Post by Eaglehawk on Dec 6, 2019 4:25:42 GMT

Eurasian Skylark - Alauda arvensis

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Alaudidae

Genus: Alauda

Species: Alauda arvensis Linnaeus, 1758

The Eurasian skylark (Alauda arvensis) is a passerine bird in the lark family Alaudidae. It is a widespread species found across Europe and Asia with introduced populations in New Zealand, Australia and on the Hawaiian Islands. It is a bird of open farmland and heath, known for the song of the male, which is delivered in hovering flight from heights of 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft). The sexes are alike. It is streaked greyish-brown above and on the breast and has a buff-white belly.

The female Eurasian skylark builds an open nest in a shallow depression on open ground well away from trees, bushes and hedges. She lays three to five eggs which she incubates for around 11 days. The chicks are fed by both parents but leave the nest after eight to ten days, well before they can fly. They scatter and hide in the vegetation but continue to be fed by the parents until they can fly at 18 to 20 days of age. Nests are subject to high predation rates by larger birds and small mammals. The parents can have several broods in a single season.

Taxonomy and systematics

The Eurasian skylark was described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae and retains its original binomial name of Alauda arvensis. It is one of the four species placed in the genus Alauda. The genus name is from the Latin alauda, "lark". Pliny thought the word was originally of Celtic origin. The specific arvensis is also Latin, and means "of the field". The results of a molecular phylogenetic study of the lark family Alaudidae published in 2013 suggested that Eurasian skylark is most closely related to the Oriental skylark Alauda gulgula.

Formerly, many authorities considered the Japanese skylark as a separate species. It is now usually considered a subspecies of the Eurasian skylark. Alternate names for the Eurasian skylark include northern skylark and sky lark.

Subspecies

Eleven subspecies are recognized:

A. a. arvensis Linnaeus, 1758 – northern, western and central Europe

A. a. sierrae Weigold, 1913 – Portugal, central and southern Spain

A. a. harterti Whitaker, 1904 – north-western Africa

A. a. cantarella Bonaparte, 1850 – southern Europe from north-eastern Spain to Turkey and the Caucasus

A. a. armenica Bogdanov, 1879 – south-eastern Turkey to Iran

A. a. dulcivox Hume, 1872 – south-eastern European Russia and western Siberia to north-western China and south-western Mongolia

A. a. kiborti Zaliesski, 1917 – southern Siberia, northern and eastern Mongolia and north-eastern China

A. a. intermedia Swinhoe, 1863 – north-central Siberia to north-eastern China and Korea

A. a. pekinensis Swinhoe, 1863 – north-eastern Siberia, Kamchatka Peninsula and the Kuril Islands

A. a. lonnbergi Hachisuka, 1926 – northern Sakhalin Island

A. a. japonica Temminck & Schlegel, 1848 – southern Sakhalin Island, southern Kuril Island, Japan and the Ryukyu Islands: the Japanese skylark

Some authorities recognise the subspecies A. a. scotia Tschusi, 1903 and A. a. guillelmi Witherby, 1921. In the above list scotia is included in the nominate subspecies A. a. arvensis and guillelmi is included in A. a. sierrae.

Description

The Eurasian skylark is 18–19 cm (7.1–7.5 in) in length. Like most other larks, the Eurasian skylark is a rather dull-looking species, being mainly brown above and paler below. It has a short blunt crest on the head, which can be raised and lowered. In flight it shows a short tail and short broad wings. The tail and the rear edge of the wings are edged with white, which are visible when the bird is flying away, but not if it is heading towards the observer. The male has broader wings than the female. This adaptation for more efficient hovering flight may have evolved because of female Eurasian skylarks' preference for males that sing and hover for longer periods and so demonstrate that they are likely to have good overall fitness.

It is known for the song of the male, which is delivered in hovering flight from heights of 50 to 100 m, when the singing bird may appear as just a dot in the sky from the ground. The long, unbroken song is a clear, bubbling warble delivered high in the air while the bird is rising, circling or hovering. The song generally lasts two to three minutes, but it tends to last longer later in the mating season, when songs can last for 20 minutes or more. At wind farm sites, male skylarks have been found to sing at higher frequencies as a result of wind turbine noise.

Distribution and habitat

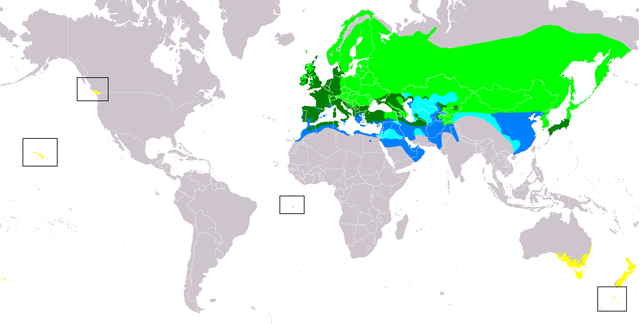

This lark breeds across most of Europe and Asia and in the mountains of north Africa. It is mainly resident in the west of its range, but eastern populations are more migratory, moving further south in winter. Even in the milder west of its range, many birds move to lowlands and the coast in winter. Asian birds, subspecies A. a. pekinensis, appear as vagrants in Alaska.

Range of A. arvensis

Breeding

Resident

Passage

Non-breeding

Extant & Introduced (resident)

Possible extinct & Introduced

Introduced populations

In the 19th century multiple batches of Eurasian skylarks were released in New Zealand beginning in 1864 in Nelson (in the South Island) and in 1867 in Auckland (in the North Island). The wild population increased rapidly and had spread throughout both the North and South Islands by the 1920s.

In Australia the Eurasian skylark was introduced on multiple occasions beginning in 1850. It is now widespread in the southeast of the continent. In New South Wales it mostly occurs south of 33°S. It is widespread throughout Victoria and Tasmania and also occurs in the south-eastern corner of South Australia around Adelaide.

The Eurasian skylark was introduced to the southeastern Hawaiian Islands beginning in 1865. Although once common, it has declined in abundance on Oahu and is no longer found on Kauai. A study published in 1986 found European skylarks remained only on the islands of Hawaii and Maui and estimated a total population of 10,000 individuals.

The Eurasian skylark was introduced to Vancouver Island off the west coast of Canada in 1903; additional birds were introduced in 1913. The population grew and by 1962 there were around 1000 individuals. The numbers have subsequently declined due to loss of habitat, and in 2007 there were estimated to be only around 100 individuals spread over four small areas of the Saanich Peninsula.

Behaviour and ecology

Breeding

Eurasian skylarks first breed when they are one year of age. Nesting may start in late March or early April. The nest is probably built by the female alone and is a shallow depression in the ground lined with grasses. The clutch is 3 to 5 eggs. The eggs of the nominate subspecies average 23.4 mm × 16.8 mm (0.92 in × 0.66 in) in size and weigh around 3.35 g (0.118 oz). They have a grey-white or greenish background and are covered in brown or olive spots. They are incubated only by the female beginning after the last egg is laid and hatch synchronously after 11 days. The altricial young are cared for by both parents and for the first week are fed almost exclusively on insects. The nestlings fledge after 18 to 20 days but they usually leave the nest after 8 to 10 days. They are independent of their parents after around 25 days. The parents can have up to 4 broods in a season.

Feeding

The Eurasian skylark walks over the ground searching for food on the soil surface. Its diet consists of insects and plant material such as seeds and young leaves. Unlike a finch (family Fringillidae) it swallows seeds without removing the husk. Insects form an important part of the diet in summer.

Threats

In the UK, Eurasian skylark numbers have declined over the last 30 years, as determined by the Common Bird Census started in the early 1960s by the British Trust for Ornithology. There are now only 10% of the numbers that were present 30 years ago. The RSPB have shown that this large decline is mainly due to changes in farming practices and only partly due to pesticides. In the past cereals were planted in the spring, grown through the summer and harvested in the early autumn. Cereals are now planted in the autumn, grown through the winter and are harvested in the early summer. The winter grown fields are much too dense in summer for the Eurasian skylark to be able to walk and run between the wheat stems to find its food.

English farmers are now encouraged and paid to maintain and create biodiversity for improving the habitat for Eurasian skylarks. Natural England's Environmental Stewardship Scheme offers 5 and 10-year grants for various beneficial options. For example, there is an option where the farmer can opt to grow a spring cereal instead of a winter one, and leave the stubble untreated with pesticide over the winter. The British Trust for Ornithology likens the stubbles to "giant bird tables" – providing spilt grain and weed seed to foraging birds.

The RSPB's research, over a six-year period, of winter-planted wheat fields has shown that suitable nesting areas for Eurasian skylarks can be made by turning the seeding machine off (or lifting the drill) for a 5 to 10 metres stretch as the tractor goes over the ground to briefly stop the seeds being sown. This is repeated in several areas within the same field to make about two skylark plots per hectare. Subsequent spraying and fertilising can be continuous over the entire field. DEFRA suggests that Eurasian skylark plots should not be nearer than 24 m to the perimeter of the field, should not be near to telegraph poles, and should not be enclosed by trees.

When the crop grows, the Eurasian skylark plots (areas without crop seeds) become areas of low vegetation where Eurasian skylarks can easily hunt insects, and can build their well camouflaged ground nests. These areas of low vegetation are just right for skylarks, but the wheat in the rest of the field becomes too closely packed and too tall for the bird to seek food. At the RSPB's research farm in Cambridgeshire skylark numbers have increased threefold (from 10 pairs to 30 pairs) over six years. Fields where Eurasian skylarks were seen the year before (or nearby) would be obvious good sites for skylark plots. Farmers have reported that skylark plots are easy to make and the RSPB hope that this simple effective technique can be copied nationwide.

Record-size sex chromosome found in two bird species

Date: December 4, 2019

Source: Lund University

Researchers in Sweden and the UK have discovered the largest known avian sex chromosome. The giant chromosome was created when four chromosomes fused together into one, and has been found in two species of lark.

"This was an unexpected discovery, as birds are generally considered to have very stable genetic material with well-preserved chromosomes," explains Bengt Hansson, professor at Lund University in Sweden.

In a new study, the researchers charted the genome of several species of lark, a songbird family in which all members have unusually large sex chromosomes. The record-size chromosome is found in both the Eurasian skylark, a species that is common in Europe, Asia and North Africa, and the Raso lark, a species only found on the small island of Raso in Cape Verde.

According to the Lund biologists Bengt Hansson and Hanna Sigeman, who led the study, the four chromosomes have fused together in stages. The oldest fusion happened 25 million years ago and the most recent six million years ago. The four chromosomes that have formed the larks' sex chromosome have also all developed at some time into sex chromosomes in other vertebrates.

"The genetic material in the larks' sex chromosome has also been used to form sex chromosomes in mammals, fish, frogs, lizards and turtles. This indicates that certain parts of the genome have a greater tendency to develop into sex chromosomes than others," says Bengt Hansson.

Why the two species have the largest sex chromosome of all birds is unclear, but the result could be disastrous lead to problems for female larks in the future. Studies of different sex chromosome systems have shown that the sex-limited chromosome, for example the Y chromosome in humans, usually breaks down over time and loses functional genes.

"Among birds, the females have a corresponding W chromosome in which we see the same breakdown pattern. As three times more genetic material is linked to the sex chromosomes of these larks compared to other birds, this could cause problems for many genes," says Hanna Sigeman, doctoral student at the Department of Biology, Lund University.

Story Source: Lund University. "Record-size sex chromosome found in two bird species." ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/12/191204124552.htm (accessed December 5, 2019).

Journal Reference:

Hanna Sigeman, Suvi Ponnikas, Pallavi Chauhan, Elisa Dierickx, M. de L. Brooke, Bengt Hansson. Repeated sex chromosome evolution in vertebrates supported by expanded avian sex chromosomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2019; 286 (1916): 20192051 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2019.2051

Abstract

Sex chromosomes have evolved from the same autosomes multiple times across vertebrates, suggesting that selection for recombination suppression has acted repeatedly and independently on certain genetic backgrounds. Here, we perform comparative genomics of a bird clade (larks and their sister lineage; Alaudidae and Panuridae) where multiple autosome–sex chromosome fusions appear to have formed expanded sex chromosomes. We detected the largest known avian sex chromosome (195.3 Mbp) and show that it originates from fusions between parts of four avian chromosomes: Z, 3, 4A and 5. Within these four chromosomes, we found evidence of five evolutionary strata where recombination had been suppressed at different time points, and show that stratum age explained the divergence rate of Z–W gametologs. Next, we analysed chromosome content and found that chromosome 3 was significantly enriched for genes with predicted sex-related functions. Finally, we demonstrate extensive homology to sex chromosomes in other vertebrate lineages: chromosomes Z, 3, 4A and 5 have independently evolved into sex chromosomes in fish (Z), turtles (Z, 5), lizards (Z, 4A), mammals (Z, 4A) and frogs (Z, 3, 4A, 5). Our results provide insights into and support for repeated evolution of sex chromosomes in vertebrates.

royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2019.2051

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Alaudidae

Genus: Alauda

Species: Alauda arvensis Linnaeus, 1758

The Eurasian skylark (Alauda arvensis) is a passerine bird in the lark family Alaudidae. It is a widespread species found across Europe and Asia with introduced populations in New Zealand, Australia and on the Hawaiian Islands. It is a bird of open farmland and heath, known for the song of the male, which is delivered in hovering flight from heights of 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft). The sexes are alike. It is streaked greyish-brown above and on the breast and has a buff-white belly.

The female Eurasian skylark builds an open nest in a shallow depression on open ground well away from trees, bushes and hedges. She lays three to five eggs which she incubates for around 11 days. The chicks are fed by both parents but leave the nest after eight to ten days, well before they can fly. They scatter and hide in the vegetation but continue to be fed by the parents until they can fly at 18 to 20 days of age. Nests are subject to high predation rates by larger birds and small mammals. The parents can have several broods in a single season.

Taxonomy and systematics

The Eurasian skylark was described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae and retains its original binomial name of Alauda arvensis. It is one of the four species placed in the genus Alauda. The genus name is from the Latin alauda, "lark". Pliny thought the word was originally of Celtic origin. The specific arvensis is also Latin, and means "of the field". The results of a molecular phylogenetic study of the lark family Alaudidae published in 2013 suggested that Eurasian skylark is most closely related to the Oriental skylark Alauda gulgula.

Formerly, many authorities considered the Japanese skylark as a separate species. It is now usually considered a subspecies of the Eurasian skylark. Alternate names for the Eurasian skylark include northern skylark and sky lark.

Subspecies

Eleven subspecies are recognized:

A. a. arvensis Linnaeus, 1758 – northern, western and central Europe

A. a. sierrae Weigold, 1913 – Portugal, central and southern Spain

A. a. harterti Whitaker, 1904 – north-western Africa

A. a. cantarella Bonaparte, 1850 – southern Europe from north-eastern Spain to Turkey and the Caucasus

A. a. armenica Bogdanov, 1879 – south-eastern Turkey to Iran

A. a. dulcivox Hume, 1872 – south-eastern European Russia and western Siberia to north-western China and south-western Mongolia

A. a. kiborti Zaliesski, 1917 – southern Siberia, northern and eastern Mongolia and north-eastern China

A. a. intermedia Swinhoe, 1863 – north-central Siberia to north-eastern China and Korea

A. a. pekinensis Swinhoe, 1863 – north-eastern Siberia, Kamchatka Peninsula and the Kuril Islands

A. a. lonnbergi Hachisuka, 1926 – northern Sakhalin Island

A. a. japonica Temminck & Schlegel, 1848 – southern Sakhalin Island, southern Kuril Island, Japan and the Ryukyu Islands: the Japanese skylark

Some authorities recognise the subspecies A. a. scotia Tschusi, 1903 and A. a. guillelmi Witherby, 1921. In the above list scotia is included in the nominate subspecies A. a. arvensis and guillelmi is included in A. a. sierrae.

Description

The Eurasian skylark is 18–19 cm (7.1–7.5 in) in length. Like most other larks, the Eurasian skylark is a rather dull-looking species, being mainly brown above and paler below. It has a short blunt crest on the head, which can be raised and lowered. In flight it shows a short tail and short broad wings. The tail and the rear edge of the wings are edged with white, which are visible when the bird is flying away, but not if it is heading towards the observer. The male has broader wings than the female. This adaptation for more efficient hovering flight may have evolved because of female Eurasian skylarks' preference for males that sing and hover for longer periods and so demonstrate that they are likely to have good overall fitness.

It is known for the song of the male, which is delivered in hovering flight from heights of 50 to 100 m, when the singing bird may appear as just a dot in the sky from the ground. The long, unbroken song is a clear, bubbling warble delivered high in the air while the bird is rising, circling or hovering. The song generally lasts two to three minutes, but it tends to last longer later in the mating season, when songs can last for 20 minutes or more. At wind farm sites, male skylarks have been found to sing at higher frequencies as a result of wind turbine noise.

Distribution and habitat

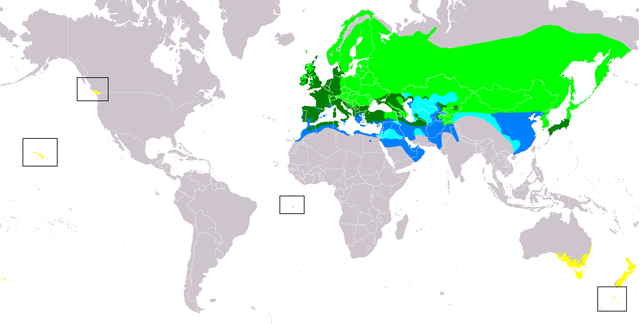

This lark breeds across most of Europe and Asia and in the mountains of north Africa. It is mainly resident in the west of its range, but eastern populations are more migratory, moving further south in winter. Even in the milder west of its range, many birds move to lowlands and the coast in winter. Asian birds, subspecies A. a. pekinensis, appear as vagrants in Alaska.

Range of A. arvensis

Breeding

Resident

Passage

Non-breeding

Extant & Introduced (resident)

Possible extinct & Introduced

Introduced populations

In the 19th century multiple batches of Eurasian skylarks were released in New Zealand beginning in 1864 in Nelson (in the South Island) and in 1867 in Auckland (in the North Island). The wild population increased rapidly and had spread throughout both the North and South Islands by the 1920s.

In Australia the Eurasian skylark was introduced on multiple occasions beginning in 1850. It is now widespread in the southeast of the continent. In New South Wales it mostly occurs south of 33°S. It is widespread throughout Victoria and Tasmania and also occurs in the south-eastern corner of South Australia around Adelaide.

The Eurasian skylark was introduced to the southeastern Hawaiian Islands beginning in 1865. Although once common, it has declined in abundance on Oahu and is no longer found on Kauai. A study published in 1986 found European skylarks remained only on the islands of Hawaii and Maui and estimated a total population of 10,000 individuals.

The Eurasian skylark was introduced to Vancouver Island off the west coast of Canada in 1903; additional birds were introduced in 1913. The population grew and by 1962 there were around 1000 individuals. The numbers have subsequently declined due to loss of habitat, and in 2007 there were estimated to be only around 100 individuals spread over four small areas of the Saanich Peninsula.

Behaviour and ecology

Breeding

Eurasian skylarks first breed when they are one year of age. Nesting may start in late March or early April. The nest is probably built by the female alone and is a shallow depression in the ground lined with grasses. The clutch is 3 to 5 eggs. The eggs of the nominate subspecies average 23.4 mm × 16.8 mm (0.92 in × 0.66 in) in size and weigh around 3.35 g (0.118 oz). They have a grey-white or greenish background and are covered in brown or olive spots. They are incubated only by the female beginning after the last egg is laid and hatch synchronously after 11 days. The altricial young are cared for by both parents and for the first week are fed almost exclusively on insects. The nestlings fledge after 18 to 20 days but they usually leave the nest after 8 to 10 days. They are independent of their parents after around 25 days. The parents can have up to 4 broods in a season.

Feeding

The Eurasian skylark walks over the ground searching for food on the soil surface. Its diet consists of insects and plant material such as seeds and young leaves. Unlike a finch (family Fringillidae) it swallows seeds without removing the husk. Insects form an important part of the diet in summer.

Threats

In the UK, Eurasian skylark numbers have declined over the last 30 years, as determined by the Common Bird Census started in the early 1960s by the British Trust for Ornithology. There are now only 10% of the numbers that were present 30 years ago. The RSPB have shown that this large decline is mainly due to changes in farming practices and only partly due to pesticides. In the past cereals were planted in the spring, grown through the summer and harvested in the early autumn. Cereals are now planted in the autumn, grown through the winter and are harvested in the early summer. The winter grown fields are much too dense in summer for the Eurasian skylark to be able to walk and run between the wheat stems to find its food.

English farmers are now encouraged and paid to maintain and create biodiversity for improving the habitat for Eurasian skylarks. Natural England's Environmental Stewardship Scheme offers 5 and 10-year grants for various beneficial options. For example, there is an option where the farmer can opt to grow a spring cereal instead of a winter one, and leave the stubble untreated with pesticide over the winter. The British Trust for Ornithology likens the stubbles to "giant bird tables" – providing spilt grain and weed seed to foraging birds.

The RSPB's research, over a six-year period, of winter-planted wheat fields has shown that suitable nesting areas for Eurasian skylarks can be made by turning the seeding machine off (or lifting the drill) for a 5 to 10 metres stretch as the tractor goes over the ground to briefly stop the seeds being sown. This is repeated in several areas within the same field to make about two skylark plots per hectare. Subsequent spraying and fertilising can be continuous over the entire field. DEFRA suggests that Eurasian skylark plots should not be nearer than 24 m to the perimeter of the field, should not be near to telegraph poles, and should not be enclosed by trees.

When the crop grows, the Eurasian skylark plots (areas without crop seeds) become areas of low vegetation where Eurasian skylarks can easily hunt insects, and can build their well camouflaged ground nests. These areas of low vegetation are just right for skylarks, but the wheat in the rest of the field becomes too closely packed and too tall for the bird to seek food. At the RSPB's research farm in Cambridgeshire skylark numbers have increased threefold (from 10 pairs to 30 pairs) over six years. Fields where Eurasian skylarks were seen the year before (or nearby) would be obvious good sites for skylark plots. Farmers have reported that skylark plots are easy to make and the RSPB hope that this simple effective technique can be copied nationwide.

Record-size sex chromosome found in two bird species

Date: December 4, 2019

Source: Lund University

Researchers in Sweden and the UK have discovered the largest known avian sex chromosome. The giant chromosome was created when four chromosomes fused together into one, and has been found in two species of lark.

"This was an unexpected discovery, as birds are generally considered to have very stable genetic material with well-preserved chromosomes," explains Bengt Hansson, professor at Lund University in Sweden.

In a new study, the researchers charted the genome of several species of lark, a songbird family in which all members have unusually large sex chromosomes. The record-size chromosome is found in both the Eurasian skylark, a species that is common in Europe, Asia and North Africa, and the Raso lark, a species only found on the small island of Raso in Cape Verde.

According to the Lund biologists Bengt Hansson and Hanna Sigeman, who led the study, the four chromosomes have fused together in stages. The oldest fusion happened 25 million years ago and the most recent six million years ago. The four chromosomes that have formed the larks' sex chromosome have also all developed at some time into sex chromosomes in other vertebrates.

"The genetic material in the larks' sex chromosome has also been used to form sex chromosomes in mammals, fish, frogs, lizards and turtles. This indicates that certain parts of the genome have a greater tendency to develop into sex chromosomes than others," says Bengt Hansson.

Why the two species have the largest sex chromosome of all birds is unclear, but the result could be disastrous lead to problems for female larks in the future. Studies of different sex chromosome systems have shown that the sex-limited chromosome, for example the Y chromosome in humans, usually breaks down over time and loses functional genes.

"Among birds, the females have a corresponding W chromosome in which we see the same breakdown pattern. As three times more genetic material is linked to the sex chromosomes of these larks compared to other birds, this could cause problems for many genes," says Hanna Sigeman, doctoral student at the Department of Biology, Lund University.

Story Source: Lund University. "Record-size sex chromosome found in two bird species." ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/12/191204124552.htm (accessed December 5, 2019).

Journal Reference:

Hanna Sigeman, Suvi Ponnikas, Pallavi Chauhan, Elisa Dierickx, M. de L. Brooke, Bengt Hansson. Repeated sex chromosome evolution in vertebrates supported by expanded avian sex chromosomes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2019; 286 (1916): 20192051 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2019.2051

Abstract

Sex chromosomes have evolved from the same autosomes multiple times across vertebrates, suggesting that selection for recombination suppression has acted repeatedly and independently on certain genetic backgrounds. Here, we perform comparative genomics of a bird clade (larks and their sister lineage; Alaudidae and Panuridae) where multiple autosome–sex chromosome fusions appear to have formed expanded sex chromosomes. We detected the largest known avian sex chromosome (195.3 Mbp) and show that it originates from fusions between parts of four avian chromosomes: Z, 3, 4A and 5. Within these four chromosomes, we found evidence of five evolutionary strata where recombination had been suppressed at different time points, and show that stratum age explained the divergence rate of Z–W gametologs. Next, we analysed chromosome content and found that chromosome 3 was significantly enriched for genes with predicted sex-related functions. Finally, we demonstrate extensive homology to sex chromosomes in other vertebrate lineages: chromosomes Z, 3, 4A and 5 have independently evolved into sex chromosomes in fish (Z), turtles (Z, 5), lizards (Z, 4A), mammals (Z, 4A) and frogs (Z, 3, 4A, 5). Our results provide insights into and support for repeated evolution of sex chromosomes in vertebrates.

royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2019.2051