released birds to breed successfully. There are now dozens of breeding pairs of Peregrine Falcons in the northeastern USA and Canada.

Many have settled in large cities, including London Ontario and Derby, where they nest on cathedrals, skyscraper window ledges, and the towers of suspension bridges. About 18 pairs nested in New York City in 2005.

These structures typically closely resemble the natural cliff ledges that the species prefers for nesting locations. During daytime the falcons have been observed swooping down to catch common city birds such as pigeons and Common Starlings. In many cities, the Falcons have been credited with controlling the numbers of such birds, which have often become pests, without resort to more controversial methods such as poisoning or hunting.

In Virginia, state officials working with students from the Center for Conservation Biology of the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg successfully established nesting boxes high atop the George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge on the York River, the Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge and Varina-Enon Bridge on the James River, and at other similar locations. Thirteen new chicks were hatched in this Virginia program during a recent year. Over 250 falcons have been released through the Virginia program.

In the 53-mile long New River Gorge of West Virginia, another program is underway to re-establish populations by transferring "bridge chicks" from Virginia, Maryland, and New Jersey to special nesting boxes mounted on the high cliffs. [2]. Chicago also started its habitat protection programs with a special recognition of Peregrine Falcon by making it the official bird of the city.[3]

The Peregrine Falcon was removed from the U.S. Threatened and Endangered Species list on August 25, 1999. In 2003, some states began issuing limited numbers of falconry permits for Peregrines, due to the success of the recovery program.

In the UK, there has been a good recovery of populations since the crash of the 1960s. This has been greatly assisted by conservation and protection work led by the RSPB. Peregrines now breed in many mountainous and coastal areas, especially in the west and north. They are also using some city buildings for nesting, capitalizing on the urban pigeon populations for food.

Peregrine Falcon

Falcons see prey at speed of Formula 1 car

by Lund University

Experiment set-up measuring how many blinks per minute a falcon perceives. Credit: Simon Potier

Extremely acute vision and the ability to rapidly process different visual impressions—these two factors are crucial when a peregrine falcon bears down on its prey at a speed that easily matches that of a Formula 1 racing car: over 350 kilometers per hour.

The visual acuity of birds of prey has been studied extensively and shows the vision of some large eagles and vultures is twice as acute as that of humans. On the other hand, up to now researchers have never studied the speed of vision among birds of prey, i.e. how fast they sense visual impressions.

"This is the first time. My colleague Simon Potier and I have examined the peregrine falcon, saker falcon and Harris's hawk and measured how fast light can blink for these species to still register the blinks," says Almut Kelber, professor at the Department of Biology, Lund University.

The results show that the peregrine falcon has the fastest vision and can register 129 Hz (blinks per second) provided the light intensity is high. Under the same conditions, the saker falcon can see 102 Hz and the Harris's hawk 77 Hz. By comparison, humans see a maximum of 50–60 Hz. At the cinema, a speed of 25 images per second is sufficient for us to perceive it as film, and not as a series of still images.

The speed at which the different birds of prey process visual impressions corresponds with the needs they have when hunting: the peregrine falcon hunts fast-flying birds, whereas the Harris's hawk hunts small, slower mammals on the ground.

Even though the vision speed of birds of prey has never been measured before, there are studies about the speed at which small insect-eating birds such as flycatchers and blue tits can take in visual impressions.

"They also have fast vision. Therefore, we draw the conclusion that bird species that hunt prey that flies fast have the fastest vision. Evolution has provided them with the ability because they need it," says Almut Kelber.

"It is something of a competition. A fly flies quite fast and has fast vision, therefore the flycatcher must see the fly quickly in order to catch it. The same applies to the falcon. To capture a flycatcher, the falcon must detect its prey sufficiently early in order to have time to react," says Simon Potier.

The new knowledge can hopefully contribute to better conditions for birds held in captivity.

"Those who keep birds in cages must take care with the lighting and use cage lighting that does not shimmer, flicker or blink, because the birds will not feel well," concludes Almut Kelber.

phys.org/news/2019-12-falcons-prey-formula-car.html

Journal Reference:

Simon Potier et al. How fast can raptors see?, The Journal of Experimental Biology (2019). DOI: 10.1242/jeb.209031

Abstract

Birds, and especially raptors, are highly visual animals. Some of them have the highest spatial resolving power known in the animal kingdom, allowing prey detection at distance. While many raptors visually track fast-moving and manoeuvrable prey, requiring high temporal resolution, this aspect of their visual system has never been studied before. In this study, we estimated how fast raptors can see, by measuring the flicker fusion frequency of three species with different lifestyles. We found that flicker fusion frequency differed among species, being at least 129 Hz in the peregrine falcon Falco peregrinus, 102 Hz in the saker falcon Falco cherrug and 81 Hz in the Harris's hawk Parabuteo unicinctus. We suggest a potential link between fast vision and hunting strategy, with high temporal resolution in the fast-flying falcons that chase fast-moving, manoeuvrable prey and a lower resolution in the Harris's hawk, which flies more slowly and targets slower prey.

jeb.biologists.org/content/early/2019/12/06/jeb.209031

The Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), sometimes formerly known in North America as Duck Hawk, is a medium-sized falcon about the size of a large crow: 380-530 millimetres (15-21 in) long. The English and scientific species names mean "wandering falcon", and refer to the fact that some populations are migratory. It has a wingspan of about 1 meter (40 in). Males weigh 570-710 grams; the noticeably larger females weigh 910-1190 grams.

The Peregrine Falcon is the fastest creature on the planet in its hunting dive, the stoop, in which it soars to a great height, then dives steeply at speeds in excess of 300 km/h (185mph) into either wing of its prey, so as not to harm itself on impact. Although not self-propelled speeds, due to the fact that the falcon gathers the momentum and controls its dive, capture (if any) and landing in its own right, technically there is no faster animal. The fastest speed recorded is 390 km/h (242.3mph).

The fledglings practice the roll and the pumping of the wings before they master the actual stoop.

Range, habitat and subspecies

Peregrine Falcons live mostly along mountain ranges, river valleys, and coastlines and increasingly, in cities. They are widespread throughout the entire world and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

There are many subspecies of Peregrine Falcon, including:

- Falco peregrinus ¡ª the nominate mainly non-migratory race, which breeds over much of western Eurasia

- F.p. anatum ¡ª is mostly found in the Rocky Mountains. Although it used to be common throughout eastern North America, and is currently being re-introduced in the region, it remains uncommon in much of its former range. Most mature anatums, except those that breed in more northern areas, winter in their breeding range. It is a rare vagrant to western Europe.

- F. p. brookei ¡ª of southern Europe to the Caucasus is smaller and more rufous below that the nominate race.

- F. p. calidus ¡ª breeds in the Arctic tundra of Eurasia and is completely migratory and travels as far as sub-Saharan Africa. It is larger and paler than the nominate race.

- F. p. ernesti ¡ª is found in New Zealand and is non-migratory

- F. p, macropus ¡ª is found in Australia and is non-migratory

- F. p. madens ¡ª breeds in the Cape Verde Islands and has brown-washed upperparts.

- F.p. pealei ¡ª or Peale's Falcon, is found in the Pacific Northwest of North America, and is non-migratory. Starting from the Puget Sound it dwells along the coast on cliffs and seastacks up the British Columbia coast (including the Queen Charlotte Islands) around the Gulf of Alaska all the way out the Aleutian Islands towards Russia. This subspecies is the largest in the world and preys mostly on Alcids and seaducks.

- F. p. peregrinator ¡ª (also called the Shaheen Falcon) has rufous underparts and is a breeding resident in South Asia.

- F. p. tundrius ¡ª breeds in the Arctic tundra of North America but is migratory and travels as far as South America.

- The Barbary Falcon, Falco (peregrinus) pelegrinoides, is often considered to be a subspecies of the Peregrine.

Peregrines in mild-winter regions are usually permanent residents, and some birds, especially adult males, will remain on the breeding territory. However, the Arctic subspecies migrate; tundrius birds from Alaska, northern Canada and Greenland migrate to Central and South America, and all calidus birds from northern Eurasia move further south or to coasts in winter.

Australian Peregrine Falcons are non-migratory, and their breeding season is from July to November each year.

Behaviour

Peregrine Falcons feed almost exclusively on birds, such as doves, waterfowl and songbirds, but occasionally they hunt small mammals, including bats, rats, voles and rabbits. Insects and reptiles make up a relatively small proportion of their diet. On the other hand, a growing number of city-dwelling Falcons find that feral pigeons and Common Starlings provide plenty of food. Peregrine Falcon also eat thier own chicks when starving.

Peregrine Falcons breed at approximately two or three years of age. They mate for life and return to the same nesting spot annually. Their courtship flight includes a mix of aerial acrobatics, precise spirals, and steep dives. The male passes prey it has caught to the female in midair. To make this possible, the female actually flies upside-down to receive the food from the male's talons. Females lay an average clutch of three or four eggs in a scrape, normally on cliff edges or, increasingly, on tall buildings or bridges. They occasionally nest in tree hollows or in the disused nest of other large birds.

The laying date varies according to locality, but is generally:

from February to March (in the Northern Hemisphere)

from July to August (in the Southern Hemisphere)

The females incubate the eggs for twenty-nine to thirty-two days at which point the eggs hatch. While the males also sometimes help with the incubation of the eggs, they only do so occasionally and for short periods.

Thirty-five to forty-two days after hatching, the chicks will fledge, but they tend to remain dependent on their parents for a further two months. The tiercel, or male, provides most of the food for himself, the female, and the chicks; the falcon, or female, stays and watches the young.

The average life span of a Peregrine Falcon is approximately eight to ten years, although some have been recorded to live until slightly more than twenty years of age.

Threats

The Peregrine Falcon became endangered because of the overuse of pesticides, during the 1950s and 1960s. Pesticide build-up interfered with reproduction, thinning eggshells and severely restricting the ability of birds to reproduce. The DDT buildup in the falcon's fat tissues would result in less calcium in the eggshells, leading to flimsier, more fragile eggs. In several parts of the world, this species was wiped out by pesticides.

Peregrine eggs and chicks are often targeted by thieves and collectors, so it is normal practice not to publicise unprotected nest locations.

Recovery efforts

Wildlife services around the world organized Peregrine Falcon recovery teams to breed them in captivity.

The birds were fed through a chute, so they could not see the human trainers. Then, when they were old enough, the box was opened. This allowed the bird to test its wings. As the bird got stronger, the food was reduced because the bird could hunt its own food. This procedure is called hacking. To release a captive-bred falcon, the bird was placed in a special box at the top of a tower or cliff ledge.

Worldwide recovery efforts have been remarkably successful. In the United States, the banning of DDT eventually allowed released birds to breed successfully. There are now dozens of breeding pairs of Peregrine Falcons in the northeastern USA and Canada.

Many have settled in large cities, including London Ontario and Derby, where they nest on cathedrals, skyscraper window ledges, and the towers of suspension bridges. About 18 pairs nested in New York City in 2005.

These structures typically closely resemble the natural cliff ledges that the species prefers for nesting locations. During daytime the falcons have been observed swooping down to catch common city birds such as pigeons and Common Starlings. In many cities, the Falcons have been credited with controlling the numbers of such birds, which have often become pests, without resort to more controversial methods such as poisoning or hunting.

In Virginia, state officials working with students from the Center for Conservation Biology of the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg successfully established nesting boxes high atop the George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge on the York River, the Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge and Varina-Enon Bridge on the James River, and at other similar locations. Thirteen new chicks were hatched in this Virginia program during a recent year. Over 250 falcons have been released through the Virginia program.

In the 53-mile long New River Gorge of West Virginia, another program is underway to re-establish populations by transferring "bridge chicks" from Virginia, Maryland, and New Jersey to special nesting boxes mounted on the high cliffs. [2]. Chicago also started its habitat protection programs with a special recognition of Peregrine Falcon by making it the official bird of the city.[3]

The Peregrine Falcon was removed from the U.S. Threatened and Endangered Species list on August 25, 1999. In 2003, some states began issuing limited numbers of falconry permits for Peregrines, due to the success of the recovery program.

In the UK, there has been a good recovery of populations since the crash of the 1960s. This has been greatly assisted by conservation and protection work led by the RSPB. Peregrines now breed in many mountainous and coastal areas, especially in the west and north. They are also using some city buildings for nesting, capitalizing on the urban pigeon populations for food.

Peregrine Falcon

Falcons see prey at speed of Formula 1 car

by Lund University

Experiment set-up measuring how many blinks per minute a falcon perceives. Credit: Simon Potier

Extremely acute vision and the ability to rapidly process different visual impressions—these two factors are crucial when a peregrine falcon bears down on its prey at a speed that easily matches that of a Formula 1 racing car: over 350 kilometers per hour.

The visual acuity of birds of prey has been studied extensively and shows the vision of some large eagles and vultures is twice as acute as that of humans. On the other hand, up to now researchers have never studied the speed of vision among birds of prey, i.e. how fast they sense visual impressions.

"This is the first time. My colleague Simon Potier and I have examined the peregrine falcon, saker falcon and Harris's hawk and measured how fast light can blink for these species to still register the blinks," says Almut Kelber, professor at the Department of Biology, Lund University.

The results show that the peregrine falcon has the fastest vision and can register 129 Hz (blinks per second) provided the light intensity is high. Under the same conditions, the saker falcon can see 102 Hz and the Harris's hawk 77 Hz. By comparison, humans see a maximum of 50–60 Hz. At the cinema, a speed of 25 images per second is sufficient for us to perceive it as film, and not as a series of still images.

The speed at which the different birds of prey process visual impressions corresponds with the needs they have when hunting: the peregrine falcon hunts fast-flying birds, whereas the Harris's hawk hunts small, slower mammals on the ground.

Even though the vision speed of birds of prey has never been measured before, there are studies about the speed at which small insect-eating birds such as flycatchers and blue tits can take in visual impressions.

"They also have fast vision. Therefore, we draw the conclusion that bird species that hunt prey that flies fast have the fastest vision. Evolution has provided them with the ability because they need it," says Almut Kelber.

"It is something of a competition. A fly flies quite fast and has fast vision, therefore the flycatcher must see the fly quickly in order to catch it. The same applies to the falcon. To capture a flycatcher, the falcon must detect its prey sufficiently early in order to have time to react," says Simon Potier.

The new knowledge can hopefully contribute to better conditions for birds held in captivity.

"Those who keep birds in cages must take care with the lighting and use cage lighting that does not shimmer, flicker or blink, because the birds will not feel well," concludes Almut Kelber.

phys.org/news/2019-12-falcons-prey-formula-car.html

Journal Reference:

Simon Potier et al. How fast can raptors see?, The Journal of Experimental Biology (2019). DOI: 10.1242/jeb.209031

Abstract

Birds, and especially raptors, are highly visual animals. Some of them have the highest spatial resolving power known in the animal kingdom, allowing prey detection at distance. While many raptors visually track fast-moving and manoeuvrable prey, requiring high temporal resolution, this aspect of their visual system has never been studied before. In this study, we estimated how fast raptors can see, by measuring the flicker fusion frequency of three species with different lifestyles. We found that flicker fusion frequency differed among species, being at least 129 Hz in the peregrine falcon Falco peregrinus, 102 Hz in the saker falcon Falco cherrug and 81 Hz in the Harris's hawk Parabuteo unicinctus. We suggest a potential link between fast vision and hunting strategy, with high temporal resolution in the fast-flying falcons that chase fast-moving, manoeuvrable prey and a lower resolution in the Harris's hawk, which flies more slowly and targets slower prey.

jeb.biologists.org/content/early/2019/12/06/jeb.209031