Post by Eaglehawk on Nov 20, 2019 7:58:01 GMT

Arctic Tern - Sterna paradisaea

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Sternidae

Genus: Sterna

Species: Sterna paradisaea

The Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) is a seabird of the tern family Sternidae. This bird has a circumpolar distribution, breeding colonially in Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Europe, Asia, and North America (as far south as Brittany and Massachusetts). The species is strongly migratory, seeing two summers each year as it migrates from its northern breeding grounds to the oceans around Antarctica and back (about 24,000 miles) each year. This is the longest regular migration by any known animal. The arctic tern flies as well as glides through the air, performing almost all of its tasks in the air. The arctic tern lands once every one to three years (depending on their mating cycle) to nest; once they have finished nesting they take to the sky for another long southern migration.

Arctic Terns are medium-sized birds. They have a length of 33–39 cm (13–15 in) and a wingspan of 76–85 cm (26–30 in). They are mainly grey and white plumaged, with a red beak (as long as the head, straight, with pronounced gonys) and feet, white forehead, a black nape and crown (streaked white), and white cheeks. The grey mantle is 305 mm, and the scapulars are fringed brown, some tipped white. The upper wing is grey with a white leading edge, and the collar is completely white, as is the rump. The deeply forked tail is whitish, with grey outer webs. The hindcrown to the ear-coverts is black.

Arctic Terns are long-lived birds, with many reaching thirty years of age. They eat mainly fish and small marine invertebrates. The species is abundant, with an estimated one million individuals. While the trend in the number of individuals in the species as a whole is not known, exploitation in the past has reduced this bird's numbers in the southern reaches of its range.

Distribution and migration

The Arctic Tern has a worldwide, circumpolar breeding distribution which is continuous; there are no recognized subspecies. It can be found in coastal regions in cooler temperate parts of North America and Eurasia during the northern summer. While wintering during the southern summer, it can be found at sea, reaching the southern edge of the Antarctic ice. The species' range encompasses an area of approximately ten million square kilometers.

The Arctic Tern is famous for its migration; it flies from its Arctic breeding grounds to the Antarctic and back again each year. This 19,000 km (12,000 mi) journey each way ensures that this bird sees two summers per year and more daylight than any other creature on the planet. The average Arctic Tern in its life will travel a distance equal to going to the moon and back—about 500,000 miles (800,000 km). One example of this bird's remarkable long-distance flying abilities involves an Arctic Tern ringed as an unfledged chick on the Farne Islands, Northumberland, UK, in summer 1982, which reached Melbourne, Australia, in October 1982, a sea journey of over 22,000 km (14,000 mi) in just three months from fledging. Another example is that of a chick ringed in Labrador, Canada, on 23 July 1928. It was found in South Africa four months later.

Arctic Terns usually migrate far offshore. Consequently, they are rarely seen from land outside the breeding season.

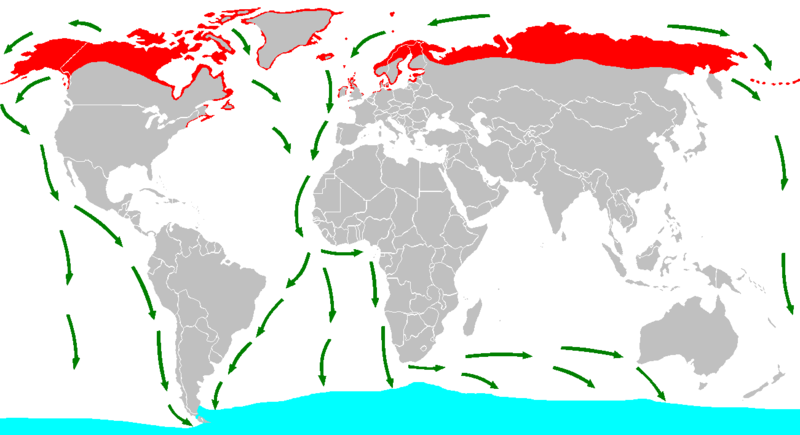

Breeding grounds (red), wintering grounds (blue) and migration routes (green)

Description and taxonomy

The Arctic Tern is a medium-sized bird around 33–36 cm (13–15 in) from the tip of its beak to the tip of its tail. The wingspan is 76–85 cm. The weight is 86–127 g (3.0–4.5 oz). The beak is dark red, as are the short legs and webbed feet. Like most terns, the Arctic Tern has high aspect ratio wings and a tail with a deep fork.

The adult plumage is grey above, with a black nape and crown and white cheeks. The upperwings are pale grey, with the area near the wingtip being translucent. The tail is white, and the underparts pale grey. Both sexes are similar in appearance. The winter plumage is similar, but the crown is whiter and the bills are darker.

Juveniles differ from adults in their black bill and legs, "scaly" appearing wings, and mantle with dark feather tips, dark carpal wing bar, and short tail streamers. During their first summer, juveniles also have a whiter forecrown.

The species has a variety of calls; the two most common being the alarm call, made when possible predators (such as humans or other mammals) enter the colonies, and the advertising call. The advertising call is social in nature, made when returning to the colony and during aggressive encounters between individuals. It is unique to each individual tern and as such it serves a similar role to the bird song of passerines, identifying individuals. Eight other calls have been described, from begging calls made by females during mating to attack calls made while swooping at intruders.

While the Arctic Tern is similar to the Common and Roseate Terns, its colouring, profile, and call are slightly different. Compared to the Common Tern, it has a longer tail and mono-coloured bill, while the main differences from the Roseate are its slightly darker colour and longer wings. The Arctic Tern's call is more nasal and rasping than that of the Common, and is easily distinguishable from that of the Roseate.

This bird's closest relatives are a group of South Polar species, the South American (Sterna hirundinacea), Kerguelen (S. virgata), and Antarctic (S. vittata) Terns. On the wintering grounds, the Arctic Tern can be distinguished from these relatives; the six-month difference in moult is the best clue here, with Arctic Terns being in winter plumage during the southern summer. The southern species also do not show darker wingtips in flight.

Reproduction

Breeding begins around the third or fourth year. Arctic Terns mate for life, and in most cases, return to the same colony each year. Courtship is elaborate, especially in birds nesting for the first time. Courtship begins with a so-called "high flight", where a female will chase the male to a high altitude and then slowly descend. This display is followed by "fish flights", where the male will offer fish to the female. Courtship on the ground involves strutting with a raised tail and lowered wings. After this, both birds will usually fly and circle each other.

Both sexes agree on a site for a nest, and both will defend the site. During this time, the male continues to feed the female. Mating occurs shortly after this. Breeding takes place in colonies on coasts, islands and occasionally inland on tundra near water. It often forms mixed flocks with the Common Tern. It lays from one to three eggs per clutch, most often two.

It is one of the most aggressive terns, fiercely defensive of its nest and young. It will attack humans and large predators, usually striking the top or back of the head. Although it is too small to cause serious injury, it is still capable of drawing blood. Other birds can benefit from nesting in an area defended by Arctic Terns.

The nest is usually a depression in the ground, which may or may not be lined with bits of grass or similar materials. The eggs are mottled and camouflaged. Both sexes share incubation duties. The young hatch after 22–27 days and fledge after 21–24 days. If the parents are disturbed and flush from the nest frequently the incubation period could be extended to as long as 34 days.

When hatched, the chicks are downy. Neither altricial nor precocial, the chicks begin to move around and explore their surroundings within one to three days after hatching. Usually, they do not stray far from the nest.

Chicks are brooded by the adults for the first ten days after hatching. Both parents care for hatchlings. Chick diets always include fish, and parents selectively bring larger prey items to chicks than they eat themselves. Males bring more food than females. Feeding by the parents lasts for roughly a month before being weaned off slowly. After fledging, the juveniles learn to feed themselves, including the difficult method of plunge-diving. They will fly south to winter with the help of their parents.

Arctic Sterns are long-lived birds that spend considerable time raising only a few young, and are thus said to be K-selected. The maximum recorded lifespan for the species is 34 years. A lifespan of twenty years may not be unusual, with a study in the Farne Islands estimating an annual survival rate of 82%.

Ecology and behaviour

The diet of the Arctic Tern varies depending on location and time, but is usually carnivorous. In most cases, it eats small fish or marine crustaceans. Fish species comprise the most important part of the diet, and account for more of the biomass consumed than any other food. Prey species are immature (1–2 year old) shoaling species such as herring, cod, sandlances, and capelin. Among the marine crustaceans eaten are amphipods, crabs and krill. Sometimes, these birds also eat molluscs, marine worms, or berries, and on their northern breeding grounds, insects.

Arctic Terns sometimes dip down to the surface of the water to catch prey close to the surface. They may also chase insects in the air when breeding. It is also thought that Arctic Terns may, in spite of their small size, occasionally engage in kleptoparasitism by swooping at birds so as to startle them into releasing their catches. Several species are targeted—conspecifics, other terns (like the Common Tern), and some auk and grebe species.

While nesting, Arctic Terns are vulnerable to predation by cats and other animals. Besides being a competitor for nesting sites, the larger Herring Gull steals eggs and hatchlings. Camouflaged eggs help prevent this, as do isolated nesting sites. While feeding, skuas, gulls, and other tern species will often harass the birds and steal their food. They often form mixed colonies with other terns, such as Common and Sandwich Terns.

Conservation status

Arctic Terns are considered threatened or species of concern in certain states. They are also among the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds applies. The species declined in New England in the late nineteenth-century due to hunting for the millinery trade. Exploitation continues today in western Greenland, where the species has declined greatly since 1950.

At the southern part of their range, the Arctic Tern has been declining in numbers. Much of this is due to shortages of food. However, most of these birds' range is extremely remote, with no apparent trend in the species as a whole.

Birdlife International has considered the species to be at lower risk since 1988, believing that there are approximately one million individuals around the world.

First evidence of the impact of climate change on Arctic Terns

by Newcastle University

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Data collected from electronic tags retrieved from 47 journeys made by the Farne Island Arctic Terns, has revealed for the first time how climate change might affect their behaviour.

Arctic Terns spend their breeding and non-breeding seasons in polar environments at opposite ends of the world and are our longest-migrating seabird.

Spending their non-breeding season in the Antarctic, the remoteness of this part of the world means that until now we have had a very limited understanding of their behaviour and distribution while they are there.

Analysing the data from 47 migrations over two study years, 2015 and 2017, the team found:

Dr. Chris Redfern, of Newcastle University, UK, who has led the study explained:

"Sea ice is an important habitat for juvenile krill as it provides protection from predators and from the intense light of the Antarctic summer.

"We now know that krill are the main food source for the Terns so it seems likely the warmer weather during 2016/2017 led to reduced krill abundance and so the birds were forced to forage in different areas.

"And in fact, in that second year, the birds converged on the Shackleton Ice Shelf rather than being spread out along the East Antarctica coastline.

"Polar regions are particularly sensitive to climate change and even small shifts can have major implications throughout the entire food web.

"This is why it is critical to understand how seabirds such as the Arctic Terns are affected by environmental change, both short and long term."

Co-author Professor Richard Bevan, of Newcastle University, adds:

"In the course of this study, we have been continuously amazed by the incredible journeys that these seabirds make each year and now we are beginning to get a glimpse into what they are doing in their wintering areas in Antarctica.

"Arctic Terns are one of the few non-breeding birds that are present in Antarctic waters during the summer. This means the birds are not constrained to a nest site but can move to where the best feeding sites are located.

"By following the journeys made by these birds, we can monitor changes in the location of these hot spots and get some insight into environmental changes that are taking place in these very remote locations; areas to which few scientists ever venture or monitor."

The data were collected as part of a landmark study led by Newcastle University in collaboration with the National Trust, BBC Springwatch and the Natural History Society of Northumbria.

The first data retrieved from the study highlighted the incredible journey travelled by these seabirds, with one flying an estimated 96,000Km (almost 60,000 miles) from its breeding grounds on the Farne Islands, off the Northumberland coast, to its winter quarters in Antarctica.

Mapping in unprecedented detail the route and stop-off points from the Farnes to Antarctica for the winter and back again to breed, the team tracked:

"The Arctic Tern's dependence on the ice throughout their non-breeding period in Antarctica highlights the vulnerability of the species to climate change," says Dr. Redfern.

"It is well known that Arctic Terns have relatively shorter legs than other tern species and in light of what we now know, this may be an adaptation to life associated with low temperatures—the freezing point of sea water is -1.8 C and the daily average minimum temperatures recorded by the birds' data loggers was between 0 to -5 C.

"The trackers have given us a unique glimpse into the lives of these incredible birds, surviving against all the odds, and highlights how precarious their future is in the light of anthropogenic climate change."

phys.org/news/2019-11-evidence-impact-climate-arctic-terns.html

Journal Reference:

Chris P. F. Redfern et al, Use of sea ice by arctic terns Sterna paradisaea in Antarctica and impacts of climate change, Journal of Avian Biology (2019). DOI: 10.1111/jav.02318

Abstract

Arctic Terns spend their breeding and non‐breeding seasons in polar environments at opposite ends of the world. The sensitivity of polar regions to climate change makes it essential to understand the ecology of Arctic Terns but the remoteness of the Antarctic presents a considerable challenge. One solution is to use ‘biologgers’ to monitor remotely their behaviour and distribution in the Antarctic. Data from birds tagged with light‐level global location sensors (geolocators) in 2015 and 2017 showed that a third of their annual cycle was spent amongst Antarctic sea ice. After reaching the East Antarctic in the austral spring, they gradually moved west, foraging in fragmented ice zones of the Antarctic coastline, leaving in the austral autumn for their return northward migration via the Atlantic. Changes in patterns of movement between phases of 24‐h daylight and diel day/night conditions were likely linked to the annual moult, and stable isotope analyses suggest that krill (Euphausia species) was an important component of their diet. There were marked differences in movement behaviour between Arctic Terns tagged in 2015 compared to 2017 that may relate to unusual changes in sea‐ice extent. The Arctic Tern may be unique amongst seabirds that utilise the Antarctic environment in summer in being able to move widely without nesting constraints, and may present a means of characterising the effects of climate change on species dependent for foraging on Antarctic sea‐ice and krill.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jav.02318

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Sternidae

Genus: Sterna

Species: Sterna paradisaea

The Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) is a seabird of the tern family Sternidae. This bird has a circumpolar distribution, breeding colonially in Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Europe, Asia, and North America (as far south as Brittany and Massachusetts). The species is strongly migratory, seeing two summers each year as it migrates from its northern breeding grounds to the oceans around Antarctica and back (about 24,000 miles) each year. This is the longest regular migration by any known animal. The arctic tern flies as well as glides through the air, performing almost all of its tasks in the air. The arctic tern lands once every one to three years (depending on their mating cycle) to nest; once they have finished nesting they take to the sky for another long southern migration.

Arctic Terns are medium-sized birds. They have a length of 33–39 cm (13–15 in) and a wingspan of 76–85 cm (26–30 in). They are mainly grey and white plumaged, with a red beak (as long as the head, straight, with pronounced gonys) and feet, white forehead, a black nape and crown (streaked white), and white cheeks. The grey mantle is 305 mm, and the scapulars are fringed brown, some tipped white. The upper wing is grey with a white leading edge, and the collar is completely white, as is the rump. The deeply forked tail is whitish, with grey outer webs. The hindcrown to the ear-coverts is black.

Arctic Terns are long-lived birds, with many reaching thirty years of age. They eat mainly fish and small marine invertebrates. The species is abundant, with an estimated one million individuals. While the trend in the number of individuals in the species as a whole is not known, exploitation in the past has reduced this bird's numbers in the southern reaches of its range.

Distribution and migration

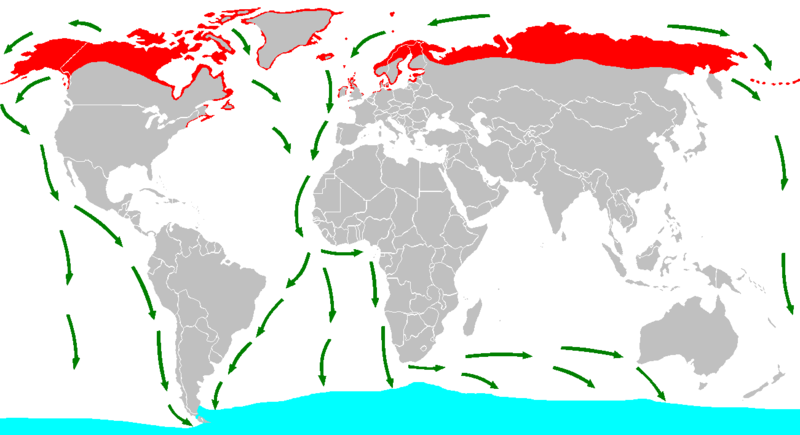

The Arctic Tern has a worldwide, circumpolar breeding distribution which is continuous; there are no recognized subspecies. It can be found in coastal regions in cooler temperate parts of North America and Eurasia during the northern summer. While wintering during the southern summer, it can be found at sea, reaching the southern edge of the Antarctic ice. The species' range encompasses an area of approximately ten million square kilometers.

The Arctic Tern is famous for its migration; it flies from its Arctic breeding grounds to the Antarctic and back again each year. This 19,000 km (12,000 mi) journey each way ensures that this bird sees two summers per year and more daylight than any other creature on the planet. The average Arctic Tern in its life will travel a distance equal to going to the moon and back—about 500,000 miles (800,000 km). One example of this bird's remarkable long-distance flying abilities involves an Arctic Tern ringed as an unfledged chick on the Farne Islands, Northumberland, UK, in summer 1982, which reached Melbourne, Australia, in October 1982, a sea journey of over 22,000 km (14,000 mi) in just three months from fledging. Another example is that of a chick ringed in Labrador, Canada, on 23 July 1928. It was found in South Africa four months later.

Arctic Terns usually migrate far offshore. Consequently, they are rarely seen from land outside the breeding season.

Breeding grounds (red), wintering grounds (blue) and migration routes (green)

Description and taxonomy

The Arctic Tern is a medium-sized bird around 33–36 cm (13–15 in) from the tip of its beak to the tip of its tail. The wingspan is 76–85 cm. The weight is 86–127 g (3.0–4.5 oz). The beak is dark red, as are the short legs and webbed feet. Like most terns, the Arctic Tern has high aspect ratio wings and a tail with a deep fork.

The adult plumage is grey above, with a black nape and crown and white cheeks. The upperwings are pale grey, with the area near the wingtip being translucent. The tail is white, and the underparts pale grey. Both sexes are similar in appearance. The winter plumage is similar, but the crown is whiter and the bills are darker.

Juveniles differ from adults in their black bill and legs, "scaly" appearing wings, and mantle with dark feather tips, dark carpal wing bar, and short tail streamers. During their first summer, juveniles also have a whiter forecrown.

The species has a variety of calls; the two most common being the alarm call, made when possible predators (such as humans or other mammals) enter the colonies, and the advertising call. The advertising call is social in nature, made when returning to the colony and during aggressive encounters between individuals. It is unique to each individual tern and as such it serves a similar role to the bird song of passerines, identifying individuals. Eight other calls have been described, from begging calls made by females during mating to attack calls made while swooping at intruders.

While the Arctic Tern is similar to the Common and Roseate Terns, its colouring, profile, and call are slightly different. Compared to the Common Tern, it has a longer tail and mono-coloured bill, while the main differences from the Roseate are its slightly darker colour and longer wings. The Arctic Tern's call is more nasal and rasping than that of the Common, and is easily distinguishable from that of the Roseate.

This bird's closest relatives are a group of South Polar species, the South American (Sterna hirundinacea), Kerguelen (S. virgata), and Antarctic (S. vittata) Terns. On the wintering grounds, the Arctic Tern can be distinguished from these relatives; the six-month difference in moult is the best clue here, with Arctic Terns being in winter plumage during the southern summer. The southern species also do not show darker wingtips in flight.

Reproduction

Breeding begins around the third or fourth year. Arctic Terns mate for life, and in most cases, return to the same colony each year. Courtship is elaborate, especially in birds nesting for the first time. Courtship begins with a so-called "high flight", where a female will chase the male to a high altitude and then slowly descend. This display is followed by "fish flights", where the male will offer fish to the female. Courtship on the ground involves strutting with a raised tail and lowered wings. After this, both birds will usually fly and circle each other.

Both sexes agree on a site for a nest, and both will defend the site. During this time, the male continues to feed the female. Mating occurs shortly after this. Breeding takes place in colonies on coasts, islands and occasionally inland on tundra near water. It often forms mixed flocks with the Common Tern. It lays from one to three eggs per clutch, most often two.

It is one of the most aggressive terns, fiercely defensive of its nest and young. It will attack humans and large predators, usually striking the top or back of the head. Although it is too small to cause serious injury, it is still capable of drawing blood. Other birds can benefit from nesting in an area defended by Arctic Terns.

The nest is usually a depression in the ground, which may or may not be lined with bits of grass or similar materials. The eggs are mottled and camouflaged. Both sexes share incubation duties. The young hatch after 22–27 days and fledge after 21–24 days. If the parents are disturbed and flush from the nest frequently the incubation period could be extended to as long as 34 days.

When hatched, the chicks are downy. Neither altricial nor precocial, the chicks begin to move around and explore their surroundings within one to three days after hatching. Usually, they do not stray far from the nest.

Chicks are brooded by the adults for the first ten days after hatching. Both parents care for hatchlings. Chick diets always include fish, and parents selectively bring larger prey items to chicks than they eat themselves. Males bring more food than females. Feeding by the parents lasts for roughly a month before being weaned off slowly. After fledging, the juveniles learn to feed themselves, including the difficult method of plunge-diving. They will fly south to winter with the help of their parents.

Arctic Sterns are long-lived birds that spend considerable time raising only a few young, and are thus said to be K-selected. The maximum recorded lifespan for the species is 34 years. A lifespan of twenty years may not be unusual, with a study in the Farne Islands estimating an annual survival rate of 82%.

Ecology and behaviour

The diet of the Arctic Tern varies depending on location and time, but is usually carnivorous. In most cases, it eats small fish or marine crustaceans. Fish species comprise the most important part of the diet, and account for more of the biomass consumed than any other food. Prey species are immature (1–2 year old) shoaling species such as herring, cod, sandlances, and capelin. Among the marine crustaceans eaten are amphipods, crabs and krill. Sometimes, these birds also eat molluscs, marine worms, or berries, and on their northern breeding grounds, insects.

Arctic Terns sometimes dip down to the surface of the water to catch prey close to the surface. They may also chase insects in the air when breeding. It is also thought that Arctic Terns may, in spite of their small size, occasionally engage in kleptoparasitism by swooping at birds so as to startle them into releasing their catches. Several species are targeted—conspecifics, other terns (like the Common Tern), and some auk and grebe species.

While nesting, Arctic Terns are vulnerable to predation by cats and other animals. Besides being a competitor for nesting sites, the larger Herring Gull steals eggs and hatchlings. Camouflaged eggs help prevent this, as do isolated nesting sites. While feeding, skuas, gulls, and other tern species will often harass the birds and steal their food. They often form mixed colonies with other terns, such as Common and Sandwich Terns.

Conservation status

Arctic Terns are considered threatened or species of concern in certain states. They are also among the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds applies. The species declined in New England in the late nineteenth-century due to hunting for the millinery trade. Exploitation continues today in western Greenland, where the species has declined greatly since 1950.

At the southern part of their range, the Arctic Tern has been declining in numbers. Much of this is due to shortages of food. However, most of these birds' range is extremely remote, with no apparent trend in the species as a whole.

Birdlife International has considered the species to be at lower risk since 1988, believing that there are approximately one million individuals around the world.

First evidence of the impact of climate change on Arctic Terns

by Newcastle University

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Data collected from electronic tags retrieved from 47 journeys made by the Farne Island Arctic Terns, has revealed for the first time how climate change might affect their behaviour.

Arctic Terns spend their breeding and non-breeding seasons in polar environments at opposite ends of the world and are our longest-migrating seabird.

Spending their non-breeding season in the Antarctic, the remoteness of this part of the world means that until now we have had a very limited understanding of their behaviour and distribution while they are there.

Analysing the data from 47 migrations over two study years, 2015 and 2017, the team found:

- Arctic Terns live on the Antarctic ice for one third of their annual lifecycle.

- Analysis of their feathers shows their main food source is krill or similar crustaceans.

- There were marked differences in the bird's behaviour and distribution between those tagged in 2015 compared with those tagged in 2017. This coincided with a substantial change in ice conditions, with high ice cover in 2015 followed by unusually warm conditions which led to the break-up of the ice in late 2016 and lower ice cover than normal throughout the following year.

Dr. Chris Redfern, of Newcastle University, UK, who has led the study explained:

"Sea ice is an important habitat for juvenile krill as it provides protection from predators and from the intense light of the Antarctic summer.

"We now know that krill are the main food source for the Terns so it seems likely the warmer weather during 2016/2017 led to reduced krill abundance and so the birds were forced to forage in different areas.

"And in fact, in that second year, the birds converged on the Shackleton Ice Shelf rather than being spread out along the East Antarctica coastline.

"Polar regions are particularly sensitive to climate change and even small shifts can have major implications throughout the entire food web.

"This is why it is critical to understand how seabirds such as the Arctic Terns are affected by environmental change, both short and long term."

Co-author Professor Richard Bevan, of Newcastle University, adds:

"In the course of this study, we have been continuously amazed by the incredible journeys that these seabirds make each year and now we are beginning to get a glimpse into what they are doing in their wintering areas in Antarctica.

"Arctic Terns are one of the few non-breeding birds that are present in Antarctic waters during the summer. This means the birds are not constrained to a nest site but can move to where the best feeding sites are located.

"By following the journeys made by these birds, we can monitor changes in the location of these hot spots and get some insight into environmental changes that are taking place in these very remote locations; areas to which few scientists ever venture or monitor."

The data were collected as part of a landmark study led by Newcastle University in collaboration with the National Trust, BBC Springwatch and the Natural History Society of Northumbria.

The first data retrieved from the study highlighted the incredible journey travelled by these seabirds, with one flying an estimated 96,000Km (almost 60,000 miles) from its breeding grounds on the Farne Islands, off the Northumberland coast, to its winter quarters in Antarctica.

Mapping in unprecedented detail the route and stop-off points from the Farnes to Antarctica for the winter and back again to breed, the team tracked:

- An 8,000 km, 24-day, non-stop flight over the Indian Ocean, feeding on the move

- An overland detour from the Farne Islands to the Irish Sea and over Ireland to the Atlantic

- A short stay on the New Zealand coast before completing the final leg of their journey

- A stop-off at Llangorse Lake, in the Brecon Beacons National Park, during their return journey in the Spring

"The Arctic Tern's dependence on the ice throughout their non-breeding period in Antarctica highlights the vulnerability of the species to climate change," says Dr. Redfern.

"It is well known that Arctic Terns have relatively shorter legs than other tern species and in light of what we now know, this may be an adaptation to life associated with low temperatures—the freezing point of sea water is -1.8 C and the daily average minimum temperatures recorded by the birds' data loggers was between 0 to -5 C.

"The trackers have given us a unique glimpse into the lives of these incredible birds, surviving against all the odds, and highlights how precarious their future is in the light of anthropogenic climate change."

phys.org/news/2019-11-evidence-impact-climate-arctic-terns.html

Journal Reference:

Chris P. F. Redfern et al, Use of sea ice by arctic terns Sterna paradisaea in Antarctica and impacts of climate change, Journal of Avian Biology (2019). DOI: 10.1111/jav.02318

Abstract

Arctic Terns spend their breeding and non‐breeding seasons in polar environments at opposite ends of the world. The sensitivity of polar regions to climate change makes it essential to understand the ecology of Arctic Terns but the remoteness of the Antarctic presents a considerable challenge. One solution is to use ‘biologgers’ to monitor remotely their behaviour and distribution in the Antarctic. Data from birds tagged with light‐level global location sensors (geolocators) in 2015 and 2017 showed that a third of their annual cycle was spent amongst Antarctic sea ice. After reaching the East Antarctic in the austral spring, they gradually moved west, foraging in fragmented ice zones of the Antarctic coastline, leaving in the austral autumn for their return northward migration via the Atlantic. Changes in patterns of movement between phases of 24‐h daylight and diel day/night conditions were likely linked to the annual moult, and stable isotope analyses suggest that krill (Euphausia species) was an important component of their diet. There were marked differences in movement behaviour between Arctic Terns tagged in 2015 compared to 2017 that may relate to unusual changes in sea‐ice extent. The Arctic Tern may be unique amongst seabirds that utilise the Antarctic environment in summer in being able to move widely without nesting constraints, and may present a means of characterising the effects of climate change on species dependent for foraging on Antarctic sea‐ice and krill.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jav.02318