Post by Eaglehawk on Sept 18, 2019 8:30:28 GMT

Little Bustard - Tetrax tetrax

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Otidiformes

Family: Otididae

Genus: Tetrax T. Forster, 1817

Species: Tetrax tetrax (Linnaeus, 1758)

The little bustard (Tetrax tetrax) is a large bird in the bustard family, the only member of the genus Tetrax. The genus name is from Ancient Greek and refers to a gamebird mentioned by Aristophanes and others.

It breeds in southern Europe and in western and central Asia. Southernmost European birds are mainly resident, but other populations migrate further south in winter. The central European population once breeding in the grassland of Hungary became extinct several decades ago.

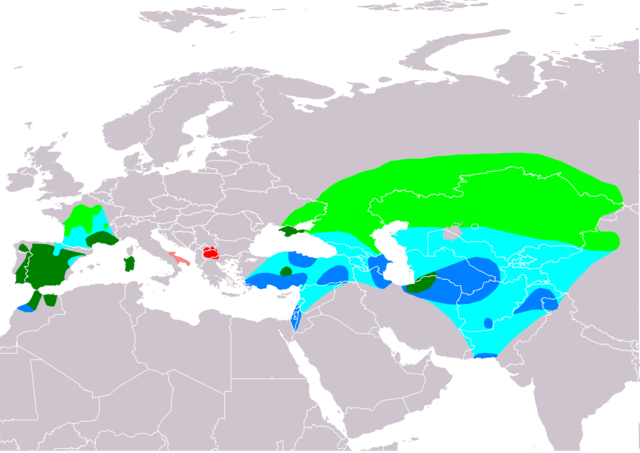

Range of T. tetrax Breeding Resident Non-breeding Passage Probably extinct Extinct

This species is declining due to habitat loss throughout its range. It used to breed more widely, for example ranging north to Poland occasionally. It is only a very rare vagrant to Great Britain despite breeding in France.

Although the smallest Palearctic bustard, the little bustard is still pheasant-sized at 42–45 cm (17–18 in) long with a 90–110 cm (35–43 in) wingspan and a weight of 830 g (29 oz). In flight, the long wings are extensively white. The breeding male is brown above and white below, with a grey head and a black neck bordered above and below by white.

The female and non-breeding male lack the dramatic neck pattern, and the female is marked darker below than the male. Immature bustards resemble females. Both sexes are usually silent, although the male has a distinctive "raspberry-blowing" call: prrt.

This species is omnivorous, taking seeds, insects, rodents and reptiles. Like other bustards, the male little bustard has a flamboyant display with foot stamping and leaping in the air. Females lay 3 to 5 eggs on the ground.

This bird's habitat is open grassland and undisturbed cultivation, with plants tall enough for cover. Males and females do not differ markedly in habitat selection. It has a stately slow walk, and tends to run when disturbed rather than fly. It is gregarious, especially in winter.

On 20 December 2013, the Cypriot newspapers 'Fileleftheros' and 'Politis', as well as news website 'SigmaLive', reported the discovery of a dead little bustard in the United Nations Buffer Zone. The bird had been shot by poachers hunting illegally in the zone. The shooting was particularly controversial amongst conservationists and birders since the little bustard is a very rare visitor to Cyprus and had not been officially recorded in Cyprus since December 1979.

Global warming makes it harder for birds to mate, study finds

by University of East Anglia

Credit: University of East Anglia

New research led by the University of East Anglia (UEA) and University of Porto (CIBIO-InBIO) shows how global warming could reduce the mating activity and success of grassland birds.

The study examined the threatened grassland bird Tetrax tetrax, or little bustard, classified as a vulnerable species in Europe, in order to test how rising temperatures could affect future behavior.

The males spend most of their time in April and May trying to attract females in a breeding gathering known as a lek. In leks, to get noticed, males stand upright, puff up their necks, and making a call that sounds like a 'snort." They also use this display to defend their territory from competing breeding males.

The international team of researchers—from the UK, Kenya, Portugal, Spain and Brazil—found that high temperatures reduced this snort-call display behavior. If temperatures become too hot, birds may have to choose between mating and sheltering or resting to save their energy and protect themselves from the heat.

Published in the journal PLOS ONE, the findings show that during the mating season little bustard display behavior is significantly related to temperature, the time of the day—something referred to as circadian rhythms—and what stage of the mating season it is. The average temperature during the day also affects how much birds display and again as temperatures increase, display rates reduce.

In the study region of the Iberian Peninsula, average daily daytime (5:00—21:00 hours) temperatures varied between 10ºC and 31ºC. Snort-call display probability decreased substantially as temperature increased from 4 to 20ºC, stabilized from 20 to 30ºC, and decreased thereafter.

The researchers warn that the average display activity of the birds will continue to reduce by up to 10 percent for the temperature increases projected by 2100 in this region due to global warming.

Mishal Gudka, who led the research while at UEA's School of Biological Sciences, said: "This work has shown how global warming may affect important behavioral mechanisms using the mating system of a lekking grassland bird species as an example.

"For lekking birds and mammals undertaking these types of extravagant and energetic displays in a warming climate, less display activity could affect how females choose mates, providing an opportunity for genetically weaker males to mate more frequently. This in turn could lead to more failed copulation attempts, lower fertilization success and weaker offspring, reducing the overall population health.

"Unfortunately for little bustards, these potential consequences of reduced display combined with other existing threats such as loss of habitat, may push this endangered species towards local and regional extinctions."

The team used a novel method to understand how display behavior of little bustards is affected by temperature changes. Remote GPS/GSM accelerometer tracking devices were fitted to 17 wild male little bustards living at five sites in Spain and Portugal.

The researchers filmed the birds to observe their behavior at the same time as accelerometers recorded their position, and using this information they were able to determine the acceleration signature or pattern for snort-calling behavior.

Co-author Paul Dolman, Professor of Conservation Ecology at UEA's School of Environmental Sciences, said: "Many people are familiar with the impacts of global warming on wildlife through droughts, storms or wildfires as well as earlier migration with warming springs. But climate change affects species in many other subtle ways that may cause unexpected changes.

"Little bustards living in the Iberian Peninsula are already exposed to some of the highest temperatures within their species range. They are one of many bird and mammal species that have an extravagant, energetically demanding display ritual, meaning they are all susceptible to the same issue.

"Our findings highlight the need for further work to understand the mechanisms that underlie responses to climate change and to assess implications these changes may have at a population level."

The authors say the study is a replicable example of how tracking technology and acceleration data can be used to answer research questions with important conservation implications related to the impacts of climate change on a range of different animals.

The technology used in this work—GPS/GSM accelerometers—was developed by Movetech Telemetry, a scientific partnership involving UEA, the British Trust for Ornithology, CIBIO/InBIO at the University of Porto, and the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Lisbon, working together to develop animal tracking solutions.

phys.org/news/2019-09-global-harder-birds.html

Journal Reference:

Mishal Gudka et al. Feeling the heat: Elevated temperature affects male display activity of a lekking grassland bird, PLOS ONE (2019). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221999

Abstract

Most species-climate models relate range margins to long-term mean climate but lack mechanistic understanding of the ecological or demographic processes underlying the climate response. We examined the case of a climatically limited edge-of-range population of a medium-sized grassland bird, for which climate responses may involve a behavioural trade-off between temperature stress and reproduction. We hypothesised that temperature will be a limiting factor for the conspicuous, male snort-call display behaviour, and high temperatures would reduce the display activity of male birds. Using remote tracking technology with tri-axial accelerometers we classified and studied the display behaviour of 17 free-ranging male little bustards, Tetrax tetrax, at 5 sites in the Iberian Peninsula. Display behaviour was related to temperature using two classes of Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs) at different temporal resolutions. GAMMs showed that temperature, time of the day and Julian date explained variation in display behaviour within the day, with birds snort-calling significantly less during higher temperatures. We also showed that variation in daily snort-call activity was related to average daytime temperatures, with our model predicting an average decrease in daytime snort-call display activity of up to 10.4% for the temperature increases projected by 2100 in this region due to global warming. For lekking birds and mammals undertaking energetically-costly displays in a warming climate, reduced display behaviour could impact inter- and intra-sex mating behaviour interactions through sexual selection and mate choice mechanisms, with possible consequences on mating and reproductive success. The study provides a reproducible example for how accelerometer data can be used to answer research questions with important conservation inferences related to the impacts of climate change on a range of taxonomic groups.

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0221999

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Otidiformes

Family: Otididae

Genus: Tetrax T. Forster, 1817

Species: Tetrax tetrax (Linnaeus, 1758)

The little bustard (Tetrax tetrax) is a large bird in the bustard family, the only member of the genus Tetrax. The genus name is from Ancient Greek and refers to a gamebird mentioned by Aristophanes and others.

It breeds in southern Europe and in western and central Asia. Southernmost European birds are mainly resident, but other populations migrate further south in winter. The central European population once breeding in the grassland of Hungary became extinct several decades ago.

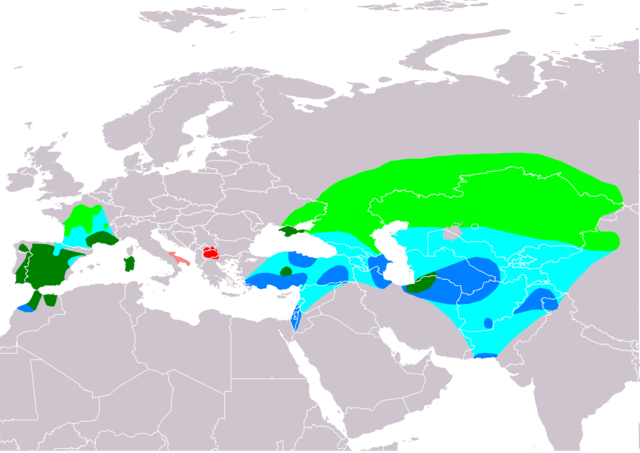

Range of T. tetrax Breeding Resident Non-breeding Passage Probably extinct Extinct

This species is declining due to habitat loss throughout its range. It used to breed more widely, for example ranging north to Poland occasionally. It is only a very rare vagrant to Great Britain despite breeding in France.

Although the smallest Palearctic bustard, the little bustard is still pheasant-sized at 42–45 cm (17–18 in) long with a 90–110 cm (35–43 in) wingspan and a weight of 830 g (29 oz). In flight, the long wings are extensively white. The breeding male is brown above and white below, with a grey head and a black neck bordered above and below by white.

The female and non-breeding male lack the dramatic neck pattern, and the female is marked darker below than the male. Immature bustards resemble females. Both sexes are usually silent, although the male has a distinctive "raspberry-blowing" call: prrt.

This species is omnivorous, taking seeds, insects, rodents and reptiles. Like other bustards, the male little bustard has a flamboyant display with foot stamping and leaping in the air. Females lay 3 to 5 eggs on the ground.

This bird's habitat is open grassland and undisturbed cultivation, with plants tall enough for cover. Males and females do not differ markedly in habitat selection. It has a stately slow walk, and tends to run when disturbed rather than fly. It is gregarious, especially in winter.

On 20 December 2013, the Cypriot newspapers 'Fileleftheros' and 'Politis', as well as news website 'SigmaLive', reported the discovery of a dead little bustard in the United Nations Buffer Zone. The bird had been shot by poachers hunting illegally in the zone. The shooting was particularly controversial amongst conservationists and birders since the little bustard is a very rare visitor to Cyprus and had not been officially recorded in Cyprus since December 1979.

Global warming makes it harder for birds to mate, study finds

by University of East Anglia

Credit: University of East Anglia

New research led by the University of East Anglia (UEA) and University of Porto (CIBIO-InBIO) shows how global warming could reduce the mating activity and success of grassland birds.

The study examined the threatened grassland bird Tetrax tetrax, or little bustard, classified as a vulnerable species in Europe, in order to test how rising temperatures could affect future behavior.

The males spend most of their time in April and May trying to attract females in a breeding gathering known as a lek. In leks, to get noticed, males stand upright, puff up their necks, and making a call that sounds like a 'snort." They also use this display to defend their territory from competing breeding males.

The international team of researchers—from the UK, Kenya, Portugal, Spain and Brazil—found that high temperatures reduced this snort-call display behavior. If temperatures become too hot, birds may have to choose between mating and sheltering or resting to save their energy and protect themselves from the heat.

Published in the journal PLOS ONE, the findings show that during the mating season little bustard display behavior is significantly related to temperature, the time of the day—something referred to as circadian rhythms—and what stage of the mating season it is. The average temperature during the day also affects how much birds display and again as temperatures increase, display rates reduce.

In the study region of the Iberian Peninsula, average daily daytime (5:00—21:00 hours) temperatures varied between 10ºC and 31ºC. Snort-call display probability decreased substantially as temperature increased from 4 to 20ºC, stabilized from 20 to 30ºC, and decreased thereafter.

The researchers warn that the average display activity of the birds will continue to reduce by up to 10 percent for the temperature increases projected by 2100 in this region due to global warming.

Mishal Gudka, who led the research while at UEA's School of Biological Sciences, said: "This work has shown how global warming may affect important behavioral mechanisms using the mating system of a lekking grassland bird species as an example.

"For lekking birds and mammals undertaking these types of extravagant and energetic displays in a warming climate, less display activity could affect how females choose mates, providing an opportunity for genetically weaker males to mate more frequently. This in turn could lead to more failed copulation attempts, lower fertilization success and weaker offspring, reducing the overall population health.

"Unfortunately for little bustards, these potential consequences of reduced display combined with other existing threats such as loss of habitat, may push this endangered species towards local and regional extinctions."

The team used a novel method to understand how display behavior of little bustards is affected by temperature changes. Remote GPS/GSM accelerometer tracking devices were fitted to 17 wild male little bustards living at five sites in Spain and Portugal.

The researchers filmed the birds to observe their behavior at the same time as accelerometers recorded their position, and using this information they were able to determine the acceleration signature or pattern for snort-calling behavior.

Co-author Paul Dolman, Professor of Conservation Ecology at UEA's School of Environmental Sciences, said: "Many people are familiar with the impacts of global warming on wildlife through droughts, storms or wildfires as well as earlier migration with warming springs. But climate change affects species in many other subtle ways that may cause unexpected changes.

"Little bustards living in the Iberian Peninsula are already exposed to some of the highest temperatures within their species range. They are one of many bird and mammal species that have an extravagant, energetically demanding display ritual, meaning they are all susceptible to the same issue.

"Our findings highlight the need for further work to understand the mechanisms that underlie responses to climate change and to assess implications these changes may have at a population level."

The authors say the study is a replicable example of how tracking technology and acceleration data can be used to answer research questions with important conservation implications related to the impacts of climate change on a range of different animals.

The technology used in this work—GPS/GSM accelerometers—was developed by Movetech Telemetry, a scientific partnership involving UEA, the British Trust for Ornithology, CIBIO/InBIO at the University of Porto, and the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Lisbon, working together to develop animal tracking solutions.

phys.org/news/2019-09-global-harder-birds.html

Journal Reference:

Mishal Gudka et al. Feeling the heat: Elevated temperature affects male display activity of a lekking grassland bird, PLOS ONE (2019). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221999

Abstract

Most species-climate models relate range margins to long-term mean climate but lack mechanistic understanding of the ecological or demographic processes underlying the climate response. We examined the case of a climatically limited edge-of-range population of a medium-sized grassland bird, for which climate responses may involve a behavioural trade-off between temperature stress and reproduction. We hypothesised that temperature will be a limiting factor for the conspicuous, male snort-call display behaviour, and high temperatures would reduce the display activity of male birds. Using remote tracking technology with tri-axial accelerometers we classified and studied the display behaviour of 17 free-ranging male little bustards, Tetrax tetrax, at 5 sites in the Iberian Peninsula. Display behaviour was related to temperature using two classes of Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs) at different temporal resolutions. GAMMs showed that temperature, time of the day and Julian date explained variation in display behaviour within the day, with birds snort-calling significantly less during higher temperatures. We also showed that variation in daily snort-call activity was related to average daytime temperatures, with our model predicting an average decrease in daytime snort-call display activity of up to 10.4% for the temperature increases projected by 2100 in this region due to global warming. For lekking birds and mammals undertaking energetically-costly displays in a warming climate, reduced display behaviour could impact inter- and intra-sex mating behaviour interactions through sexual selection and mate choice mechanisms, with possible consequences on mating and reproductive success. The study provides a reproducible example for how accelerometer data can be used to answer research questions with important conservation inferences related to the impacts of climate change on a range of taxonomic groups.

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0221999