Post by Eaglehawk on Nov 27, 2019 6:40:46 GMT

Great Auk - Pinguinus impennis

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

Genus: Pinguinus

Species: P. impennis

Conservation Status: Extinct

The Great Auk, Pinguinus impennis, formerly of the genus Alca, was a large, flightless alcid that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It was the only modern species in the genus Pinguinus, a group of birds that formerly included one other species of flightless giant auk from the Atlantic Ocean region. It bred on rocky, isolated islands with easy access to both the ocean and a plentiful food supply, a rarity in nature that provided only a few breeding sites for the auks. When not breeding, the auks spent their time foraging in the waters of the North Atlantic, ranging as far south as New England and northern Spain through Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Ireland, and Great Britain.

The Great Auk was 75 to 85 centimetres (30 to 33 in) tall and weighed around 5 kilograms (11 lb), making it the largest member of the alcid family. It had a black back and a white belly. The black beak was heavy and hooked with grooves etched into its surface. During the breeding season, the Great Auk had a white patch over each eye. After the breeding season, the auk lost this patch, instead developing a white band stretching between the eyes. The wings were 15 centimetres (5.9 in) long, rendering the bird flightless. Instead, the auk was a powerful swimmer, a trait that it used in hunting. Its favorite prey were fish, including Atlantic Menhaden and Capelin, and crustaceans. Although agile in the water, it was clumsy on land. Its main predators were Orcas, White-tailed Eagles, Polar Bears, and humans. Great Auk pairs mated for life. They nested in extremely dense and social colonies, laying one egg on bare rock. The egg was white with variable brown streaking. Both parents incubated for about six weeks before their young hatched. The young auks left the nest site after two or three weeks and the parents continued to care for them.

Humans had hunted the Great Auk for more than 100,000 years. It was an important part of many Native American cultures which coexisted with the bird, both as a food source and as a symbolic item. Many Maritime Archaic people were buried with Great Auk bones, and one was buried with a cloak made of over 200 auk skins. Early European explorers to the Americas used the auk as a convenient food source or as fishing bait, reducing its numbers. The bird's down was in high demand in Europe, a factor which largely eliminated the European populations by the mid-16th century. Scientists soon began to realize that the Great Auk was disappearing and it became the beneficiary of many early environmental laws, but this proved not to be enough. Its growing rarity increased interest from European museums and private collectors in obtaining skins and eggs of the bird. This trend eliminated the last of the Great Auks on 3 July 1844 on Eldey, Iceland. However, a record of a bird in 1852 is considered by some to be the last sighting of this species. The Great Auk is mentioned in a number of novels and the scientific journal of the American Ornithologists' Union is named The Auk in honor of this bird.

Taxonomy

The Great Auk was one of the 4400 animal species originally described by Carolus Linnaeus in his 18th century work, Systema Naturae, in which it was named Alca impennis. The species was not placed in its own genus, Pinguinus, until 1791. The generic name is derived from the Spanish and Portuguese name for the species, while the specific name impennis is from Latin and refers to the lack of flight feathers or pennae.

Analysis of mtDNA sequences have confirmed morphological and biogeographical studies in regarding the Razorbill as the Great Auk's closest living relative. The Great Auk was also closely related to the Little Auk (Dovekie), which underwent a radically different evolution compared to Pinguinus. Due to its outward similarity to the Razorbill (apart from flightlessness and size), the Great Auk was often placed in the genus Alca, following Linnaeus. The name Alca is a Latin derivative of the Scandinavian word for Razorbills and their relatives.

The fossil record (especially Pinguinus alfrednewtoni) and molecular evidence demonstrate that the three genera, while closely related, diverged soon after their common ancestor, a bird probably similar to a stout Xantus's Murrelet, had spread to the coasts of the Atlantic. By that time the murres, or Atlantic guillemots, had apparently already split off from the other Atlantic alcids. Razorbill-like birds were common in the Atlantic during the Pliocene, but the evolution of the Little Auk is sparsely documented. The molecular data are compatible with either view, but the weight of evidence suggests placing the Great Auk in a distinct genus. The Great Auk was not closely related to the other extinct genera of flightless alcids, Mancalla, Praemancalla, and Alcodes.

Pinguinus alfrednewtoni was a larger though also flightless member of the genus Pinguinus that lived during the Early Pliocene. Known from bones found in the Yorktown Formation of the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina, it is believed to have split along with the Great Auk from a common ancestor. Pinguinus alfrednewtoni lived in the western Atlantic while the Great Auk lived in the eastern Atlantic, but after the former died out after the Pliocene, the Great Auk replaced it.

The Basque name for the Great Auk is arponaz while the early French name was apponatz, both meaning "spearbill". The Norse called the Great Auk geirfugl, which means "spearbird". This has led to an alternative common name for the bird, "garefowl". Spanish and Portuguese sailors called the bird pingüinos. The Inuit name for the Great Auk was isarukitsck, which meant "little wing". The Welsh people referred to this species as "pingwen" (actually spelled "pengwyn" - lit. white head). When European explorers discovered what are today known as penguins in the Southern Hemisphere, they noticed their similar appearance to the Great Auk and named them after this bird, despite the fact that they are not related.

Description

Standing about 75 to 85 centimetres (30 to 33 in) tall and weighing around 5 kilograms (11 lb), the flightless Great Auk was the largest of both its family and the order Charadriiformes. The auks which lived further north averaged larger in size than the more southerly members of the species. Males and females were similar in plumage, although there is evidence for differences in size, particularly in the bill and femur length. The back was primarily a glossy black, while the stomach was white. The neck and legs were short, and the head and wings small. The auk appeared chubby due to a thick layer of fat necessary for warmth. During the breeding season, the Great Auk developed a wide white eye patch over the eye, which had a hazel or chestnut iris. After the breeding season the auk molted and lost this eye patch, which was replaced with a wide white band and a gray line of feathers which stretched from the eye to the ear. During the summer, the auk's chin and throat were blackish-brown, while the inside of the mouth was yellow. During the winter, this alcid molted and the throat became white. The bill was large at 11 centimetres (4.3 in) long and curved downwards at the top; the bill also had deep white grooves in both the upper and lower mandibles, up to seven on the upper mandible and twelve on the lower mandible in summer, though there were fewer in winter. The wings were only 15 centimetres (5.9 in) in length and the longest wing feathers were only 10 centimetres (3.9 in) long. Its feet and short claws were black while the webbed skin between the toes was brownish black. The legs were far back on the bird's body, which gave it powerful swimming and diving abilities.

Hatchlings were gray and downy. Juvenile birds had less prominent grooves in their beaks and had mottled white and black necks, while the eye spot found in adults was not present; instead, a gray line ran through the eyes (which still had the white eye ring) to just below the ears.

The auk's calls included low croaking and a hoarse scream. A captive auk was observed making a gurgling noise when anxious. It is not known what its other vocalizations were like, but it is believed that they were similar to those of the Razorbill, only louder and deeper.

Distribution and habitat

The Great Auk was found in the cold North Atlantic coastal waters along the coasts of Canada, the northeastern United States, Norway, Greenland, Iceland, Ireland, Great Britain, France, and northern Spain. The Great Auk left the North Atlantic waters for land only in order to breed, even roosting at sea when not breeding. The rookeries of the Great Auk were found from Baffin Bay down to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, across the far northern Atlantic, including Iceland, and in Norway and the British Isles in Europe. The Great Auk's nesting colonies required rocky islands with sloping shorelines to provide the birds access to the seashore. This was an extremely limiting factor and it is believed that the Great Auk may never have had more than 20 breeding colonies. Additionally, the nesting sites needed to be close to rich feeding areas and be far enough from the mainland to discourage visitation by humans and Polar Bears. Only seven breeding colonies are known: Papa Westray in the Orkney Islands, St. Kilda Island off Scotland, the Faeroe Islands between Iceland and Ireland, Grimsey Island and Eldey Island near Iceland, Funk Island near Newfoundland, and the Bird Rocks (Rochers-aux-Oiseaux) in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Records suggest that this species may have bred on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the breeding range of the Great Auk was restricted to Funk Island, Grimsey Island, Eldey Island, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and St. Kilda Island. Funk Island was the largest known breeding colony.

The Great Auk migrated north and south away from the breeding colonies after the chicks fledged and tended to go southward during late fall and winter. It was common in the Grand Banks. Its bones have been found as far south as Florida, where it may have occurred during four isolated time periods: around 1000 BC, 1000 AD, the 15th century, and the 17th century. It also frequented France, Spain, and even Italy in the Mediterranean Sea. The Great Auk typically did not go further south than Massachusetts Bay in the winter. Additionally, it has been suggested that some of the bones discovered in Florida may be the result of aboriginal trading.

Ecology and behavior

Great Auks walked slowly and sometimes used their wings to help them traverse rough terrain. When they did run, it was awkwardly and with short steps in a straight line. They had few natural predators, mainly large marine mammals, such as the Orca, and White-tailed Eagles., Polar Bears preyed on nesting colonies of the auk. This species had no innate fear of human beings, and their flightlessness and awkwardness on land compounded their vulnerability. They were hunted for food, feathers, and as specimens for museums and private collections. Great Auks reacted to noises, but were rarely scared by the sight of something. The auks used their bills aggressively both in the dense nesting sites and when threatened or captured by humans. These birds are believed to have had a life span of about 20 to 25 years. During the winter, the Great Auk migrated south either in pairs or in small groups, and never with the entire nesting colony.

The Great Auk was generally an excellent swimmer, using its wings to propel itself underwater. While swimming, the head was held up but the neck was drawn in. This species was capable of banking, veering, and turning underwater. The Great Auk was known to dive to depths of 76 metres (249 ft) and it has been claimed that the species was able to dive to depths of 1 kilometre (3,300 ft). It could also hold its breath for 15 minutes, longer than a seal. The Great Auk was capable of swimming rapidly to gather speed, then shooting out of the water and landing on a rocky ledge above the ocean's surface.

Diet

This alcid typically fed in shoaling waters which were shallower than those frequented by other alcids, although after the breeding season they had been sighted up to 500 kilometres (310 mi) from land. They are believed to have fed cooperatively in flocks. Their main food was fish, usually 12 to 20 centimetres (4.7 to 7.9 in) in length and weighing 40 to 50 grams (1.4 to 1.8 oz), but occasionally their prey was up to half the bird's own length. The bird could on average dive up to 75 metres (246 ft) for its prey with the maximum dive depth being estimated at 130 metres (430 ft); however, to conserve energy, most dives were shallower. Its ability to dive so deep reduced competition with other alcid species. Based on remains associated with Great Auk bones found on Funk Island and on ecological and morphological considerations, it seems that Atlantic Menhaden and Capelin were their favored prey. Other fish suggested as potential prey include lumpsuckers, Shorthorn Sculpins, cod, crustaceans, and sand lance. The young of the Great Auk are believed to have eaten plankton and, possibly, fish and crustaceans regurgitated by adult auks.

Reproduction

Great Auks began pairing in early and mid May. They are believed to have mated for life, although some theorize that auks could have mated outside of their pair, a trait seen in the Razorbill. Once paired, they nested at the base of cliffs in colonies, where they likely copulated. Mated pairs had a social display in which they bobbed their heads, showing off their white eye patch, bill markings, and yellow mouth. These colonies were extremely crowded and dense, with some estimates stating that there was a nesting auk for every 1 square metre (11 sq ft) of land. These colonies were very social. When the colonies included other species of alcid, the Great Auks were dominant due to their size.

The Great Auk laid only one egg each year between late May and early June, though they could lay a replacement egg if the first one was lost. In years when there was a shortage of food, the auk did not breed. The species laid a single egg on bare ground up to 100 metres (330 ft) from shore. The egg was pear-shaped and averaged 12.4 centimetres (4.9 in) in length and 7.6 centimetres (3.0 in) across at the widest point. The egg was yellowish white to light ochre with a varying pattern of black, brown or greyish spots and lines which often congregated on the large end. It is believed that the variation in the egg's streaks enabled the parents to recognize their egg in the colony. The pair took turns incubating the egg in an upright position for the 39 to 44 days before the egg hatched, typically in June, although eggs could be present at the colonies as late as August.

The parents also took turns feeding their chick. At birth, the chick was covered with grey down. The young bird took only two or three weeks to mature enough to abandon the nest and land for the water, typically around the middle of July. The parents cared for their young after they fledged, and adults were seen swimming with their young on their back. Great Auks sexually matured when they were four to seven years old.

Relationship with humans

The Great Auk is known to have been preyed upon by Neanderthals more than 100,000 years ago, as evidenced by well-cleaned bones found by their campfires. Images of the Great Auk were also carved into the walls of the El Pinto Cave in Spain over 35,000 years ago, while cave paintings 20,000 years old have been found in France's Grotte Cosquer.

Native Americans who coexisted with the Great Auk valued it as a food source during the winter and as an important symbol. Images of the Great Auk have been found in bone necklaces. A person buried at the Maritime Archaic site at Port au Choix, Newfoundland, dating to about 2000 BC, was interred clothed in a suit made from more than 200 Great Auk skins, with the heads left attached as decoration. Nearly half of the bird bones found in graves at this site were of the Great Auk, suggesting that it had cultural significance for the Maritime Archaic people. The extinct Beothuks of Newfoundland made pudding out of the auk's eggs. The Dorset Eskimos also hunted the species, while the Saqqaq in Greenland overhunted the species, causing a range reduction locally.

Later, European sailors used the auks as a navigational beacon, as the presence of these birds signaled that the Grand Banks of Newfoundland were near.

Extinction

This species is estimated to have had a maximum population in the millions, although some scientists dispute this estimate. The Great Auk was hunted on a significant scale for food, eggs, and its down feathers from at least the 8th century. Prior to that, hunting by local natives can be documented from Late Stone Age Scandinavia and eastern North America, as well as from early 5th century Labrador, where the bird seems to have occurred only as a straggler. Early explorers, including Jacques Cartier and numerous ships attempting to find gold on Baffin Island, were not provisioned with food for the journey home, and therefore used this species as both a convenient food source and bait for fishing. Some of the later vessels anchored next to a colony and ran out planks to the land. The sailors then herded hundreds of these auks onto the ships, where they were then slaughtered. Some authors have questioned whether this hunting method actually occurred successfully. Great Auk eggs were also a valued food source, as the eggs were three times the size of a murre's and had a large yolk. These sailors also introduced rats onto the islands.

The Little Ice Age may have reduced the population of the Great Auk by exposing more of their breeding islands to predation by Polar Bears, but massive exploitation for their down drastically reduced the population. By the mid-16th century, the nesting colonies along the European side of the Atlantic were nearly all eliminated by humans killing this bird for its down, which was used to make pillows. In 1553, the auk received its first official protection, and in 1794 Great Britain banned the killing of this species for its feathers. In St. John's, individuals violating a 1775 law banning hunting the Great Auk for its feathers or eggs were publicly flogged, though hunting for use as fishing bait was still permitted. On the North American side, eider down was initially preferred, but once the eiders were nearly driven to extinction in the 1770s, down collectors switched to the auk at the same time that hunting for food, fishing bait, and oil decreased. Specimens of the Great Auk and its eggs became collectible and highly prized by rich Europeans, and the loss of a large number of its eggs to collection contributed to the demise of the species. Eggers, individuals who visited the nesting sites of the Great Auk to collect their eggs, quickly realized that the birds did not all lay their eggs on the same day, so they could make return visits to the same breeding colony. Eggers only collected eggs without embryos growing inside of them and typically discarded the eggs with embryos.

It was on the islet of Stac an Armin, St Kilda, Scotland, in July 1840, that the last Great Auk seen in the British Isles was caught and killed. Three men from St Kilda caught a single "garefowl", noticing its little wings and the large white spot on its head. They tied it up and kept it alive for three days, until a large storm arose. Believing that the auk was a witch and the cause of the storm, they then killed it by beating it with a stick.

The last colony of Great Auks lived on Geirfuglasker (the "Great Auk Rock") off Iceland. This islet was a volcanic rock surrounded by cliffs which made it inaccessible to humans, but in 1830 the islet submerged after a volcanic eruption, and the birds moved to the nearby island of Eldey, which was accessible from a single side. When the colony was initially discovered in 1835, nearly fifty birds were present. Museums, desiring the skins of the auk for preservation and display, quickly began collecting birds from the colony. The last pair, found incubating an egg, was killed there on 3 July 1844, with Jón Brandsson and Sigurður Ísleifsson strangling the adults and Ketill Ketilsson smashing the egg with his boot. However, a later claim of a live individual sighted in 1852 on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland has been accepted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

Today, around 75 eggs of the Great Auk remain in museum collections, along with 24 complete skeletons and 81 mounted skins. While thousands of isolated bones have been collected from 19th century Funk Island to Neolithic middens, only a small number of complete skeletons exist. Following the bird's extinction, the price of its eggs sometimes reached up to 11 times the amount earned by a skilled worker in a year.

Did human hunting activities alone drive great auks' extinction?

by eLife

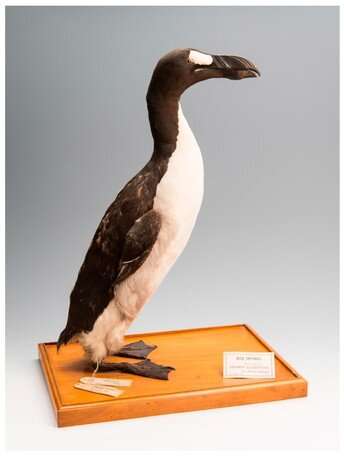

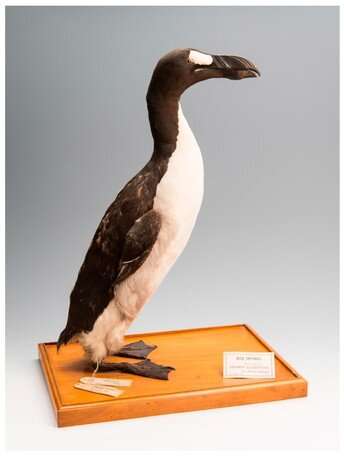

A mounted great auk skin, The Brussels Auk (RBINS 5355), from the collections at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS). Credit: Thierry Hubin, RBINS (CC BY 4.0)

New insight on the extinction history of a flightless seabird that vanished from the shores of the North Atlantic during the 19th century has been published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that intense hunting by humans could have caused the rapid extinction of the great auk, showing how even species that exist in large and widespread populations can be vulnerable to exploitation.

Great auks were large, flightless diving birds thought to have existed in the millions. They were distributed around the North Atlantic, with breeding colonies along the east coast of North America and especially on the islands off Newfoundland. They could also be found on islands off the coasts of Iceland and Scotland, as well as throughout Scandinavia.

But these birds had a long history of being hunted by humans. They were poached for their meat and eggs during prehistoric times, and this activity was further intensified in 1500 AD by European seamen visiting the fishing grounds of Newfoundland. Their feathers later became highly sought after in the 1700s, contributing further to their demise.

"Despite the well-documented history of exploitation since the 16th century, it is unclear whether hunting alone could have been responsible for the species' extinction, or whether the birds were already in decline due to natural environmental changes," says lead author Jessica Thomas, who completed the work as part of her Ph.D. studies at Bangor University, UK, and the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and is now a postdoctoral researcher at Swansea University, Wales, UK.

Great auk humeri from Funk Island. These samples are part of the great auk collection at the American Museum of Natural History. Credit: J. Thomas (CC BY 4.0)

To investigate this further, Thomas and her collaborators carried out combined analyses of ancient genetic data, GPS-based ocean current data, and population viability—a process that looks at the probability of a population going extinct within a given number of years. They sequenced complete mitochondrial genomes of 41 individuals from across the species' geographic range and used their analyses to reconstruct the birds' population structure and dynamics throughout the Holocene period, the last 11,700 years of Earth's history.

"Taken together, our data don't suggest that great auks were at risk of extinction prior to intensive human hunting behaviour in the early 16th century," explains co-senior author Thomas Gilbert, Professor of Evolutionary Genomics at the University of Copenhagen. "But critically, this doesn't mean that we've provided solid evidence that humans alone were the cause of great auk extinction. What we have demonstrated is that human hunting pressure was likely to have caused extinction even if the birds weren't already under threat from environmental changes."

Gilbert adds that their conclusions are limited by a couple of factors. The mitochondrial genome represents only a single genetic marker and, due to limited sample preservation and availability, the study sample size of 41 is relatively small for population genetic analyses.

"Despite these limitations, the findings help reveal how industrial-scale commercial exploitation of natural resources have the potential to drive an abundant, wide-ranging and genetically diverse species to extinction within a short period of time," says collaborator Gary Carvalho, Professor in Zoology (Molecular Ecology) at Bangor University. This echoes the conclusions of a previous study on the passenger pigeon, a bird that existed in significant numbers before going extinct in the early 20th century.

"Our work also emphasises the need to thoroughly monitor commercially harvested species, particularly in poorly researched environments such as our oceans," concludes co-senior author Michael Knapp, Senior Lecturer in Biological Anthropology and Rutherford Discovery Fellow at the University of Otago, New Zealand. "This will help lay the platform for sustainable ecosystems and ensure more effective conservation efforts."

phys.org/news/2019-11-human-great-auks-extinction.html

Journal Reference:

Jessica E Thomas et al, Demographic reconstruction from ancient DNA supports rapid extinction of the great auk, eLife (2019). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.47509

Abstract

The great auk was once abundant and distributed across the North Atlantic. It is now extinct, having been heavily exploited for its eggs, meat, and feathers. We investigated the impact of human hunting on its demise by integrating genetic data, GPS-based ocean current data, and analyses of population viability. We sequenced complete mitochondrial genomes of 41 individuals from across the species’ geographic range and reconstructed population structure and population dynamics throughout the Holocene. Taken together, our data do not provide any evidence that great auks were at risk of extinction prior to the onset of intensive human hunting in the early 16th century. In addition, our population viability analyses reveal that even if the great auk had not been under threat by environmental change, human hunting alone could have been sufficient to cause its extinction. Our results emphasise the vulnerability of even abundant and widespread species to intense and localised exploitation.

elifesciences.org/articles/47509

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

Genus: Pinguinus

Species: P. impennis

Conservation Status: Extinct

The Great Auk, Pinguinus impennis, formerly of the genus Alca, was a large, flightless alcid that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It was the only modern species in the genus Pinguinus, a group of birds that formerly included one other species of flightless giant auk from the Atlantic Ocean region. It bred on rocky, isolated islands with easy access to both the ocean and a plentiful food supply, a rarity in nature that provided only a few breeding sites for the auks. When not breeding, the auks spent their time foraging in the waters of the North Atlantic, ranging as far south as New England and northern Spain through Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Ireland, and Great Britain.

The Great Auk was 75 to 85 centimetres (30 to 33 in) tall and weighed around 5 kilograms (11 lb), making it the largest member of the alcid family. It had a black back and a white belly. The black beak was heavy and hooked with grooves etched into its surface. During the breeding season, the Great Auk had a white patch over each eye. After the breeding season, the auk lost this patch, instead developing a white band stretching between the eyes. The wings were 15 centimetres (5.9 in) long, rendering the bird flightless. Instead, the auk was a powerful swimmer, a trait that it used in hunting. Its favorite prey were fish, including Atlantic Menhaden and Capelin, and crustaceans. Although agile in the water, it was clumsy on land. Its main predators were Orcas, White-tailed Eagles, Polar Bears, and humans. Great Auk pairs mated for life. They nested in extremely dense and social colonies, laying one egg on bare rock. The egg was white with variable brown streaking. Both parents incubated for about six weeks before their young hatched. The young auks left the nest site after two or three weeks and the parents continued to care for them.

Humans had hunted the Great Auk for more than 100,000 years. It was an important part of many Native American cultures which coexisted with the bird, both as a food source and as a symbolic item. Many Maritime Archaic people were buried with Great Auk bones, and one was buried with a cloak made of over 200 auk skins. Early European explorers to the Americas used the auk as a convenient food source or as fishing bait, reducing its numbers. The bird's down was in high demand in Europe, a factor which largely eliminated the European populations by the mid-16th century. Scientists soon began to realize that the Great Auk was disappearing and it became the beneficiary of many early environmental laws, but this proved not to be enough. Its growing rarity increased interest from European museums and private collectors in obtaining skins and eggs of the bird. This trend eliminated the last of the Great Auks on 3 July 1844 on Eldey, Iceland. However, a record of a bird in 1852 is considered by some to be the last sighting of this species. The Great Auk is mentioned in a number of novels and the scientific journal of the American Ornithologists' Union is named The Auk in honor of this bird.

Taxonomy

The Great Auk was one of the 4400 animal species originally described by Carolus Linnaeus in his 18th century work, Systema Naturae, in which it was named Alca impennis. The species was not placed in its own genus, Pinguinus, until 1791. The generic name is derived from the Spanish and Portuguese name for the species, while the specific name impennis is from Latin and refers to the lack of flight feathers or pennae.

Analysis of mtDNA sequences have confirmed morphological and biogeographical studies in regarding the Razorbill as the Great Auk's closest living relative. The Great Auk was also closely related to the Little Auk (Dovekie), which underwent a radically different evolution compared to Pinguinus. Due to its outward similarity to the Razorbill (apart from flightlessness and size), the Great Auk was often placed in the genus Alca, following Linnaeus. The name Alca is a Latin derivative of the Scandinavian word for Razorbills and their relatives.

The fossil record (especially Pinguinus alfrednewtoni) and molecular evidence demonstrate that the three genera, while closely related, diverged soon after their common ancestor, a bird probably similar to a stout Xantus's Murrelet, had spread to the coasts of the Atlantic. By that time the murres, or Atlantic guillemots, had apparently already split off from the other Atlantic alcids. Razorbill-like birds were common in the Atlantic during the Pliocene, but the evolution of the Little Auk is sparsely documented. The molecular data are compatible with either view, but the weight of evidence suggests placing the Great Auk in a distinct genus. The Great Auk was not closely related to the other extinct genera of flightless alcids, Mancalla, Praemancalla, and Alcodes.

Pinguinus alfrednewtoni was a larger though also flightless member of the genus Pinguinus that lived during the Early Pliocene. Known from bones found in the Yorktown Formation of the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina, it is believed to have split along with the Great Auk from a common ancestor. Pinguinus alfrednewtoni lived in the western Atlantic while the Great Auk lived in the eastern Atlantic, but after the former died out after the Pliocene, the Great Auk replaced it.

The Basque name for the Great Auk is arponaz while the early French name was apponatz, both meaning "spearbill". The Norse called the Great Auk geirfugl, which means "spearbird". This has led to an alternative common name for the bird, "garefowl". Spanish and Portuguese sailors called the bird pingüinos. The Inuit name for the Great Auk was isarukitsck, which meant "little wing". The Welsh people referred to this species as "pingwen" (actually spelled "pengwyn" - lit. white head). When European explorers discovered what are today known as penguins in the Southern Hemisphere, they noticed their similar appearance to the Great Auk and named them after this bird, despite the fact that they are not related.

Description

Standing about 75 to 85 centimetres (30 to 33 in) tall and weighing around 5 kilograms (11 lb), the flightless Great Auk was the largest of both its family and the order Charadriiformes. The auks which lived further north averaged larger in size than the more southerly members of the species. Males and females were similar in plumage, although there is evidence for differences in size, particularly in the bill and femur length. The back was primarily a glossy black, while the stomach was white. The neck and legs were short, and the head and wings small. The auk appeared chubby due to a thick layer of fat necessary for warmth. During the breeding season, the Great Auk developed a wide white eye patch over the eye, which had a hazel or chestnut iris. After the breeding season the auk molted and lost this eye patch, which was replaced with a wide white band and a gray line of feathers which stretched from the eye to the ear. During the summer, the auk's chin and throat were blackish-brown, while the inside of the mouth was yellow. During the winter, this alcid molted and the throat became white. The bill was large at 11 centimetres (4.3 in) long and curved downwards at the top; the bill also had deep white grooves in both the upper and lower mandibles, up to seven on the upper mandible and twelve on the lower mandible in summer, though there were fewer in winter. The wings were only 15 centimetres (5.9 in) in length and the longest wing feathers were only 10 centimetres (3.9 in) long. Its feet and short claws were black while the webbed skin between the toes was brownish black. The legs were far back on the bird's body, which gave it powerful swimming and diving abilities.

Hatchlings were gray and downy. Juvenile birds had less prominent grooves in their beaks and had mottled white and black necks, while the eye spot found in adults was not present; instead, a gray line ran through the eyes (which still had the white eye ring) to just below the ears.

The auk's calls included low croaking and a hoarse scream. A captive auk was observed making a gurgling noise when anxious. It is not known what its other vocalizations were like, but it is believed that they were similar to those of the Razorbill, only louder and deeper.

Distribution and habitat

The Great Auk was found in the cold North Atlantic coastal waters along the coasts of Canada, the northeastern United States, Norway, Greenland, Iceland, Ireland, Great Britain, France, and northern Spain. The Great Auk left the North Atlantic waters for land only in order to breed, even roosting at sea when not breeding. The rookeries of the Great Auk were found from Baffin Bay down to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, across the far northern Atlantic, including Iceland, and in Norway and the British Isles in Europe. The Great Auk's nesting colonies required rocky islands with sloping shorelines to provide the birds access to the seashore. This was an extremely limiting factor and it is believed that the Great Auk may never have had more than 20 breeding colonies. Additionally, the nesting sites needed to be close to rich feeding areas and be far enough from the mainland to discourage visitation by humans and Polar Bears. Only seven breeding colonies are known: Papa Westray in the Orkney Islands, St. Kilda Island off Scotland, the Faeroe Islands between Iceland and Ireland, Grimsey Island and Eldey Island near Iceland, Funk Island near Newfoundland, and the Bird Rocks (Rochers-aux-Oiseaux) in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Records suggest that this species may have bred on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the breeding range of the Great Auk was restricted to Funk Island, Grimsey Island, Eldey Island, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and St. Kilda Island. Funk Island was the largest known breeding colony.

The Great Auk migrated north and south away from the breeding colonies after the chicks fledged and tended to go southward during late fall and winter. It was common in the Grand Banks. Its bones have been found as far south as Florida, where it may have occurred during four isolated time periods: around 1000 BC, 1000 AD, the 15th century, and the 17th century. It also frequented France, Spain, and even Italy in the Mediterranean Sea. The Great Auk typically did not go further south than Massachusetts Bay in the winter. Additionally, it has been suggested that some of the bones discovered in Florida may be the result of aboriginal trading.

Ecology and behavior

Great Auks walked slowly and sometimes used their wings to help them traverse rough terrain. When they did run, it was awkwardly and with short steps in a straight line. They had few natural predators, mainly large marine mammals, such as the Orca, and White-tailed Eagles., Polar Bears preyed on nesting colonies of the auk. This species had no innate fear of human beings, and their flightlessness and awkwardness on land compounded their vulnerability. They were hunted for food, feathers, and as specimens for museums and private collections. Great Auks reacted to noises, but were rarely scared by the sight of something. The auks used their bills aggressively both in the dense nesting sites and when threatened or captured by humans. These birds are believed to have had a life span of about 20 to 25 years. During the winter, the Great Auk migrated south either in pairs or in small groups, and never with the entire nesting colony.

The Great Auk was generally an excellent swimmer, using its wings to propel itself underwater. While swimming, the head was held up but the neck was drawn in. This species was capable of banking, veering, and turning underwater. The Great Auk was known to dive to depths of 76 metres (249 ft) and it has been claimed that the species was able to dive to depths of 1 kilometre (3,300 ft). It could also hold its breath for 15 minutes, longer than a seal. The Great Auk was capable of swimming rapidly to gather speed, then shooting out of the water and landing on a rocky ledge above the ocean's surface.

Diet

This alcid typically fed in shoaling waters which were shallower than those frequented by other alcids, although after the breeding season they had been sighted up to 500 kilometres (310 mi) from land. They are believed to have fed cooperatively in flocks. Their main food was fish, usually 12 to 20 centimetres (4.7 to 7.9 in) in length and weighing 40 to 50 grams (1.4 to 1.8 oz), but occasionally their prey was up to half the bird's own length. The bird could on average dive up to 75 metres (246 ft) for its prey with the maximum dive depth being estimated at 130 metres (430 ft); however, to conserve energy, most dives were shallower. Its ability to dive so deep reduced competition with other alcid species. Based on remains associated with Great Auk bones found on Funk Island and on ecological and morphological considerations, it seems that Atlantic Menhaden and Capelin were their favored prey. Other fish suggested as potential prey include lumpsuckers, Shorthorn Sculpins, cod, crustaceans, and sand lance. The young of the Great Auk are believed to have eaten plankton and, possibly, fish and crustaceans regurgitated by adult auks.

Reproduction

Great Auks began pairing in early and mid May. They are believed to have mated for life, although some theorize that auks could have mated outside of their pair, a trait seen in the Razorbill. Once paired, they nested at the base of cliffs in colonies, where they likely copulated. Mated pairs had a social display in which they bobbed their heads, showing off their white eye patch, bill markings, and yellow mouth. These colonies were extremely crowded and dense, with some estimates stating that there was a nesting auk for every 1 square metre (11 sq ft) of land. These colonies were very social. When the colonies included other species of alcid, the Great Auks were dominant due to their size.

The Great Auk laid only one egg each year between late May and early June, though they could lay a replacement egg if the first one was lost. In years when there was a shortage of food, the auk did not breed. The species laid a single egg on bare ground up to 100 metres (330 ft) from shore. The egg was pear-shaped and averaged 12.4 centimetres (4.9 in) in length and 7.6 centimetres (3.0 in) across at the widest point. The egg was yellowish white to light ochre with a varying pattern of black, brown or greyish spots and lines which often congregated on the large end. It is believed that the variation in the egg's streaks enabled the parents to recognize their egg in the colony. The pair took turns incubating the egg in an upright position for the 39 to 44 days before the egg hatched, typically in June, although eggs could be present at the colonies as late as August.

The parents also took turns feeding their chick. At birth, the chick was covered with grey down. The young bird took only two or three weeks to mature enough to abandon the nest and land for the water, typically around the middle of July. The parents cared for their young after they fledged, and adults were seen swimming with their young on their back. Great Auks sexually matured when they were four to seven years old.

Relationship with humans

The Great Auk is known to have been preyed upon by Neanderthals more than 100,000 years ago, as evidenced by well-cleaned bones found by their campfires. Images of the Great Auk were also carved into the walls of the El Pinto Cave in Spain over 35,000 years ago, while cave paintings 20,000 years old have been found in France's Grotte Cosquer.

Native Americans who coexisted with the Great Auk valued it as a food source during the winter and as an important symbol. Images of the Great Auk have been found in bone necklaces. A person buried at the Maritime Archaic site at Port au Choix, Newfoundland, dating to about 2000 BC, was interred clothed in a suit made from more than 200 Great Auk skins, with the heads left attached as decoration. Nearly half of the bird bones found in graves at this site were of the Great Auk, suggesting that it had cultural significance for the Maritime Archaic people. The extinct Beothuks of Newfoundland made pudding out of the auk's eggs. The Dorset Eskimos also hunted the species, while the Saqqaq in Greenland overhunted the species, causing a range reduction locally.

Later, European sailors used the auks as a navigational beacon, as the presence of these birds signaled that the Grand Banks of Newfoundland were near.

Extinction

This species is estimated to have had a maximum population in the millions, although some scientists dispute this estimate. The Great Auk was hunted on a significant scale for food, eggs, and its down feathers from at least the 8th century. Prior to that, hunting by local natives can be documented from Late Stone Age Scandinavia and eastern North America, as well as from early 5th century Labrador, where the bird seems to have occurred only as a straggler. Early explorers, including Jacques Cartier and numerous ships attempting to find gold on Baffin Island, were not provisioned with food for the journey home, and therefore used this species as both a convenient food source and bait for fishing. Some of the later vessels anchored next to a colony and ran out planks to the land. The sailors then herded hundreds of these auks onto the ships, where they were then slaughtered. Some authors have questioned whether this hunting method actually occurred successfully. Great Auk eggs were also a valued food source, as the eggs were three times the size of a murre's and had a large yolk. These sailors also introduced rats onto the islands.

The Little Ice Age may have reduced the population of the Great Auk by exposing more of their breeding islands to predation by Polar Bears, but massive exploitation for their down drastically reduced the population. By the mid-16th century, the nesting colonies along the European side of the Atlantic were nearly all eliminated by humans killing this bird for its down, which was used to make pillows. In 1553, the auk received its first official protection, and in 1794 Great Britain banned the killing of this species for its feathers. In St. John's, individuals violating a 1775 law banning hunting the Great Auk for its feathers or eggs were publicly flogged, though hunting for use as fishing bait was still permitted. On the North American side, eider down was initially preferred, but once the eiders were nearly driven to extinction in the 1770s, down collectors switched to the auk at the same time that hunting for food, fishing bait, and oil decreased. Specimens of the Great Auk and its eggs became collectible and highly prized by rich Europeans, and the loss of a large number of its eggs to collection contributed to the demise of the species. Eggers, individuals who visited the nesting sites of the Great Auk to collect their eggs, quickly realized that the birds did not all lay their eggs on the same day, so they could make return visits to the same breeding colony. Eggers only collected eggs without embryos growing inside of them and typically discarded the eggs with embryos.

It was on the islet of Stac an Armin, St Kilda, Scotland, in July 1840, that the last Great Auk seen in the British Isles was caught and killed. Three men from St Kilda caught a single "garefowl", noticing its little wings and the large white spot on its head. They tied it up and kept it alive for three days, until a large storm arose. Believing that the auk was a witch and the cause of the storm, they then killed it by beating it with a stick.

The last colony of Great Auks lived on Geirfuglasker (the "Great Auk Rock") off Iceland. This islet was a volcanic rock surrounded by cliffs which made it inaccessible to humans, but in 1830 the islet submerged after a volcanic eruption, and the birds moved to the nearby island of Eldey, which was accessible from a single side. When the colony was initially discovered in 1835, nearly fifty birds were present. Museums, desiring the skins of the auk for preservation and display, quickly began collecting birds from the colony. The last pair, found incubating an egg, was killed there on 3 July 1844, with Jón Brandsson and Sigurður Ísleifsson strangling the adults and Ketill Ketilsson smashing the egg with his boot. However, a later claim of a live individual sighted in 1852 on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland has been accepted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

Today, around 75 eggs of the Great Auk remain in museum collections, along with 24 complete skeletons and 81 mounted skins. While thousands of isolated bones have been collected from 19th century Funk Island to Neolithic middens, only a small number of complete skeletons exist. Following the bird's extinction, the price of its eggs sometimes reached up to 11 times the amount earned by a skilled worker in a year.

Did human hunting activities alone drive great auks' extinction?

by eLife

A mounted great auk skin, The Brussels Auk (RBINS 5355), from the collections at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS). Credit: Thierry Hubin, RBINS (CC BY 4.0)

New insight on the extinction history of a flightless seabird that vanished from the shores of the North Atlantic during the 19th century has been published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that intense hunting by humans could have caused the rapid extinction of the great auk, showing how even species that exist in large and widespread populations can be vulnerable to exploitation.

Great auks were large, flightless diving birds thought to have existed in the millions. They were distributed around the North Atlantic, with breeding colonies along the east coast of North America and especially on the islands off Newfoundland. They could also be found on islands off the coasts of Iceland and Scotland, as well as throughout Scandinavia.

But these birds had a long history of being hunted by humans. They were poached for their meat and eggs during prehistoric times, and this activity was further intensified in 1500 AD by European seamen visiting the fishing grounds of Newfoundland. Their feathers later became highly sought after in the 1700s, contributing further to their demise.

"Despite the well-documented history of exploitation since the 16th century, it is unclear whether hunting alone could have been responsible for the species' extinction, or whether the birds were already in decline due to natural environmental changes," says lead author Jessica Thomas, who completed the work as part of her Ph.D. studies at Bangor University, UK, and the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and is now a postdoctoral researcher at Swansea University, Wales, UK.

Great auk humeri from Funk Island. These samples are part of the great auk collection at the American Museum of Natural History. Credit: J. Thomas (CC BY 4.0)

To investigate this further, Thomas and her collaborators carried out combined analyses of ancient genetic data, GPS-based ocean current data, and population viability—a process that looks at the probability of a population going extinct within a given number of years. They sequenced complete mitochondrial genomes of 41 individuals from across the species' geographic range and used their analyses to reconstruct the birds' population structure and dynamics throughout the Holocene period, the last 11,700 years of Earth's history.

"Taken together, our data don't suggest that great auks were at risk of extinction prior to intensive human hunting behaviour in the early 16th century," explains co-senior author Thomas Gilbert, Professor of Evolutionary Genomics at the University of Copenhagen. "But critically, this doesn't mean that we've provided solid evidence that humans alone were the cause of great auk extinction. What we have demonstrated is that human hunting pressure was likely to have caused extinction even if the birds weren't already under threat from environmental changes."

Gilbert adds that their conclusions are limited by a couple of factors. The mitochondrial genome represents only a single genetic marker and, due to limited sample preservation and availability, the study sample size of 41 is relatively small for population genetic analyses.

"Despite these limitations, the findings help reveal how industrial-scale commercial exploitation of natural resources have the potential to drive an abundant, wide-ranging and genetically diverse species to extinction within a short period of time," says collaborator Gary Carvalho, Professor in Zoology (Molecular Ecology) at Bangor University. This echoes the conclusions of a previous study on the passenger pigeon, a bird that existed in significant numbers before going extinct in the early 20th century.

"Our work also emphasises the need to thoroughly monitor commercially harvested species, particularly in poorly researched environments such as our oceans," concludes co-senior author Michael Knapp, Senior Lecturer in Biological Anthropology and Rutherford Discovery Fellow at the University of Otago, New Zealand. "This will help lay the platform for sustainable ecosystems and ensure more effective conservation efforts."

phys.org/news/2019-11-human-great-auks-extinction.html

Journal Reference:

Jessica E Thomas et al, Demographic reconstruction from ancient DNA supports rapid extinction of the great auk, eLife (2019). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.47509

Abstract

The great auk was once abundant and distributed across the North Atlantic. It is now extinct, having been heavily exploited for its eggs, meat, and feathers. We investigated the impact of human hunting on its demise by integrating genetic data, GPS-based ocean current data, and analyses of population viability. We sequenced complete mitochondrial genomes of 41 individuals from across the species’ geographic range and reconstructed population structure and population dynamics throughout the Holocene. Taken together, our data do not provide any evidence that great auks were at risk of extinction prior to the onset of intensive human hunting in the early 16th century. In addition, our population viability analyses reveal that even if the great auk had not been under threat by environmental change, human hunting alone could have been sufficient to cause its extinction. Our results emphasise the vulnerability of even abundant and widespread species to intense and localised exploitation.

elifesciences.org/articles/47509