Post by Eaglehawk on Sept 24, 2019 7:59:18 GMT

European Shag - Phalacrocorax aristotelis

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Suliformes

Family: Phalacrocoracidae

Genus: Phalacrocorax

Species: Phalacrocorax aristotelis

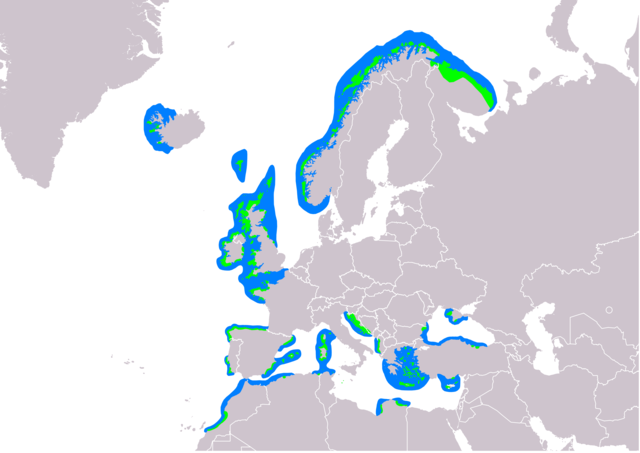

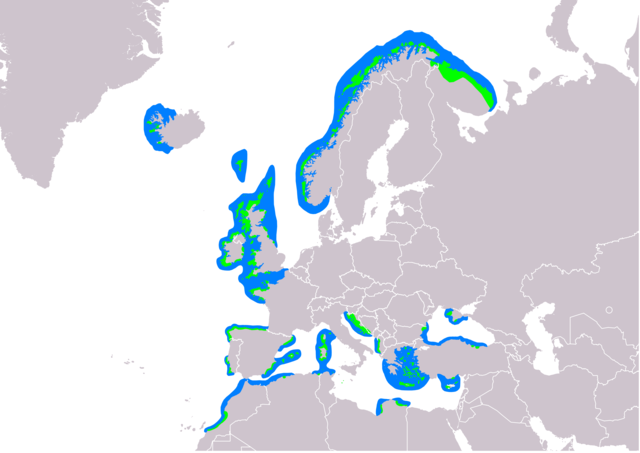

The European shag or common shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) is a species of cormorant. It breeds around the rocky coasts of western and southern Europe, southwest Asia and north Africa, mainly wintering in its breeding range except for the northernmost birds. In Britain this seabird is usually referred to as simply the shag.

Description

This is a medium-large black bird, 68 to 78 cm (27 to 31 in) long and with a 95-to-110-centimetre (37 to 43 in) wingspan. It has a longish tail and yellow throat-patch. Adults have a small crest in the breeding season. It is distinguished from the great cormorant by its smaller size, lighter build, thinner bill, and, in breeding adults, by the crest and metallic green-tinged sheen on the feathers. Among those differences are that a shag has a lighter, narrower beak; and the juvenile shag has darker underparts. The European shag's tail has 12 feathers, the great cormorant's 14 feathers. The green sheen on the feathers results in the alternative name green cormorant sometimes being given to the European shag.

Habitat

It feeds in the sea, and, unlike the great cormorant, is rare inland. It will winter along any coast that is well-supplied with fish.

The European shag is one of the deepest divers among the cormorant family. Using depth gauges, European shags have been shown to dive to at least 45 m (148 ft). European shags are preponderantly benthic feeders, i.e. they find their prey on the sea bottom. They will eat a wide range of fish but their commonest prey is the sand eel. Shags will travel many kilometres from their roosting sites in order to feed.

In UK coastal waters, dive times are typically around 20 to 45 seconds, with a recovery time of around 15 seconds between dives; this is consistent with aerobic diving, i.e. the bird depends on the oxygen in its lungs and dissolved in its bloodstream during the dive. When they dive, they jump out of the water first to give extra impetus to the dive.

It breeds on coasts, nesting on rocky ledges or in crevices or small caves. The nests are untidy heaps of rotting seaweed or twigs cemented together by the bird's own guano. The nesting season is long, beginning in late February but some nests not started until May or even later. Three eggs are laid. Their chicks hatch without down and so they rely totally on their parents for warmth, often for a period of two months before they can fly. Fledging may occur at any time from early June to late August, exceptionally to mid-October.

Subspecies

There are three subspecies:

The subspecies differ slightly in bill size and the breast and leg colour of young birds. Recent evidence suggests that birds on the Atlantic coast of southwest Europe are distinct from all three, and may be an as-yet undescribed subspecies.

The name shag is also used in the Southern Hemisphere for several additional species of cormorants.

Example locations

The European shag can be readily be seen at the following breeding locations in the season (late April to mid July): Farne Islands, England; Deerness and Fowlsheugh, Scotland; Runde, Norway; Iceland, Faroe Islands and Galicia.

The largest colony of European shags is in the Cíes Islands, with 2,500 pairs (25% of the world's population).

Worsening wind forecasts signal stormy times ahead for seabirds

Date: August 18, 2015

Source: University of Edinburgh

Stronger winds forecast as a result of climate change could impact on populations of wild animals, by affecting how well they can feed, a study of seabirds suggests.

Research into a common UK coastal seabird showed that when winds are strong, females take much longer to find food compared with their male counterparts.

Researchers expect that if wind conditions worsen -- as they are forecast to do -- this could impact on the wellbeing of female birds, and ultimately affect population sizes.

In many seabird species, females are smaller and lighter than males, and so must work harder to dive through turbulent water. They may not hold their breath for as long, fly so efficiently nor dive as deeply as males. The latest results suggest that in poor weather conditions, this sex difference is exaggerated.

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh, the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (CEH) and British Antarctic Survey carried out their two-year study into cormorant-like birds, known as shags, on the Isle of May National Nature Reserve in south-east Scotland. Small tracking devices were attached to the legs of birds and measured how long they foraged for fish in the sea.

Scientists found that when coastal winds were strong or blowing towards the shore, females took much longer to find food compared with males. The difference in time spent foraging became more marked between the sexes when conditions worsened, suggesting that female birds are more likely to continue foraging even in the poorest conditions.

Scientists say their findings may apply to many other species in which there are sex differences in foraging. Their research, carried out as part of a long-term CEH study on the island that began in the 1970s, was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and published in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

Dr Sue Lewis, of the University of Edinburgh's School of Biological Sciences, who led the study, said: "In our study, females had to work harder than males to find food, and difficult conditions exacerbated this difference. Forecasted increases in wind speeds could have a greater impact on females, with potential knock-on effects on the well-being of populations."

Dr Francis Daunt, of the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, said "Most of the research on climate change has focussed on the effects of warming, but there is growing concern about increasing wind speeds and frequency of storms. This study shows one way in which wind could affect wild populations, and may be widespread since many species have sex differences in body size."

Story Source: University of Edinburgh. "Worsening wind forecasts signal stormy times ahead for seabirds." ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/08/150818112421.htm (accessed August 19, 2015).

Journal Reference:

Sue Lewis, Richard A. Phillips, Sarah J. Burthe, Sarah Wanless, Francis Daunt. Contrasting responses of male and female foraging effort to year-round wind conditions.Journal of Animal Ecology, 2015; DOI: 10.1111/1365-2656.12419

Summary

1. There is growing interest in the effects of wind on wild animals, given evidence that wind speeds are increasing and becoming more variable in some regions, particularly at temperate latitudes. Wind may alter movement patterns or foraging ability, with consequences for energy budgets and, ultimately, demographic rates.

2. These effects are expected to vary among individuals due to intrinsic factors such as sex, age or feeding proficiency. Furthermore, this variation is predicted to become more marked as wind conditions deteriorate, which may have profound consequences for population dynamics as the climate changes. However, the interaction between wind and intrinsic effects has not been comprehensively tested.

3. In many species, in particular those showing sexual size dimorphism, males and females vary in foraging performance. Here, we undertook year-round deployments of data loggers to test for interactions between sex and wind speed and direction on foraging effort in adult European shags Phalacrocorax aristotelis, a pursuit-diving seabird in which males are c. 18% heavier.

4. We found that foraging time was lower at high wind speeds but higher during easterly (onshore) winds. Furthermore, there was an interaction between sex and wind conditions on foraging effort, such that females foraged for longer than males when winds were of greater strength (9% difference at high wind speeds vs. 1% at low wind speeds) and when winds were easterly compared with westerly (7% and 4% difference, respectively).

5. The results supported our prediction that sex-specific differences in foraging effort would become more marked as wind conditions worsen. Since foraging time is linked to demographic rates in this species, our findings are likely to have important consequences for population dynamics by amplifying sex-specific differences in survival rates.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2656.12419/abstract;jsessionid=29CB5E69D4423C8DD521B9F0AB84A259.f03t04

Diving birds follow each other when fishing

by University of Exeter

European shags. Credit: Julian Evans

Diving seabirds watch each other to work out when to dive, new research shows.

Scientists studied European shags and found they were twice as likely to dive after seeing a fellow bird go underwater.

The study is the first to investigate why large groups (known as "rafts") of shags dive together at sea.

University of Exeter scientists filmed the birds off the Isles of Scilly to examine their behaviour.

"Our results suggest these birds aren't just reacting to underwater cues when deciding where and when to dive," said Dr. Julian Evans, who led the study as part of his Ph.D. at the University of Exeter.

"They respond to social cues by watching their fellow birds and copying their behaviour.

"They're essentially using other flock members as sources of information, helping them choose the best place to find fish."

This behaviour might bring various benefits, and more research is needed to fully understand it.

"Watching other birds could help shags save energy by reducing the need for uninformed sample dives," said Dr. Evans.

"Diving in the same area as another bird might also be beneficial because the prey might be disorganised, pushed into certain areas or fatigued by previous divers."

Dr. Evans said it was important to understand the behaviour of European shags because they—like most seabird species—are under "great pressure" due to declining fish stocks, climate change and habitat loss.

European shags Credit: Julian Evans

The paper, published in the journal PLOS One, is entitled: "Social information use and collective foraging in a pursuit diving seabird."

phys.org/news/2019-09-birds-fishing.html

Journal Reference:

Evans JC, Torney CJ, Votier SC, Dall SRX (2019) Social information use and collective foraging in a pursuit diving seabird. PLoS ONE 14(9): e0222600. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222600

Abstract

Individuals of many species utilise social information whilst making decisions. While many studies have examined social information in making large scale decisions, there is increasing interest in the use of fine scale social cues in groups. By examining the use of these cues and how they alter behaviour, we can gain insights into the adaptive value of group behaviours. We investigated the role of social information in choosing when and where to dive in groups of socially foraging European shags. From this we aimed to determine the importance of social information in the formation of these groups. We extracted individuals’ surface trajectories and dive locations from video footage of collective foraging and used computational Bayesian methods to infer how social interactions influence diving. Examination of group spatial structure shows birds form structured aggregations with higher densities of conspecifics directly in front of and behind focal individuals. Analysis of diving behaviour reveals two distinct rates of diving, with birds over twice as likely to dive if a conspecific dived within their visual field in the immediate past. These results suggest that shag group foraging behaviour allows individuals to sense and respond to their environment more effectively by making use of social cues.

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0222600

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Suliformes

Family: Phalacrocoracidae

Genus: Phalacrocorax

Species: Phalacrocorax aristotelis

The European shag or common shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) is a species of cormorant. It breeds around the rocky coasts of western and southern Europe, southwest Asia and north Africa, mainly wintering in its breeding range except for the northernmost birds. In Britain this seabird is usually referred to as simply the shag.

Description

This is a medium-large black bird, 68 to 78 cm (27 to 31 in) long and with a 95-to-110-centimetre (37 to 43 in) wingspan. It has a longish tail and yellow throat-patch. Adults have a small crest in the breeding season. It is distinguished from the great cormorant by its smaller size, lighter build, thinner bill, and, in breeding adults, by the crest and metallic green-tinged sheen on the feathers. Among those differences are that a shag has a lighter, narrower beak; and the juvenile shag has darker underparts. The European shag's tail has 12 feathers, the great cormorant's 14 feathers. The green sheen on the feathers results in the alternative name green cormorant sometimes being given to the European shag.

Habitat

It feeds in the sea, and, unlike the great cormorant, is rare inland. It will winter along any coast that is well-supplied with fish.

The European shag is one of the deepest divers among the cormorant family. Using depth gauges, European shags have been shown to dive to at least 45 m (148 ft). European shags are preponderantly benthic feeders, i.e. they find their prey on the sea bottom. They will eat a wide range of fish but their commonest prey is the sand eel. Shags will travel many kilometres from their roosting sites in order to feed.

In UK coastal waters, dive times are typically around 20 to 45 seconds, with a recovery time of around 15 seconds between dives; this is consistent with aerobic diving, i.e. the bird depends on the oxygen in its lungs and dissolved in its bloodstream during the dive. When they dive, they jump out of the water first to give extra impetus to the dive.

It breeds on coasts, nesting on rocky ledges or in crevices or small caves. The nests are untidy heaps of rotting seaweed or twigs cemented together by the bird's own guano. The nesting season is long, beginning in late February but some nests not started until May or even later. Three eggs are laid. Their chicks hatch without down and so they rely totally on their parents for warmth, often for a period of two months before they can fly. Fledging may occur at any time from early June to late August, exceptionally to mid-October.

Subspecies

There are three subspecies:

- P. a. aristotelis – (Linnaeus, 1761): nominate, found in northwestern Europe (Atlantic Ocean coasts)

- P. a. desmarestii – (Payraudeau, 1826): found in southern Europe, southwest Asia (Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts)

- P. a. riggenbachi – Hartert, 1923: found in northwest African coast

The subspecies differ slightly in bill size and the breast and leg colour of young birds. Recent evidence suggests that birds on the Atlantic coast of southwest Europe are distinct from all three, and may be an as-yet undescribed subspecies.

The name shag is also used in the Southern Hemisphere for several additional species of cormorants.

Example locations

The European shag can be readily be seen at the following breeding locations in the season (late April to mid July): Farne Islands, England; Deerness and Fowlsheugh, Scotland; Runde, Norway; Iceland, Faroe Islands and Galicia.

The largest colony of European shags is in the Cíes Islands, with 2,500 pairs (25% of the world's population).

Worsening wind forecasts signal stormy times ahead for seabirds

Date: August 18, 2015

Source: University of Edinburgh

Stronger winds forecast as a result of climate change could impact on populations of wild animals, by affecting how well they can feed, a study of seabirds suggests.

Research into a common UK coastal seabird showed that when winds are strong, females take much longer to find food compared with their male counterparts.

Researchers expect that if wind conditions worsen -- as they are forecast to do -- this could impact on the wellbeing of female birds, and ultimately affect population sizes.

In many seabird species, females are smaller and lighter than males, and so must work harder to dive through turbulent water. They may not hold their breath for as long, fly so efficiently nor dive as deeply as males. The latest results suggest that in poor weather conditions, this sex difference is exaggerated.

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh, the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (CEH) and British Antarctic Survey carried out their two-year study into cormorant-like birds, known as shags, on the Isle of May National Nature Reserve in south-east Scotland. Small tracking devices were attached to the legs of birds and measured how long they foraged for fish in the sea.

Scientists found that when coastal winds were strong or blowing towards the shore, females took much longer to find food compared with males. The difference in time spent foraging became more marked between the sexes when conditions worsened, suggesting that female birds are more likely to continue foraging even in the poorest conditions.

Scientists say their findings may apply to many other species in which there are sex differences in foraging. Their research, carried out as part of a long-term CEH study on the island that began in the 1970s, was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and published in the Journal of Animal Ecology.

Dr Sue Lewis, of the University of Edinburgh's School of Biological Sciences, who led the study, said: "In our study, females had to work harder than males to find food, and difficult conditions exacerbated this difference. Forecasted increases in wind speeds could have a greater impact on females, with potential knock-on effects on the well-being of populations."

Dr Francis Daunt, of the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, said "Most of the research on climate change has focussed on the effects of warming, but there is growing concern about increasing wind speeds and frequency of storms. This study shows one way in which wind could affect wild populations, and may be widespread since many species have sex differences in body size."

Story Source: University of Edinburgh. "Worsening wind forecasts signal stormy times ahead for seabirds." ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/08/150818112421.htm (accessed August 19, 2015).

Journal Reference:

Sue Lewis, Richard A. Phillips, Sarah J. Burthe, Sarah Wanless, Francis Daunt. Contrasting responses of male and female foraging effort to year-round wind conditions.Journal of Animal Ecology, 2015; DOI: 10.1111/1365-2656.12419

Summary

1. There is growing interest in the effects of wind on wild animals, given evidence that wind speeds are increasing and becoming more variable in some regions, particularly at temperate latitudes. Wind may alter movement patterns or foraging ability, with consequences for energy budgets and, ultimately, demographic rates.

2. These effects are expected to vary among individuals due to intrinsic factors such as sex, age or feeding proficiency. Furthermore, this variation is predicted to become more marked as wind conditions deteriorate, which may have profound consequences for population dynamics as the climate changes. However, the interaction between wind and intrinsic effects has not been comprehensively tested.

3. In many species, in particular those showing sexual size dimorphism, males and females vary in foraging performance. Here, we undertook year-round deployments of data loggers to test for interactions between sex and wind speed and direction on foraging effort in adult European shags Phalacrocorax aristotelis, a pursuit-diving seabird in which males are c. 18% heavier.

4. We found that foraging time was lower at high wind speeds but higher during easterly (onshore) winds. Furthermore, there was an interaction between sex and wind conditions on foraging effort, such that females foraged for longer than males when winds were of greater strength (9% difference at high wind speeds vs. 1% at low wind speeds) and when winds were easterly compared with westerly (7% and 4% difference, respectively).

5. The results supported our prediction that sex-specific differences in foraging effort would become more marked as wind conditions worsen. Since foraging time is linked to demographic rates in this species, our findings are likely to have important consequences for population dynamics by amplifying sex-specific differences in survival rates.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2656.12419/abstract;jsessionid=29CB5E69D4423C8DD521B9F0AB84A259.f03t04

Diving birds follow each other when fishing

by University of Exeter

European shags. Credit: Julian Evans

Diving seabirds watch each other to work out when to dive, new research shows.

Scientists studied European shags and found they were twice as likely to dive after seeing a fellow bird go underwater.

The study is the first to investigate why large groups (known as "rafts") of shags dive together at sea.

University of Exeter scientists filmed the birds off the Isles of Scilly to examine their behaviour.

"Our results suggest these birds aren't just reacting to underwater cues when deciding where and when to dive," said Dr. Julian Evans, who led the study as part of his Ph.D. at the University of Exeter.

"They respond to social cues by watching their fellow birds and copying their behaviour.

"They're essentially using other flock members as sources of information, helping them choose the best place to find fish."

This behaviour might bring various benefits, and more research is needed to fully understand it.

"Watching other birds could help shags save energy by reducing the need for uninformed sample dives," said Dr. Evans.

"Diving in the same area as another bird might also be beneficial because the prey might be disorganised, pushed into certain areas or fatigued by previous divers."

Dr. Evans said it was important to understand the behaviour of European shags because they—like most seabird species—are under "great pressure" due to declining fish stocks, climate change and habitat loss.

European shags Credit: Julian Evans

The paper, published in the journal PLOS One, is entitled: "Social information use and collective foraging in a pursuit diving seabird."

phys.org/news/2019-09-birds-fishing.html

Journal Reference:

Evans JC, Torney CJ, Votier SC, Dall SRX (2019) Social information use and collective foraging in a pursuit diving seabird. PLoS ONE 14(9): e0222600. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222600

Abstract

Individuals of many species utilise social information whilst making decisions. While many studies have examined social information in making large scale decisions, there is increasing interest in the use of fine scale social cues in groups. By examining the use of these cues and how they alter behaviour, we can gain insights into the adaptive value of group behaviours. We investigated the role of social information in choosing when and where to dive in groups of socially foraging European shags. From this we aimed to determine the importance of social information in the formation of these groups. We extracted individuals’ surface trajectories and dive locations from video footage of collective foraging and used computational Bayesian methods to infer how social interactions influence diving. Examination of group spatial structure shows birds form structured aggregations with higher densities of conspecifics directly in front of and behind focal individuals. Analysis of diving behaviour reveals two distinct rates of diving, with birds over twice as likely to dive if a conspecific dived within their visual field in the immediate past. These results suggest that shag group foraging behaviour allows individuals to sense and respond to their environment more effectively by making use of social cues.

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0222600