Post by OldGreenVulture on Sept 27, 2019 11:39:33 GMT

Little Eagle - Hieraaetus morphnoides.

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Accipitriformes

Family: Accipitridae

Genus: Hieraaetus

Species: H. morphnoides

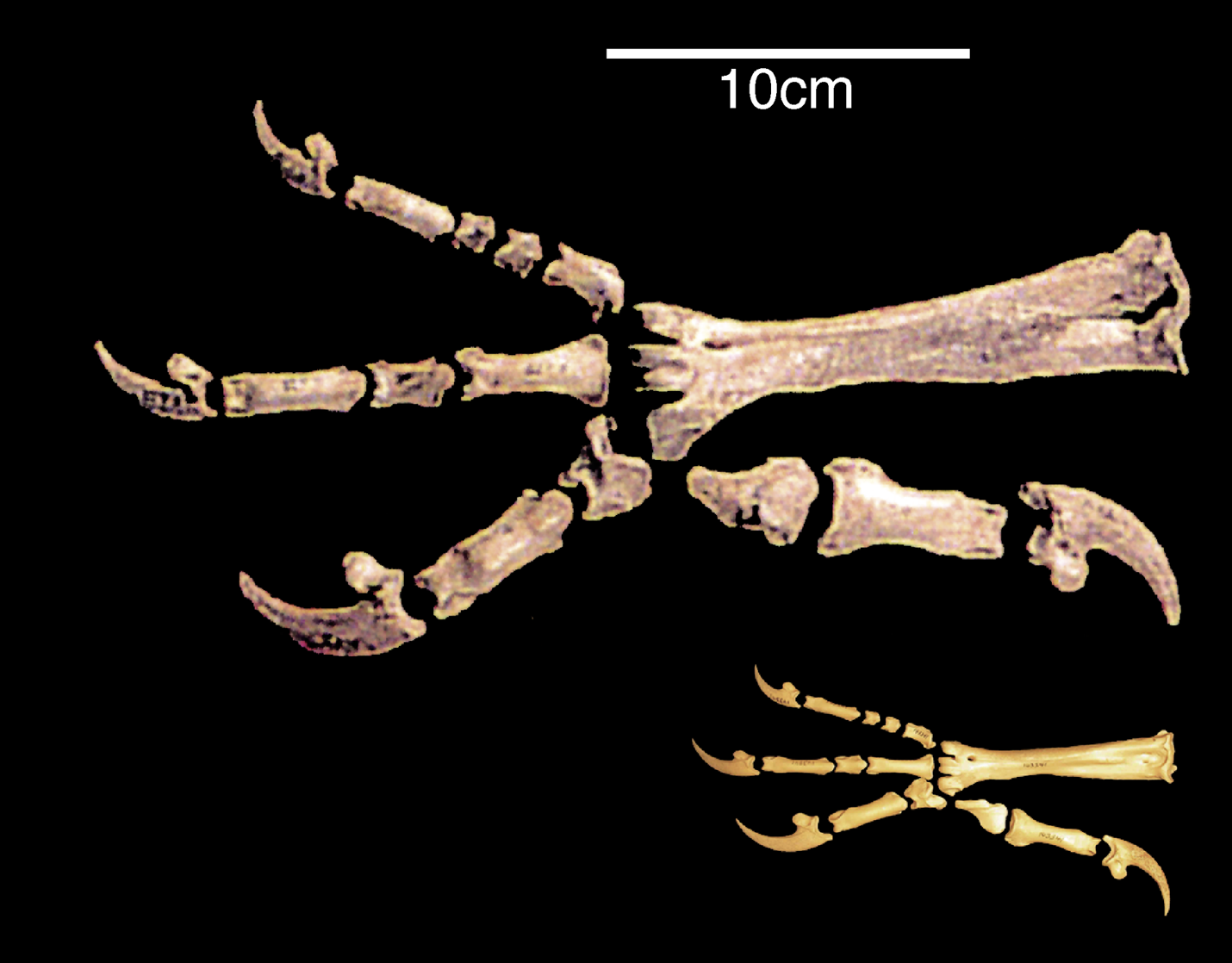

Description: Barrett, et al. (2003), describes the little eagle as a medium-sized bird of prey, between 45 and 55 cm in length. The little eagle is small and stocky with a broad head. It has fully feathered legs and a square-cut, barred tail. Wingspan is about 120 cm with males having longer wings in proportion to their bodies, but being nearly half the weight of females. It is a powerful bird and during flight has strong wing beats, glides on flat wings and soars on slightly raised or flat wings (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Olsen and Fuentes 2004; Debus 1998).

The little eagle occurs in light and dark colour forms and generally these colours change with age. The most common is the light form which is dark brown occurring on the back and wings with black streaks on the head and neck, and a sandy to pale under body. The dark form of this eagle is similar except the head and under body is usually darker brown or rich rufous. The sexes are similar with females being larger and typically darker. Juveniles are similar to adults but tend to be more strongly rufous in colour with less contrast in patterns (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Olsen and Fuentes 2004; Debus 1998).

Distribution and abundance: Although the little eagle has a large range and can be found in most parts of Australia, except heavily forested parts of the Great Dividing Range (Marchant and Higgins, 1993). Like so many Australian natives, it faces a deteriorating population due to a loss of habitat and competition from other species. One of the biggest factors to the decline of the little eagle is the decline of rabbits due to the release of the calicivirus, the eagle relied heavily on the rabbit population due to the extinction and massive decline of native terrestrial mammals of rabbit size or smaller such as large rodents, bandicoots, bettongs, juvenile banded hare-wallaby and other wallabies (Sharp et al. 2002).

In the first national bird atlas in 1977–81, the little eagle was reported in 65% of one degree grid cells across Australia, with mostly high reporting rates (more than 40% of surveys per grid) across New South Wales and Victoria. Breeding was recorded in 11% of cells, with the highest rates in New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria (Blakers et al. 1984). During the second national bird atlas in 1998–2002, the little eagle was recorded in 59% of grid cells, at mostly low reporting rates (recorded in less than 20% of surveys per grid). Breeding was recorded in 5% of grid cells (Barrett et al. 2003, 2007). Overall, there has been a national decline in reporting rate of 14%. In NSW over the last 20 years (two little eagle generations) the decline in reporting rate has been 39%, and over the past 30 years has been 50%, with an accelerating trend since the 1990s (Bounds 2008). The decline in reporting rate over the past 20 years for the South Eastern Highlands bioregion has been greater than 20% (Barrett et al. 2003, 2007). This bioregion includes the ACT.

The little eagle was once common in the ACT (Olsen and Fuentes 2004) but has undergone significant decline (greater than 70%) over the last 20 years. In the late 1980s there was an estimated 13 breeding pairs in the ACT. The species occurred mainly in the northern half of the ACT with the highest concentrations found in the Murrumbidgee and the Molonglo river corridors (Taylor and COG 1992). By 2005 the only breeding record in the ACT was of an unsuccessful nest near Uriarra Crossing (Olsen and Fuentes 2005). A more intensive ACT survey in 2007 found three breeding pairs, which fledged a total of four young (Olsen et al. 2008). In 2008 four breeding pairs were recorded and four young were fledged (Olsen et al. 2009). In 2009, three breeding pairs were recorded with three young being fledged (Olsen et al. 2010).

Typical habitat for the little eagle includes woodland or open forest. Higher abundance of the species is associated with hillsides where there is a mixture of wooded and open areas such as riparian woodlands, forest margins and wooded farmland. Little eagles usually avoid large areas of dense forest, preferring to hunt in open woodland, where the birds use trees for lookouts (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). In the ACT, little eagles inhabit frequent open woodland and riparian areas (Olsen and Fuentes 2004).

Reproduction: Little eagles nest in open woodland (usually on hillsides) and along tree-lined watercourses, with the nest typically placed in a mature, living tree. The birds build a stick nest lined with leaves and may use different nests in successive years, including those of other birds such as crows. A pair of little eagles will only reproduce once a year and each pair will only produce one or two eggs per season, usually laid in late August to early September (Marchant and Higgins 1993). After an incubation period of about 37 days, one or two young are fledged after approximately eight weeks (Olsen and Fuentes 2004; Debus et al. 2007; Debus and Ley 2009). Maturity in terms of breeding takes two to three years, leaving a large population of juvenile eagles, mature eagles constitute roughly less than three-quarters of the population (Ferguson-Lees and Christie, 2001).

Little eagle nesting territories are defended against intruders and advertised by soaring, undulating flight display, conspicuous perching and/or calling (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Debus et al. 2007; Bounds 2008). Movement behaviour varies between individuals, and may be partly migratory (being an altitudinal migrant), dispersive or permanently resident (Marchant and Higgins 1993). They tend to slip away at the first sign of human intrusion (Ferguson-lee and Christie 2001).

Prey: Little eagles hunt live prey and occasionally take carrion. The eagles search for prey by soaring, up to 500 m (1,600 ft) altitude, or by using an elevated exposed perch. The species is an agile, fast hunter swooping to take prey on the ground in the open but also from trees and shrubs (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Olsen et al. 2006; Debus et al. 2007; Debus and Ley 2009). Recorded prey species (from feeding observations, nest remains and faecal pellets) show considerable variation indicating a broad diet, which seems to be determined primarily by the availability of prey of a suitable size. The little eagle would originally feed on small birds, mammals and reptiles and supplement its diet with large insects on occasion, however with the introduction of rabbits and foxes the little eagle’s diet changed. Rabbits became widely abundant very quickly after being introduced, competing for habitat with native mammals. The introduction of foxes can also be attributed to the decline of the little eagle’s main source of prey. The rabbit however is an ideal source of prey also, and so the rabbit population became the little eagle’s main diet until the release of the calicivirus which decreased the rabbit population from between 65 and 85% in arid and semi-arid areas (Sharp et al. 2002). Debus (1998) notes that their diet varies geographically; the diet in Northern Australia has a high proportion of birds, in the arid zone is mostly lizards, and in Southern Australia has a high proportion of juvenile rabbits. In the ACT region its diet comprises mostly rabbits and to a lesser extent birds (especially rosellas, magpie-larks and starlings) (Olsen and Fuentes 2004; Olsen et al. 2006, 2010).

There is some evidence of prey partitioning between little eagles and the sympatric, larger Wedge-tailed Eagle (Aquila audax), with the latter tending to take larger prey and to eat more carrion (Baker-Gabb 1984; Debus and Rose 1999; Olsen et al. 2006, 2010). However, rabbits are the most common dietary item for both eagle species near Canberra (Olsen et al. 2010), indicating potential for competition for prey. Both species also eat carrion and it is possible that the more numerous Wedge-tailed Eagles in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) region keep little eagles away from macropod carcasses, and that little eagles would eat more carrion if not excluded by wedge-tailed eagles (Olsen et al. 2010).

Taxonomy: John Gould described the little eagle in 1841. The distinctive pygmy eagle has long been considered a subspecies, but a 2009 genetic study shows it to be distinctive genetically and warrants species status.

From Carnivora.

carnivora.net/little-eagle-hieraaetus-morphnoides-t6437.html#p61161

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Accipitriformes

Family: Accipitridae

Genus: Hieraaetus

Species: H. morphnoides

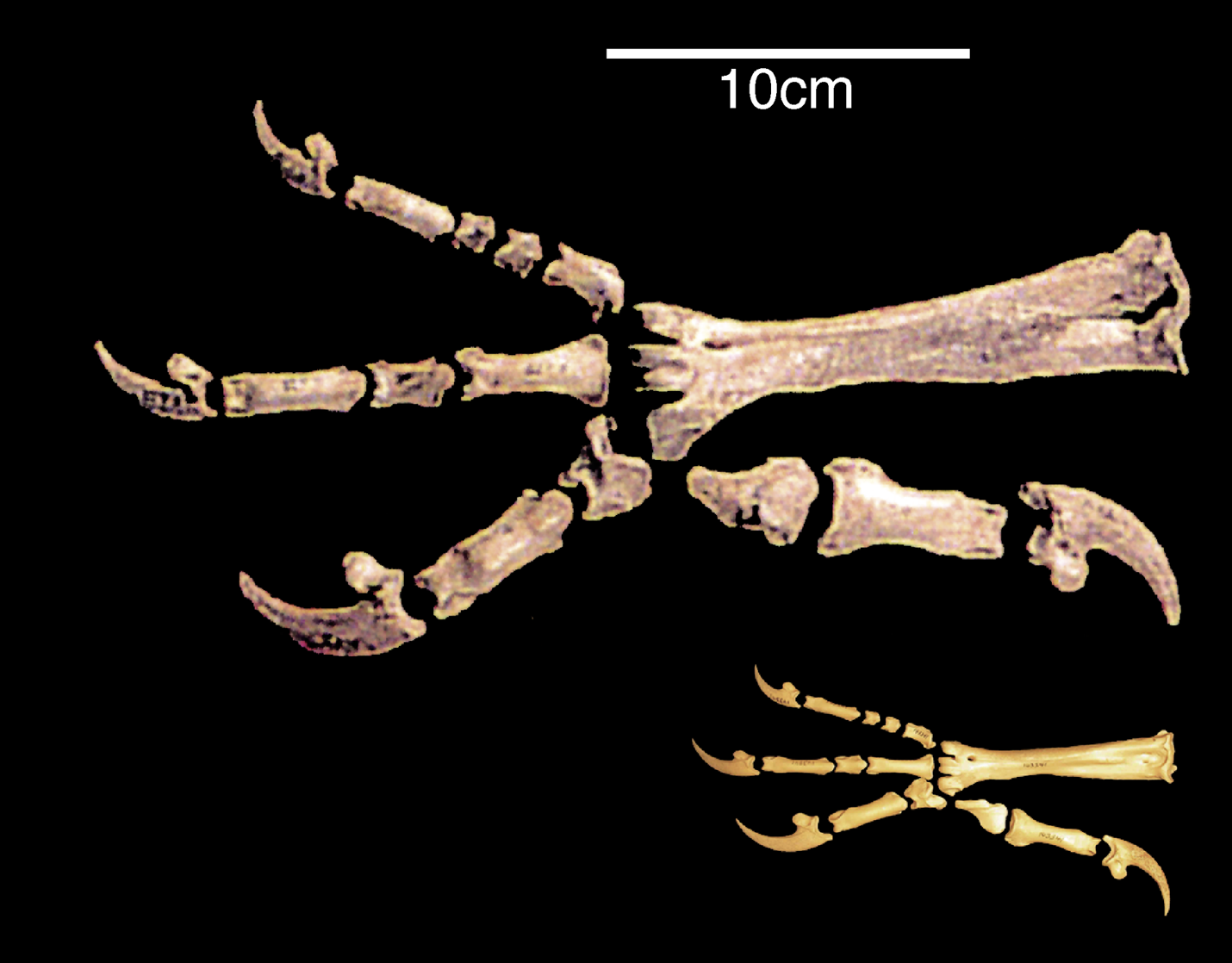

Description: Barrett, et al. (2003), describes the little eagle as a medium-sized bird of prey, between 45 and 55 cm in length. The little eagle is small and stocky with a broad head. It has fully feathered legs and a square-cut, barred tail. Wingspan is about 120 cm with males having longer wings in proportion to their bodies, but being nearly half the weight of females. It is a powerful bird and during flight has strong wing beats, glides on flat wings and soars on slightly raised or flat wings (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Olsen and Fuentes 2004; Debus 1998).

The little eagle occurs in light and dark colour forms and generally these colours change with age. The most common is the light form which is dark brown occurring on the back and wings with black streaks on the head and neck, and a sandy to pale under body. The dark form of this eagle is similar except the head and under body is usually darker brown or rich rufous. The sexes are similar with females being larger and typically darker. Juveniles are similar to adults but tend to be more strongly rufous in colour with less contrast in patterns (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Olsen and Fuentes 2004; Debus 1998).

Distribution and abundance: Although the little eagle has a large range and can be found in most parts of Australia, except heavily forested parts of the Great Dividing Range (Marchant and Higgins, 1993). Like so many Australian natives, it faces a deteriorating population due to a loss of habitat and competition from other species. One of the biggest factors to the decline of the little eagle is the decline of rabbits due to the release of the calicivirus, the eagle relied heavily on the rabbit population due to the extinction and massive decline of native terrestrial mammals of rabbit size or smaller such as large rodents, bandicoots, bettongs, juvenile banded hare-wallaby and other wallabies (Sharp et al. 2002).

In the first national bird atlas in 1977–81, the little eagle was reported in 65% of one degree grid cells across Australia, with mostly high reporting rates (more than 40% of surveys per grid) across New South Wales and Victoria. Breeding was recorded in 11% of cells, with the highest rates in New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria (Blakers et al. 1984). During the second national bird atlas in 1998–2002, the little eagle was recorded in 59% of grid cells, at mostly low reporting rates (recorded in less than 20% of surveys per grid). Breeding was recorded in 5% of grid cells (Barrett et al. 2003, 2007). Overall, there has been a national decline in reporting rate of 14%. In NSW over the last 20 years (two little eagle generations) the decline in reporting rate has been 39%, and over the past 30 years has been 50%, with an accelerating trend since the 1990s (Bounds 2008). The decline in reporting rate over the past 20 years for the South Eastern Highlands bioregion has been greater than 20% (Barrett et al. 2003, 2007). This bioregion includes the ACT.

The little eagle was once common in the ACT (Olsen and Fuentes 2004) but has undergone significant decline (greater than 70%) over the last 20 years. In the late 1980s there was an estimated 13 breeding pairs in the ACT. The species occurred mainly in the northern half of the ACT with the highest concentrations found in the Murrumbidgee and the Molonglo river corridors (Taylor and COG 1992). By 2005 the only breeding record in the ACT was of an unsuccessful nest near Uriarra Crossing (Olsen and Fuentes 2005). A more intensive ACT survey in 2007 found three breeding pairs, which fledged a total of four young (Olsen et al. 2008). In 2008 four breeding pairs were recorded and four young were fledged (Olsen et al. 2009). In 2009, three breeding pairs were recorded with three young being fledged (Olsen et al. 2010).

Typical habitat for the little eagle includes woodland or open forest. Higher abundance of the species is associated with hillsides where there is a mixture of wooded and open areas such as riparian woodlands, forest margins and wooded farmland. Little eagles usually avoid large areas of dense forest, preferring to hunt in open woodland, where the birds use trees for lookouts (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). In the ACT, little eagles inhabit frequent open woodland and riparian areas (Olsen and Fuentes 2004).

Reproduction: Little eagles nest in open woodland (usually on hillsides) and along tree-lined watercourses, with the nest typically placed in a mature, living tree. The birds build a stick nest lined with leaves and may use different nests in successive years, including those of other birds such as crows. A pair of little eagles will only reproduce once a year and each pair will only produce one or two eggs per season, usually laid in late August to early September (Marchant and Higgins 1993). After an incubation period of about 37 days, one or two young are fledged after approximately eight weeks (Olsen and Fuentes 2004; Debus et al. 2007; Debus and Ley 2009). Maturity in terms of breeding takes two to three years, leaving a large population of juvenile eagles, mature eagles constitute roughly less than three-quarters of the population (Ferguson-Lees and Christie, 2001).

Little eagle nesting territories are defended against intruders and advertised by soaring, undulating flight display, conspicuous perching and/or calling (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Debus et al. 2007; Bounds 2008). Movement behaviour varies between individuals, and may be partly migratory (being an altitudinal migrant), dispersive or permanently resident (Marchant and Higgins 1993). They tend to slip away at the first sign of human intrusion (Ferguson-lee and Christie 2001).

Prey: Little eagles hunt live prey and occasionally take carrion. The eagles search for prey by soaring, up to 500 m (1,600 ft) altitude, or by using an elevated exposed perch. The species is an agile, fast hunter swooping to take prey on the ground in the open but also from trees and shrubs (Marchant and Higgins 1993; Olsen et al. 2006; Debus et al. 2007; Debus and Ley 2009). Recorded prey species (from feeding observations, nest remains and faecal pellets) show considerable variation indicating a broad diet, which seems to be determined primarily by the availability of prey of a suitable size. The little eagle would originally feed on small birds, mammals and reptiles and supplement its diet with large insects on occasion, however with the introduction of rabbits and foxes the little eagle’s diet changed. Rabbits became widely abundant very quickly after being introduced, competing for habitat with native mammals. The introduction of foxes can also be attributed to the decline of the little eagle’s main source of prey. The rabbit however is an ideal source of prey also, and so the rabbit population became the little eagle’s main diet until the release of the calicivirus which decreased the rabbit population from between 65 and 85% in arid and semi-arid areas (Sharp et al. 2002). Debus (1998) notes that their diet varies geographically; the diet in Northern Australia has a high proportion of birds, in the arid zone is mostly lizards, and in Southern Australia has a high proportion of juvenile rabbits. In the ACT region its diet comprises mostly rabbits and to a lesser extent birds (especially rosellas, magpie-larks and starlings) (Olsen and Fuentes 2004; Olsen et al. 2006, 2010).

There is some evidence of prey partitioning between little eagles and the sympatric, larger Wedge-tailed Eagle (Aquila audax), with the latter tending to take larger prey and to eat more carrion (Baker-Gabb 1984; Debus and Rose 1999; Olsen et al. 2006, 2010). However, rabbits are the most common dietary item for both eagle species near Canberra (Olsen et al. 2010), indicating potential for competition for prey. Both species also eat carrion and it is possible that the more numerous Wedge-tailed Eagles in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) region keep little eagles away from macropod carcasses, and that little eagles would eat more carrion if not excluded by wedge-tailed eagles (Olsen et al. 2010).

Taxonomy: John Gould described the little eagle in 1841. The distinctive pygmy eagle has long been considered a subspecies, but a 2009 genetic study shows it to be distinctive genetically and warrants species status.

From Carnivora.

carnivora.net/little-eagle-hieraaetus-morphnoides-t6437.html#p61161