Post by OldGreenVulture on Jul 28, 2019 12:37:01 GMT

Eurasian Griffon Vulture

(Gyps fulvus)

Accipitriforme Order – Accipitridae Family

I had the pleasure to meet this splendid raptor in northern Spain and Extremadura.

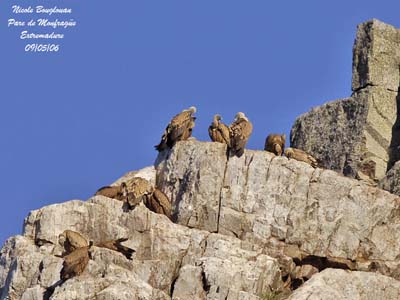

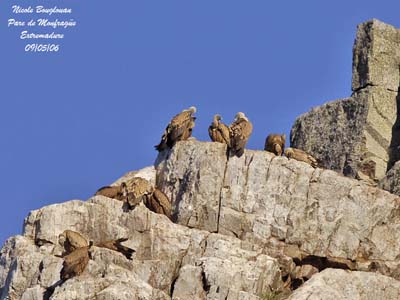

Inhabitant of the steep cliffs and rocky areas offering numerous cavities where it will nest, the Griffon Vulture haunts canyons and gorges with its large silhouette, gliding along the rock faces or soaring in group in the thermal currents, animating the blue of the sky. We only have to raise the eyes. Some of them circle in the air, others remain settled at the edge of the precipices. Gregarious birds, they are there, side by side, so similar that a succession of mirrors would not produce better illusion.

The Griffon Vulture is a large raptor. The upperparts are fulvous-brown, whereas the wings are rather dark with black primaries. The tail is short and black. The underparts show varied colours, from brown to reddish-brown. The long bare neck is covered with short creamy-white down. At the base, on the hind neck, the lack of plumage leaves a bare, purplish skin patch, similar to those which it sometimes voluntarily shows, located on its breast, and which are the reflection of its coolness or its excitation, passing from white to blue, and then to the red, according to its mood.

A ruff of white or pale brown feathers occurs around the neck and on the shoulders, often tinged red by the blood of the carcasses when it is feeding. The golden brown eyes liven this head up, equipped with powerful and pale hooked bill, made to tear to pieces the flesh. Immatures have the silhouette of the adults but are darker. They will need four years to obtain gradually the adult plumage.

The flight of the Griffon Vulture is a real show of virtuosity. It soars during long moments, moving scarcely the wings, in an almost unperceivable and measured way. Long and broad, they easily carry this clear-coloured body, contrasting with the much darker primary and secondary flight feathers. When the bird takes off from the ground or a steep wall, it performs slow and deep wing beats where the air rushes and raises the raptor. The landing is quite as beautiful to see with its approaches, the wings effectively slowing down the impact, and the legs kept away from the body, ready to touch the rock.

It detects its food while in flight. When it is settled, if it feels a light breeze, it takes advantage of it for flying away. If the sun is hot, it flies up into the sky until becoming an inaccessible point. There, it soars during hours, keeping an eye on the ground, but also on the other vultures of which the slightest change of attitude or flight can reveal a dead animal which will provide them food.

At this moment, it goes down and approaches with the other vultures, soaring over the area above the carrion. Then, they start continuous turns where each one observes the other without deciding to land. In fact, Egyptian Vultures and Corvidae often arrive first and eat the softer parts (tongue, eyes…). Then, the Griffon Vultures establish their hierarchy, coming from different places to gather in the same restricted zone. Some of them dive without landing, while others circle in the sky.

Finally, one of them lands far from the carcass, at about one hundred metres. The others follow very quickly. Then the fight for the hierarchy and the temporary domination on the others starts. After several disputes and other intimidation displays, a vulture bolder than the others goes directly to the carcass where already a dominating vulture opened the belly and started to eat the entrails. The last arrived are rejected by the dominating bird which faces them. They answer by stretching the neck and the head, erecting the ruff and shoulder’s feathers, and raise a leg towards their adversary, and sometimes, they jump towards him with open wings.

Although these attacks may appear violent, in spite of the large movements of wings, the pecks, jumps and whistles, the scene is simply ridiculous because the fight is not really serious. Only some marks left by the pecks on the neck and head are the witnesses of this pseudo confrontation.

In all cases, the dominating vulture cannot remain a long time at the first place, becoming vulnerable when it is feeding. Its strength to defend its position depends on its hunger. It is also known that when it hangs the head and keeps it hanging close to a carcass, no doubt that it is stimulating the gastric juices’ secretion. The degree of aggressiveness between the candidates for the feast is probably proportional to the secretion of these juices.

The scenes of necrophagous raptors feeding on a carcass are always a surprise for the observer, by seeing how the body of an animal can be reduced to the simple state of skin and bones in so little time!

The vultures leave this feast with head and neck covered with blood, as well as the moving ruff’s feathers. Sometimes, a vulture “enters” literally the carcass with many growls and eats the choice morsels! Then, if it finds water close by, it will go to wash by plunging into water, and will remain a long moment with open wings in the sun in order to dry its plumage.

The flight displays are an important period in the life of the Griffon Vulture. These flights occur in November-December, and are an unforgettable spectacle for that which gets the chance to see them. Even if these displays are not as beautiful as those of other raptors, they are the sign, by the short dives performed by both birds together, one chasing the other, of the beginning of the breeding season. These flights can occur throughout the year, and often gather other birds which join the previous.

At great height, a pair of Griffon Vultures slowly circles, with spread and stiff wings, close to each other or so well superimposed that they appear joined by an invisible wire. They fly thus in the sky, during short moments, following each other or flying in parallel, in a perfect harmony. These figures are named “flight in tandem”.

At this period, the vultures sleep where the future nest will be built. They nest in colonies, gathering with several pairs for nesting in the same area. Some colonies may contain a hundred of pairs. They are settled at variable altitude, sometimes up to 1600-1800 metres, but usually, they are found at about 1000-1300 metres.

The nest is built in a rock cavity, difficult to reach for human. It is made with medium-sized sticks of one or two centimetres in diameter, grasses, and finer twigs. It is not very in relation to the species. The nest differs from one vulture to another and even from a year to other in the same pair. It can make from 60 to 120 centimetres in diameter. The interior may be a depression well lined with grass, or only a simple hollow lined with feathers of other vultures, recovered in a nearby roost. The decoration is as changing as the owner’s character!

The female lays only one white egg, sometimes in January, but rather in February. Both mates take turns to incubate the single egg at least twice a day. The changes are very ceremonious, the raptors performing very spectacular slow and careful movements.

The incubation lasts from 52 to 60 days. The chick at hatching is very weak, with little down, and its weight is about 170 grams. The first days of their life are perilous, because they hatch in the mountain and at relatively high elevation. At this time of the year, the snow is abundant and many chicks do not resist to these hard conditions, in spite of the attention of their parents. The vulture likes the sun and hates the rain! That is why the parents brood the chick permanently and take regular turns.

At three weeks of age, the chick is entirely covered with dense down, and its weak first calls become more powerful. The parents feed it during the first days with a regurgitated pasty mass at regular intervals. At two months, it already weighs six kg.

At this age, the young has particular reaction if threatened or even seized. He vomits straight a large volume of half-digested meat. Fear reaction or aggressiveness? On the other hand, it does not make any defence against the intruders and does not peck, although faithful to the changes of mood of its parents, it may be sometimes aggressive. The feathers appear at about 60 days, and then, it becomes very quickly similar to the adults.

Four entire months are necessary before the young vulture finally flies freely. However, it is not completely independent, and the parents still feed it by regurgitation. The young often follows the adults searching for food, but they do not land close to the carcasses, preferring to return to the colony and remain together until their parents come back and feed them copiously.

After the breeding season, the vultures which breed in northern parts of the range or in high mountain, move southwards, but seldom on very long distances. The majority however seems to be sedentary.

Very gregarious species, the Griffon Vulture forms large bands, according to its numbers in the given areas. The roosts are often located at the same place that the nesting colony, or fairly near.

Currently, the Eurasian Griffon Vulture breeds in Spain and in the Grand Causse in the Massif Central (France). One finds it in primarily Mediterranean zones, breeding locally in Balkans, in southern Ukraine, on Albanian and Yugoslav coasts, reaching Asia by Turkey, and arriving in the Caucasus, Siberia, and as far as Western China. It is rare in northern Africa. The main European population is that of Spain.

Extremely protected, object of successful reintroductions in France, the species is however threatened by various dangers and the causes are numerous. First, the hard climate of high mountain causes mortality of the chicks; predation of the nests and removing of eggs and chicks; the cattle in the wild decreases and does not offer enough carcasses to the colonies; current medical measurements obliging to bury the dead animals deprive the raptors of these resources; the poisoned pieces of meat intended for the foxes and which are fatally absorbed by the vultures which die about it; the electric lines; lost pieces of lead shots…

The Griffon Vulture is also accused of attacks against living animals. The cattle be left to itself in our mountains is not protected. The females give birth without protection. Everyone knows that these raptors are fond of placenta and mother and young, in a state of weakness at this moment, become too easy preys.

It is also easy, in this case, to accuse the vulture which made the mistake of reproducing too well in our beautiful Pyrenees… that is the style today: one exterminates, one reintroduces, and one exterminates again because the experiment succeeded too well! Perhaps to keep an eye on the herds would be a simple and not very expensive way to protect the cattle, this was not what was done, not so long time ago? Even still now, the Eurasian Griffon Vulture is regarded as an animal of the devil, heralding of dead… Actually, it disturbs.

The installation of artificial “feeders” may supplement the scarcity of food, but vultures do not convert themselves into lazy, and continue to travel their usual areas of research, in order to clean the nature. And when food suddenly lacks, they reach other places where the human hand tries to repair the damage which it caused…

www.oiseaux-birds.com/article-griffon-vulture.html

(Gyps fulvus)

Accipitriforme Order – Accipitridae Family

I had the pleasure to meet this splendid raptor in northern Spain and Extremadura.

Inhabitant of the steep cliffs and rocky areas offering numerous cavities where it will nest, the Griffon Vulture haunts canyons and gorges with its large silhouette, gliding along the rock faces or soaring in group in the thermal currents, animating the blue of the sky. We only have to raise the eyes. Some of them circle in the air, others remain settled at the edge of the precipices. Gregarious birds, they are there, side by side, so similar that a succession of mirrors would not produce better illusion.

The Griffon Vulture is a large raptor. The upperparts are fulvous-brown, whereas the wings are rather dark with black primaries. The tail is short and black. The underparts show varied colours, from brown to reddish-brown. The long bare neck is covered with short creamy-white down. At the base, on the hind neck, the lack of plumage leaves a bare, purplish skin patch, similar to those which it sometimes voluntarily shows, located on its breast, and which are the reflection of its coolness or its excitation, passing from white to blue, and then to the red, according to its mood.

A ruff of white or pale brown feathers occurs around the neck and on the shoulders, often tinged red by the blood of the carcasses when it is feeding. The golden brown eyes liven this head up, equipped with powerful and pale hooked bill, made to tear to pieces the flesh. Immatures have the silhouette of the adults but are darker. They will need four years to obtain gradually the adult plumage.

The flight of the Griffon Vulture is a real show of virtuosity. It soars during long moments, moving scarcely the wings, in an almost unperceivable and measured way. Long and broad, they easily carry this clear-coloured body, contrasting with the much darker primary and secondary flight feathers. When the bird takes off from the ground or a steep wall, it performs slow and deep wing beats where the air rushes and raises the raptor. The landing is quite as beautiful to see with its approaches, the wings effectively slowing down the impact, and the legs kept away from the body, ready to touch the rock.

It detects its food while in flight. When it is settled, if it feels a light breeze, it takes advantage of it for flying away. If the sun is hot, it flies up into the sky until becoming an inaccessible point. There, it soars during hours, keeping an eye on the ground, but also on the other vultures of which the slightest change of attitude or flight can reveal a dead animal which will provide them food.

At this moment, it goes down and approaches with the other vultures, soaring over the area above the carrion. Then, they start continuous turns where each one observes the other without deciding to land. In fact, Egyptian Vultures and Corvidae often arrive first and eat the softer parts (tongue, eyes…). Then, the Griffon Vultures establish their hierarchy, coming from different places to gather in the same restricted zone. Some of them dive without landing, while others circle in the sky.

Finally, one of them lands far from the carcass, at about one hundred metres. The others follow very quickly. Then the fight for the hierarchy and the temporary domination on the others starts. After several disputes and other intimidation displays, a vulture bolder than the others goes directly to the carcass where already a dominating vulture opened the belly and started to eat the entrails. The last arrived are rejected by the dominating bird which faces them. They answer by stretching the neck and the head, erecting the ruff and shoulder’s feathers, and raise a leg towards their adversary, and sometimes, they jump towards him with open wings.

Although these attacks may appear violent, in spite of the large movements of wings, the pecks, jumps and whistles, the scene is simply ridiculous because the fight is not really serious. Only some marks left by the pecks on the neck and head are the witnesses of this pseudo confrontation.

In all cases, the dominating vulture cannot remain a long time at the first place, becoming vulnerable when it is feeding. Its strength to defend its position depends on its hunger. It is also known that when it hangs the head and keeps it hanging close to a carcass, no doubt that it is stimulating the gastric juices’ secretion. The degree of aggressiveness between the candidates for the feast is probably proportional to the secretion of these juices.

The scenes of necrophagous raptors feeding on a carcass are always a surprise for the observer, by seeing how the body of an animal can be reduced to the simple state of skin and bones in so little time!

The vultures leave this feast with head and neck covered with blood, as well as the moving ruff’s feathers. Sometimes, a vulture “enters” literally the carcass with many growls and eats the choice morsels! Then, if it finds water close by, it will go to wash by plunging into water, and will remain a long moment with open wings in the sun in order to dry its plumage.

The flight displays are an important period in the life of the Griffon Vulture. These flights occur in November-December, and are an unforgettable spectacle for that which gets the chance to see them. Even if these displays are not as beautiful as those of other raptors, they are the sign, by the short dives performed by both birds together, one chasing the other, of the beginning of the breeding season. These flights can occur throughout the year, and often gather other birds which join the previous.

At great height, a pair of Griffon Vultures slowly circles, with spread and stiff wings, close to each other or so well superimposed that they appear joined by an invisible wire. They fly thus in the sky, during short moments, following each other or flying in parallel, in a perfect harmony. These figures are named “flight in tandem”.

At this period, the vultures sleep where the future nest will be built. They nest in colonies, gathering with several pairs for nesting in the same area. Some colonies may contain a hundred of pairs. They are settled at variable altitude, sometimes up to 1600-1800 metres, but usually, they are found at about 1000-1300 metres.

The nest is built in a rock cavity, difficult to reach for human. It is made with medium-sized sticks of one or two centimetres in diameter, grasses, and finer twigs. It is not very in relation to the species. The nest differs from one vulture to another and even from a year to other in the same pair. It can make from 60 to 120 centimetres in diameter. The interior may be a depression well lined with grass, or only a simple hollow lined with feathers of other vultures, recovered in a nearby roost. The decoration is as changing as the owner’s character!

The female lays only one white egg, sometimes in January, but rather in February. Both mates take turns to incubate the single egg at least twice a day. The changes are very ceremonious, the raptors performing very spectacular slow and careful movements.

The incubation lasts from 52 to 60 days. The chick at hatching is very weak, with little down, and its weight is about 170 grams. The first days of their life are perilous, because they hatch in the mountain and at relatively high elevation. At this time of the year, the snow is abundant and many chicks do not resist to these hard conditions, in spite of the attention of their parents. The vulture likes the sun and hates the rain! That is why the parents brood the chick permanently and take regular turns.

At three weeks of age, the chick is entirely covered with dense down, and its weak first calls become more powerful. The parents feed it during the first days with a regurgitated pasty mass at regular intervals. At two months, it already weighs six kg.

At this age, the young has particular reaction if threatened or even seized. He vomits straight a large volume of half-digested meat. Fear reaction or aggressiveness? On the other hand, it does not make any defence against the intruders and does not peck, although faithful to the changes of mood of its parents, it may be sometimes aggressive. The feathers appear at about 60 days, and then, it becomes very quickly similar to the adults.

Four entire months are necessary before the young vulture finally flies freely. However, it is not completely independent, and the parents still feed it by regurgitation. The young often follows the adults searching for food, but they do not land close to the carcasses, preferring to return to the colony and remain together until their parents come back and feed them copiously.

After the breeding season, the vultures which breed in northern parts of the range or in high mountain, move southwards, but seldom on very long distances. The majority however seems to be sedentary.

Very gregarious species, the Griffon Vulture forms large bands, according to its numbers in the given areas. The roosts are often located at the same place that the nesting colony, or fairly near.

Currently, the Eurasian Griffon Vulture breeds in Spain and in the Grand Causse in the Massif Central (France). One finds it in primarily Mediterranean zones, breeding locally in Balkans, in southern Ukraine, on Albanian and Yugoslav coasts, reaching Asia by Turkey, and arriving in the Caucasus, Siberia, and as far as Western China. It is rare in northern Africa. The main European population is that of Spain.

Extremely protected, object of successful reintroductions in France, the species is however threatened by various dangers and the causes are numerous. First, the hard climate of high mountain causes mortality of the chicks; predation of the nests and removing of eggs and chicks; the cattle in the wild decreases and does not offer enough carcasses to the colonies; current medical measurements obliging to bury the dead animals deprive the raptors of these resources; the poisoned pieces of meat intended for the foxes and which are fatally absorbed by the vultures which die about it; the electric lines; lost pieces of lead shots…

The Griffon Vulture is also accused of attacks against living animals. The cattle be left to itself in our mountains is not protected. The females give birth without protection. Everyone knows that these raptors are fond of placenta and mother and young, in a state of weakness at this moment, become too easy preys.

It is also easy, in this case, to accuse the vulture which made the mistake of reproducing too well in our beautiful Pyrenees… that is the style today: one exterminates, one reintroduces, and one exterminates again because the experiment succeeded too well! Perhaps to keep an eye on the herds would be a simple and not very expensive way to protect the cattle, this was not what was done, not so long time ago? Even still now, the Eurasian Griffon Vulture is regarded as an animal of the devil, heralding of dead… Actually, it disturbs.

The installation of artificial “feeders” may supplement the scarcity of food, but vultures do not convert themselves into lazy, and continue to travel their usual areas of research, in order to clean the nature. And when food suddenly lacks, they reach other places where the human hand tries to repair the damage which it caused…

www.oiseaux-birds.com/article-griffon-vulture.html