Post by Eaglehawk on Jun 25, 2019 8:06:14 GMT

Tufted Puffin - Fratercula cirrhata

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

Genus: Fratercula

Species: Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas, 1769)

The tufted puffin (Fratercula cirrhata), also known as crested puffin, is a relatively abundant medium-sized pelagic seabird in the auk family (Alcidae) found throughout the North Pacific Ocean. It is one of three species of puffin that make up the genus Fratercula and is easily recognizable by its thick red bill and yellow tufts.

Description

Tufted puffins are around 35 cm (14 in) in length with a similar wingspan and weigh about three quarters of a kilogram (1.6 lbs), making them the largest of all the puffins. Birds from the western Pacific population are somewhat larger than those from the eastern Pacific, and male birds tend to be slightly larger than females.

They are mostly black with a white facial patch, and, typical of other puffin species, feature a very thick bill which is mostly red with some yellow and occasionally green markings. Their most distinctive feature and namesake are the yellow tufts (Latin: cirri) that appear annually on birds of both sexes as the summer reproductive season approaches. Their feet become bright red and their face also becomes bright white in the summer. During the feeding season, the tufts moult off and the plumage, beak and legs lose much of their lustre.

As among other alcids, the wings are relatively short, adapted for diving, underwater swimming and capturing prey rather than gliding, of which they are incapable. As a consequence, they have thick, dark myoglobin-rich breast muscles adapted for a fast and aerobically strenuous wing-beat cadence, which they can nonetheless maintain for long periods of time.

Juvenile tufted puffins resemble winter adults, but with a grey-brown breast shading to white on the belly, and a shallow, yellowish-brown bill. Overall, they resemble a horn-less and unmarked rhinoceros auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata).

Taxonomy

The tufted puffin was first described in 1769 by German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas. The scientific name Fratercula comes from the Medieval Latin fratercula, friar, a reference to the black and white plumage which resembles monastic robes. The specific name cirrhata is Latin for "curly-headed", from cirrus, a curl of hair. The vernacular name puffin – puffed in the sense of swollen – was originally applied to the fatty, salted meat of young birds of the unrelated species, the Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus), formerly known as the "Manks puffin". It is an Anglo-Norman word (Middle English pophyn or poffin) used for the cured carcasses. The Atlantic Puffin acquired the name at a much later stage, possibly because of its similar nesting habits, and it was formally applied to that species by Pennant in 1768. It was later extended to include the similar and related Pacific puffins.

Since it may be more closely related to the rhinoceros auklet than the other puffins, it is sometimes placed in the monotypic genus Lunda.

The juveniles, due to their similarity to C. monocerata, were initially mistaken for a distinct species of a monotypic genus, and named Sagmatorrhina lathami ("Latham's saddle-billed auk", from sagmata "saddle" and rhina "nose").

Distribution and habitat

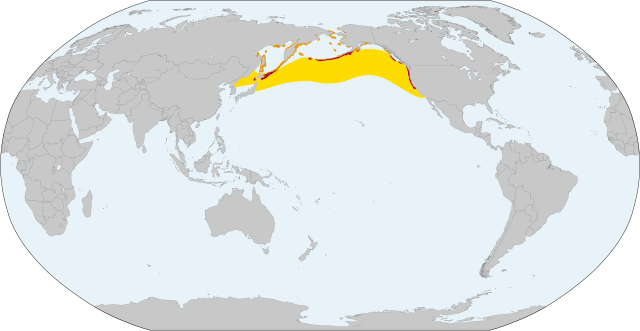

Tufted puffins form dense breeding colonies during the summer reproductive season from British Columbia, throughout southeastern Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands and throughout the Sea of Okhotsk. While they share some habitat with horned puffins (F. corniculata), the range of the tufted puffin is generally more eastern. They have been known to nest in small numbers as far south as the northern Channel Islands, off southern California. However, the last confirmed sighting at the Channel Islands occurred in 1997.

Tufted puffins typically select islands or cliffs that are relatively inaccessible to predators, close to productive waters, and high enough that they can take to the air successfully. Ideal habitat is steep but with a relatively soft soil substrate and grass for the creation of burrows.

During the winter feeding season, they spend their time almost exclusively at sea, extending their range throughout the North Pacific and south to Japan and California.

Distribution map of the tufted puffin

[align=left] extant (resident)[/align]

[align=left] extant (breeding visitor)[/align]

extant (winter visitor)

Behavior

Breeding

Breeding takes place on isolated islands: over 25,000 pairs have been recorded in a single colony off the coast of British Columbia. The nest is usually a simple burrow dug with the bill and feet, but sometimes a crevice between rocks is used instead. It is well-lined with vegetation and feathers. Courtship occurs through skypointing, strutting, and billing. A single egg is laid, usually in June, and incubated by both parents for about 45 days. Fledglings leave the nest at between 40 and 55 days.

Diet

Tufted puffins feed on a variety of fish and marine invertebrates, which they catch by diving from the surface. However, their diet varies greatly with age and location. Adult puffins largely depend on invertebrates, especially squid and krill. Nestlings at coastal colonies are fed primarily fish such as rockfish and sandlance, while nestlings at colonies closer to pelagic habitats are more dependent on invertebrates. Demersal fish are consumed in some quantity by most nestlings, suggesting that puffins feed to some extent on the ocean bottom.

Feeding areas can be located far offshore from the nesting areas. Puffins can store large quantities of small fish in their bills and carry them to their chicks.

Predators and threats

Tufted puffins are preyed upon by various avian raptors such as Snowy Owls, Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons, and mammals like the Arctic Fox. Foxes seem to prefer the puffin over other birds, making the bird a main target. Choosing inaccessible cliffs and entirely mammal-free islands protects them from terrestrial predators while laying eggs in burrows is effective in protecting them from egg-scavengers like gulls and ravens.

Relationship with humans

The Aleut and Ainu people of the North Pacific traditionally hunted tufted puffin for food and feathers. Skins were used to make tough parkas worn feather side in and the silky tufts were sewn into ornamental work. Currently, harvesting of tufted puffin is illegal or discouraged throughout its range.

The tufted puffin is a familiar bird on the coasts of the Russian Pacific coast, where it is known as toporok (Топорок) – meaning "small axe," a hint to the shape of the bill. Toporok is the namesake of one of its main breeding sites, Kamen Toporkov ("Tufted Puffin Rock") or Ostrov Toporkov ("Tufted Puffin Island"), an islet offshore Bering Island.

Conservation status in Puget Sound

Many rules and regulations have been set out to try to conserve fishes and shorebirds in Puget Sound. The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) of Washington State has created aquatic reserves surrounding Smith and Minor Islands. Over 36,000 acres (150 km2) of tidelands and seafloor habitat were included in the proposed aquatic reserve. Not only do these islands provide the necessary habitat for many seabirds such as tufted puffins and marine mammals, but this area also contains the largest kelp beds in all of Puget Sound. In addition, Protection Island reserve has also been off limits to the public to aid marine birds in breeding. Protection Island contains one of the last two nesting colonies of puffins in Puget Sound, and about 70% of the tufted puffin population nests on this island.

Climate change killing off Bering Sea puffins, say scientists

by Issam Ahmed

When an unusually large number of puffin carcasses began to wash ashore on Alaska's remote St Paul Island in the fall of 2016, the local tribal population grew alarmed.At first they suspected the seabirds might have avian flu—but labs on the mainland soon ruled out any disease, finding that the seabirds known for their brightly-colored beaks and thick tufts had instead starved to death.

In a new study published Wednesday researchers concluded the deaths, which occurred between October 2016 and February 2017, ran into the thousands—and were part of a growing number of mass die-offs recorded as climate change wreaks havoc on marine ecosystems.

The paper, which appeared in the journal PLOS ONE, found that although locals recovered only 350 carcasses, between 3,150 and 8,500 birds may have succumbed to starvation.

The majority were tufted puffins and the remainder were crested auklets.

The research team, which included scientists from the University of Washington and the Aleut Community of St Paul Island Ecosystem Conservation Office, said that from 2014 increased atmospheric temperatures and decreased winter sea ice led to declines in energy-rich prey species in the Bering Sea.

Tufted puffins breeding in the Bering Sea feed on small fish and marine invertebrates, which in turn eat ocean plankton.

"There was no fat there, the musculature was literally disintegrating," co-author Julia Parrish said of the birds, which washed up on the island, some 300 miles (480 kilometers) east of the mainland.

According to scientists, Alaska as a whole has been warming twice as fast as the global average, with temperatures earlier this year shattering records.

[align=left]Nineteen tufted puffins found on North Beach, St. Paul, Pribilof Islands, Alaska, on Oct. 19, 2016. Credit: Aleut Community of St Paul Island Ecosystem Conservation Office[/align]

"The puffins are one among several signals recorded that connect the physics of the system—how cold or warm it is— to the biology of the system," she told AFP.

"They just happen to be a very visible, graphic signal because it's really hard to avoid hundreds or thousands of birds dying and washing up at your feet."

'Ran out of gas'

The researchers also realized that most of the dead birds had begun molting, the process by which they lose their feathers and gain new plumage. During this time their ability to dive and hunt for food is diminished.

By the time they began molting, the birds should already have migrated to resource-rich waters to the west and south. The energy-intense nature of the transformation appears to have contributed to their starving.

"So all of those things indicated that they did not have enough to eat, they were late in migrating, they literally ran out of gas," said Parrish.

The paper noted "multi-year stanzas of warm conditions," such as those seen from 2001 to 2005 and 2014 to the present, may be particularly detrimental to seabirds, whose future viability will depend on their resilience to these changes.

"I'm tremendously worried," said Parrish. "If I had only seen this puffin die-off I might be a bit more circumspect, but this is one of about six die-offs since about 2014, 15" that collectively account for the deaths of millions of birds.

"Not just the Bering Sea, the whole north Pacific is changing," she added. "I think the ecosystem is screaming at us and we ignore it at our peril."

Journal Reference:

Jones T, Divine LM, Renner H, Knowles S, Lefebvre KA, Burgess HK, et al. (2019) Unusual mortality of Tufted puffins (Fratercula cirrhata) in the eastern Bering Sea. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0216532. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216532

Abstract

Mass mortality events are increasing in frequency and magnitude, potentially linked with ongoing climate change. In October 2016 through January 2017, St. Paul Island, Bering Sea, Alaska, experienced a mortality event of alcids (family: Alcidae), with over 350 carcasses recovered. Almost three-quarters of the carcasses were unscavenged, a rate much higher than in baseline surveys (17%), suggesting ongoing deposition and elevated mortality around St Paul over a 2–3 month period. Based on the observation that carcasses were not observed on the neighboring island of St. George, we bounded the at-sea distribution of moribund birds, and estimated all species mortality at 3,150 to 8,800 birds. The event was particularly anomalous given the late fall/winter timing when low numbers of beached birds are typical. In addition, the predominance of Tufted puffins (Fratercula cirrhata, 79% of carcass finds) and Crested auklets (Aethia cristatella, 11% of carcass finds) was unusual, as these species are nearly absent from long-term baseline surveys. Collected specimens were severely emaciated, suggesting starvation as the ultimate cause of mortality. The majority (95%, N = 245) of Tufted puffins were adults regrowing flight feathers, indicating a potential contribution of molt stress. Immediately prior to this event, shifts in zooplankton community composition and in forage fish distribution and energy density were documented in the eastern Bering Sea following a period of elevated sea surface temperatures, evidence cumulatively suggestive of a bottom-up shift in seabird prey availability. We posit that shifts in prey composition and/or distribution, combined with the onset of molt, resulted in this mortality event.

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0216532

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Alcidae

Genus: Fratercula

Species: Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas, 1769)

The tufted puffin (Fratercula cirrhata), also known as crested puffin, is a relatively abundant medium-sized pelagic seabird in the auk family (Alcidae) found throughout the North Pacific Ocean. It is one of three species of puffin that make up the genus Fratercula and is easily recognizable by its thick red bill and yellow tufts.

Description

Tufted puffins are around 35 cm (14 in) in length with a similar wingspan and weigh about three quarters of a kilogram (1.6 lbs), making them the largest of all the puffins. Birds from the western Pacific population are somewhat larger than those from the eastern Pacific, and male birds tend to be slightly larger than females.

They are mostly black with a white facial patch, and, typical of other puffin species, feature a very thick bill which is mostly red with some yellow and occasionally green markings. Their most distinctive feature and namesake are the yellow tufts (Latin: cirri) that appear annually on birds of both sexes as the summer reproductive season approaches. Their feet become bright red and their face also becomes bright white in the summer. During the feeding season, the tufts moult off and the plumage, beak and legs lose much of their lustre.

As among other alcids, the wings are relatively short, adapted for diving, underwater swimming and capturing prey rather than gliding, of which they are incapable. As a consequence, they have thick, dark myoglobin-rich breast muscles adapted for a fast and aerobically strenuous wing-beat cadence, which they can nonetheless maintain for long periods of time.

Juvenile tufted puffins resemble winter adults, but with a grey-brown breast shading to white on the belly, and a shallow, yellowish-brown bill. Overall, they resemble a horn-less and unmarked rhinoceros auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata).

Taxonomy

The tufted puffin was first described in 1769 by German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas. The scientific name Fratercula comes from the Medieval Latin fratercula, friar, a reference to the black and white plumage which resembles monastic robes. The specific name cirrhata is Latin for "curly-headed", from cirrus, a curl of hair. The vernacular name puffin – puffed in the sense of swollen – was originally applied to the fatty, salted meat of young birds of the unrelated species, the Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus), formerly known as the "Manks puffin". It is an Anglo-Norman word (Middle English pophyn or poffin) used for the cured carcasses. The Atlantic Puffin acquired the name at a much later stage, possibly because of its similar nesting habits, and it was formally applied to that species by Pennant in 1768. It was later extended to include the similar and related Pacific puffins.

Since it may be more closely related to the rhinoceros auklet than the other puffins, it is sometimes placed in the monotypic genus Lunda.

The juveniles, due to their similarity to C. monocerata, were initially mistaken for a distinct species of a monotypic genus, and named Sagmatorrhina lathami ("Latham's saddle-billed auk", from sagmata "saddle" and rhina "nose").

Distribution and habitat

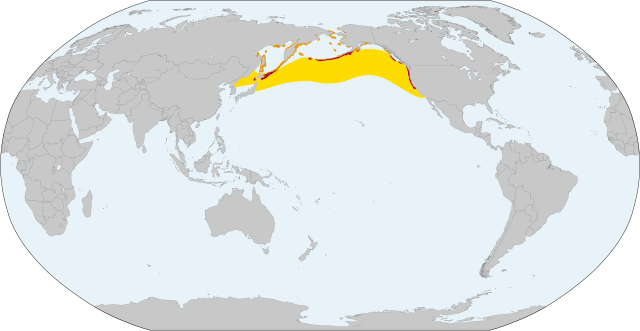

Tufted puffins form dense breeding colonies during the summer reproductive season from British Columbia, throughout southeastern Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands and throughout the Sea of Okhotsk. While they share some habitat with horned puffins (F. corniculata), the range of the tufted puffin is generally more eastern. They have been known to nest in small numbers as far south as the northern Channel Islands, off southern California. However, the last confirmed sighting at the Channel Islands occurred in 1997.

Tufted puffins typically select islands or cliffs that are relatively inaccessible to predators, close to productive waters, and high enough that they can take to the air successfully. Ideal habitat is steep but with a relatively soft soil substrate and grass for the creation of burrows.

During the winter feeding season, they spend their time almost exclusively at sea, extending their range throughout the North Pacific and south to Japan and California.

Distribution map of the tufted puffin

[align=left] extant (resident)[/align]

[align=left] extant (breeding visitor)[/align]

extant (winter visitor)

Behavior

Breeding

Breeding takes place on isolated islands: over 25,000 pairs have been recorded in a single colony off the coast of British Columbia. The nest is usually a simple burrow dug with the bill and feet, but sometimes a crevice between rocks is used instead. It is well-lined with vegetation and feathers. Courtship occurs through skypointing, strutting, and billing. A single egg is laid, usually in June, and incubated by both parents for about 45 days. Fledglings leave the nest at between 40 and 55 days.

Diet

Tufted puffins feed on a variety of fish and marine invertebrates, which they catch by diving from the surface. However, their diet varies greatly with age and location. Adult puffins largely depend on invertebrates, especially squid and krill. Nestlings at coastal colonies are fed primarily fish such as rockfish and sandlance, while nestlings at colonies closer to pelagic habitats are more dependent on invertebrates. Demersal fish are consumed in some quantity by most nestlings, suggesting that puffins feed to some extent on the ocean bottom.

Feeding areas can be located far offshore from the nesting areas. Puffins can store large quantities of small fish in their bills and carry them to their chicks.

Predators and threats

Tufted puffins are preyed upon by various avian raptors such as Snowy Owls, Bald Eagles and Peregrine Falcons, and mammals like the Arctic Fox. Foxes seem to prefer the puffin over other birds, making the bird a main target. Choosing inaccessible cliffs and entirely mammal-free islands protects them from terrestrial predators while laying eggs in burrows is effective in protecting them from egg-scavengers like gulls and ravens.

Relationship with humans

The Aleut and Ainu people of the North Pacific traditionally hunted tufted puffin for food and feathers. Skins were used to make tough parkas worn feather side in and the silky tufts were sewn into ornamental work. Currently, harvesting of tufted puffin is illegal or discouraged throughout its range.

The tufted puffin is a familiar bird on the coasts of the Russian Pacific coast, where it is known as toporok (Топорок) – meaning "small axe," a hint to the shape of the bill. Toporok is the namesake of one of its main breeding sites, Kamen Toporkov ("Tufted Puffin Rock") or Ostrov Toporkov ("Tufted Puffin Island"), an islet offshore Bering Island.

Conservation status in Puget Sound

Many rules and regulations have been set out to try to conserve fishes and shorebirds in Puget Sound. The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) of Washington State has created aquatic reserves surrounding Smith and Minor Islands. Over 36,000 acres (150 km2) of tidelands and seafloor habitat were included in the proposed aquatic reserve. Not only do these islands provide the necessary habitat for many seabirds such as tufted puffins and marine mammals, but this area also contains the largest kelp beds in all of Puget Sound. In addition, Protection Island reserve has also been off limits to the public to aid marine birds in breeding. Protection Island contains one of the last two nesting colonies of puffins in Puget Sound, and about 70% of the tufted puffin population nests on this island.

Climate change killing off Bering Sea puffins, say scientists

by Issam Ahmed

When an unusually large number of puffin carcasses began to wash ashore on Alaska's remote St Paul Island in the fall of 2016, the local tribal population grew alarmed.At first they suspected the seabirds might have avian flu—but labs on the mainland soon ruled out any disease, finding that the seabirds known for their brightly-colored beaks and thick tufts had instead starved to death.

In a new study published Wednesday researchers concluded the deaths, which occurred between October 2016 and February 2017, ran into the thousands—and were part of a growing number of mass die-offs recorded as climate change wreaks havoc on marine ecosystems.

The paper, which appeared in the journal PLOS ONE, found that although locals recovered only 350 carcasses, between 3,150 and 8,500 birds may have succumbed to starvation.

The majority were tufted puffins and the remainder were crested auklets.

The research team, which included scientists from the University of Washington and the Aleut Community of St Paul Island Ecosystem Conservation Office, said that from 2014 increased atmospheric temperatures and decreased winter sea ice led to declines in energy-rich prey species in the Bering Sea.

Tufted puffins breeding in the Bering Sea feed on small fish and marine invertebrates, which in turn eat ocean plankton.

"There was no fat there, the musculature was literally disintegrating," co-author Julia Parrish said of the birds, which washed up on the island, some 300 miles (480 kilometers) east of the mainland.

According to scientists, Alaska as a whole has been warming twice as fast as the global average, with temperatures earlier this year shattering records.

[align=left]Nineteen tufted puffins found on North Beach, St. Paul, Pribilof Islands, Alaska, on Oct. 19, 2016. Credit: Aleut Community of St Paul Island Ecosystem Conservation Office[/align]

"The puffins are one among several signals recorded that connect the physics of the system—how cold or warm it is— to the biology of the system," she told AFP.

"They just happen to be a very visible, graphic signal because it's really hard to avoid hundreds or thousands of birds dying and washing up at your feet."

'Ran out of gas'

The researchers also realized that most of the dead birds had begun molting, the process by which they lose their feathers and gain new plumage. During this time their ability to dive and hunt for food is diminished.

By the time they began molting, the birds should already have migrated to resource-rich waters to the west and south. The energy-intense nature of the transformation appears to have contributed to their starving.

"So all of those things indicated that they did not have enough to eat, they were late in migrating, they literally ran out of gas," said Parrish.

The paper noted "multi-year stanzas of warm conditions," such as those seen from 2001 to 2005 and 2014 to the present, may be particularly detrimental to seabirds, whose future viability will depend on their resilience to these changes.

"I'm tremendously worried," said Parrish. "If I had only seen this puffin die-off I might be a bit more circumspect, but this is one of about six die-offs since about 2014, 15" that collectively account for the deaths of millions of birds.

"Not just the Bering Sea, the whole north Pacific is changing," she added. "I think the ecosystem is screaming at us and we ignore it at our peril."

Journal Reference:

Jones T, Divine LM, Renner H, Knowles S, Lefebvre KA, Burgess HK, et al. (2019) Unusual mortality of Tufted puffins (Fratercula cirrhata) in the eastern Bering Sea. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0216532. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216532

Abstract

Mass mortality events are increasing in frequency and magnitude, potentially linked with ongoing climate change. In October 2016 through January 2017, St. Paul Island, Bering Sea, Alaska, experienced a mortality event of alcids (family: Alcidae), with over 350 carcasses recovered. Almost three-quarters of the carcasses were unscavenged, a rate much higher than in baseline surveys (17%), suggesting ongoing deposition and elevated mortality around St Paul over a 2–3 month period. Based on the observation that carcasses were not observed on the neighboring island of St. George, we bounded the at-sea distribution of moribund birds, and estimated all species mortality at 3,150 to 8,800 birds. The event was particularly anomalous given the late fall/winter timing when low numbers of beached birds are typical. In addition, the predominance of Tufted puffins (Fratercula cirrhata, 79% of carcass finds) and Crested auklets (Aethia cristatella, 11% of carcass finds) was unusual, as these species are nearly absent from long-term baseline surveys. Collected specimens were severely emaciated, suggesting starvation as the ultimate cause of mortality. The majority (95%, N = 245) of Tufted puffins were adults regrowing flight feathers, indicating a potential contribution of molt stress. Immediately prior to this event, shifts in zooplankton community composition and in forage fish distribution and energy density were documented in the eastern Bering Sea following a period of elevated sea surface temperatures, evidence cumulatively suggestive of a bottom-up shift in seabird prey availability. We posit that shifts in prey composition and/or distribution, combined with the onset of molt, resulted in this mortality event.

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0216532